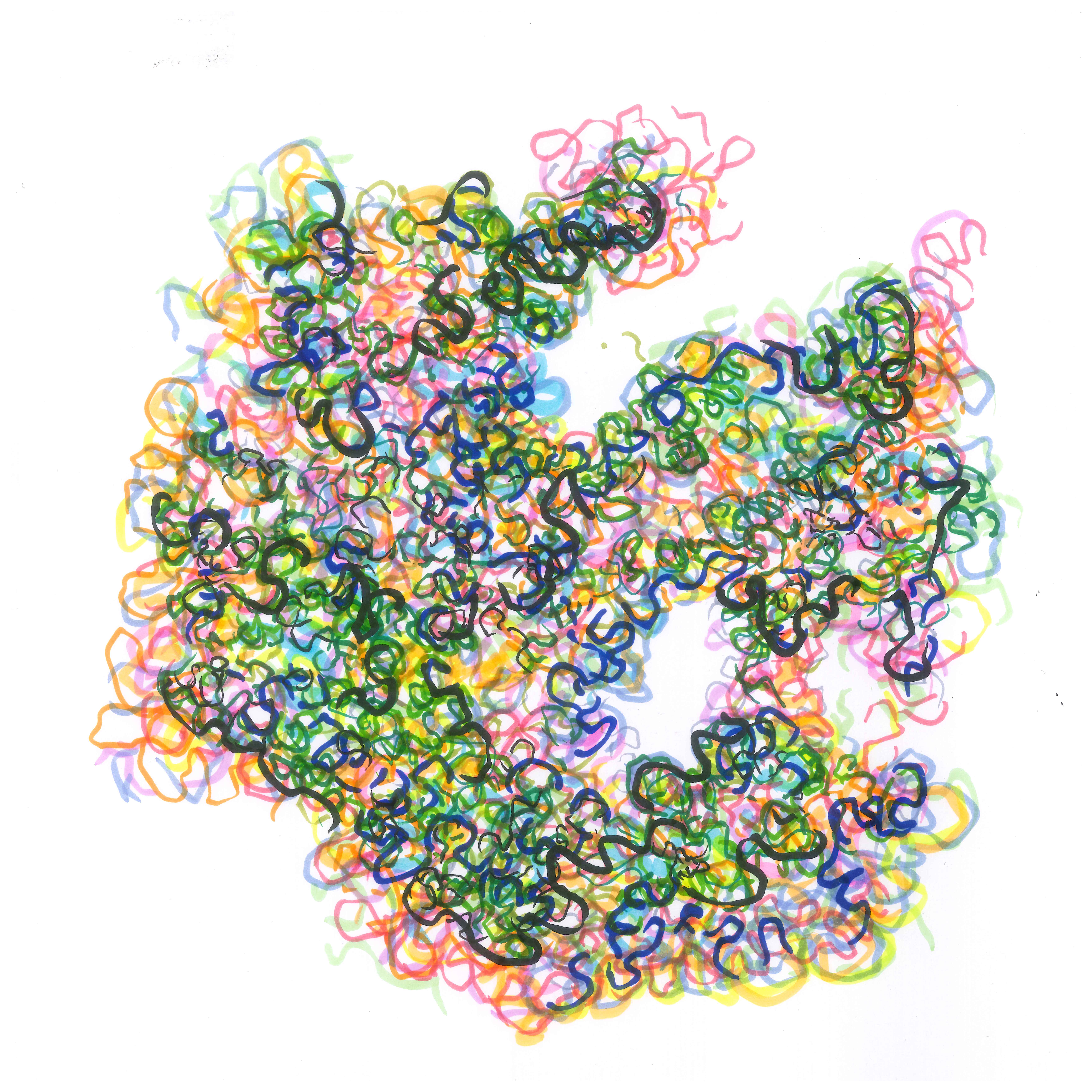

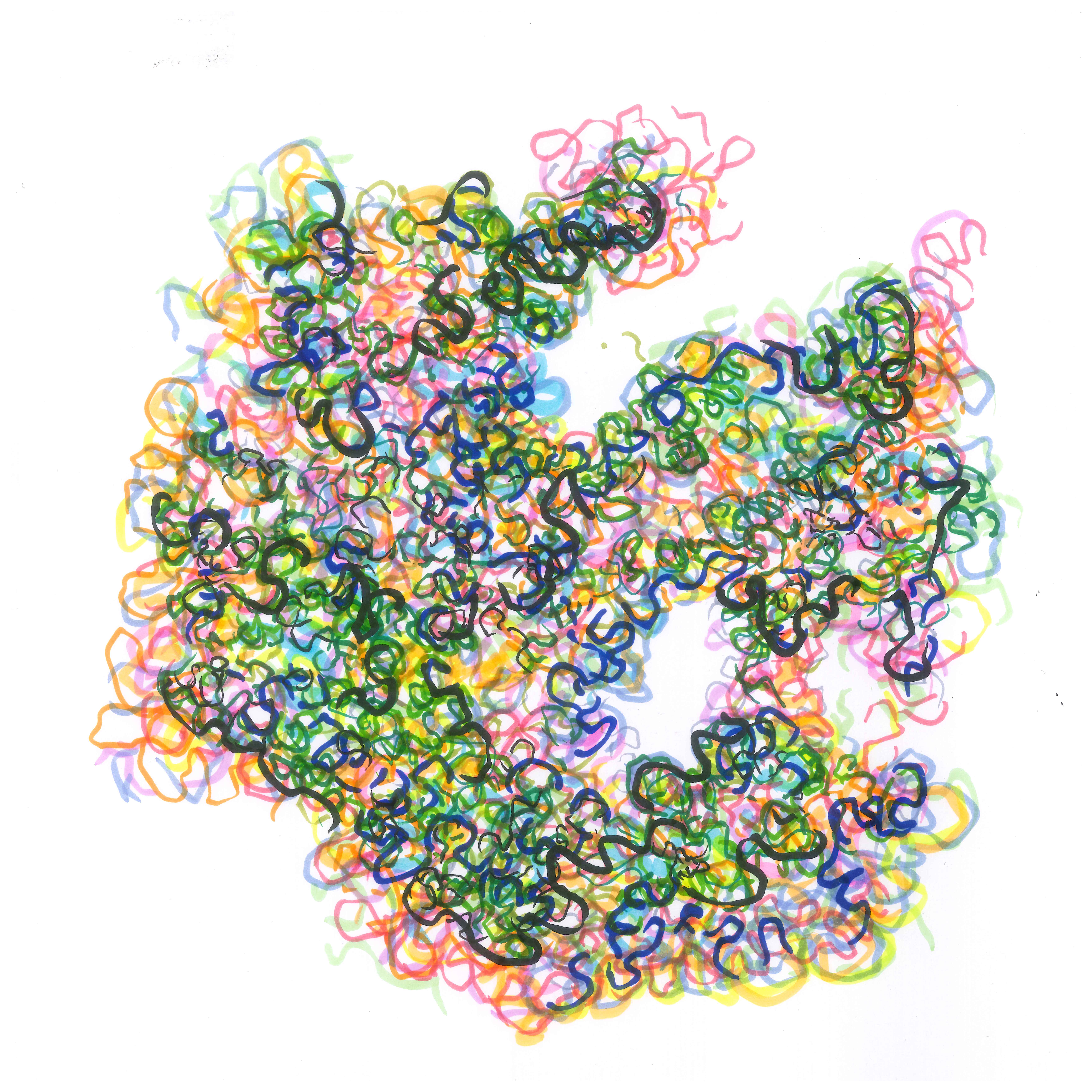

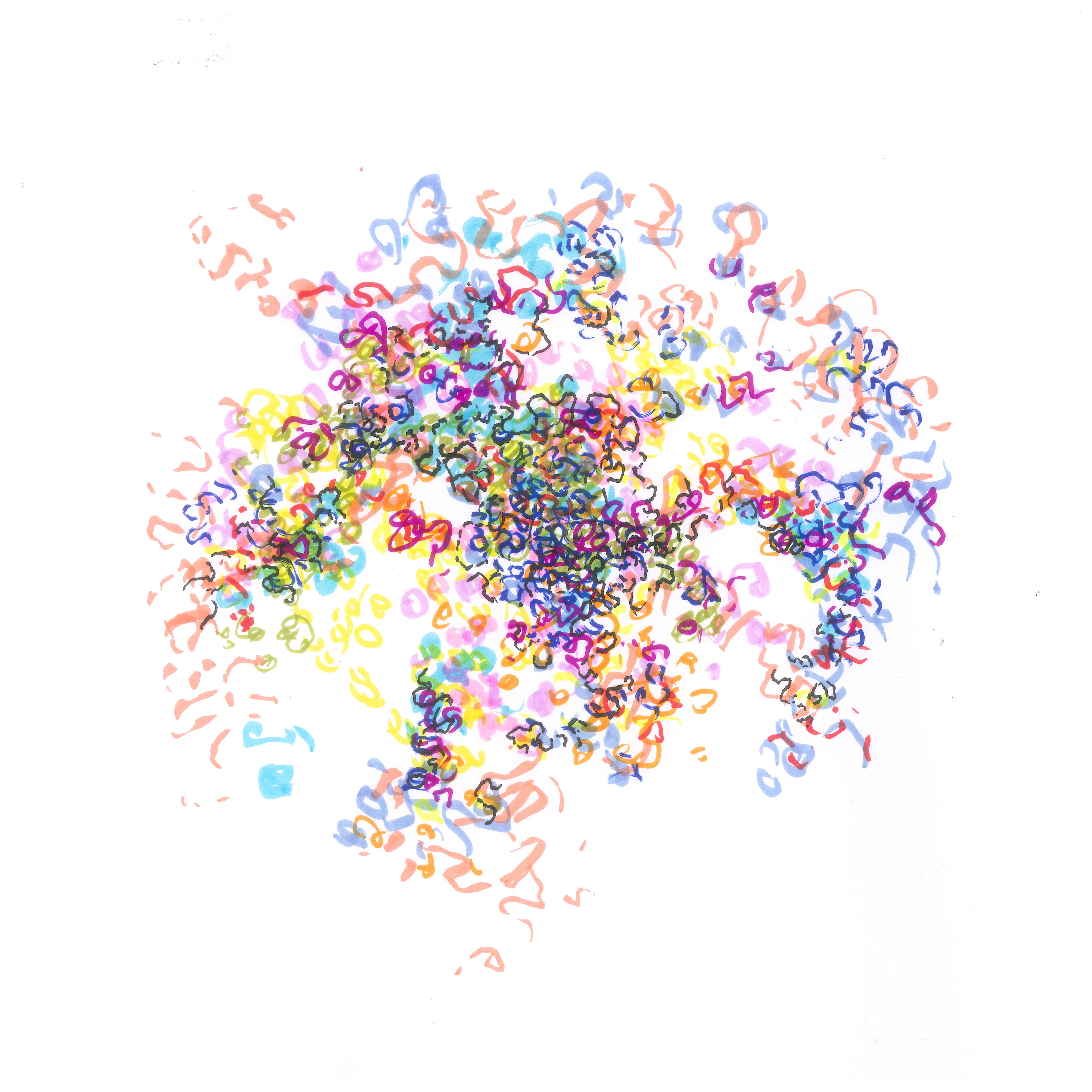

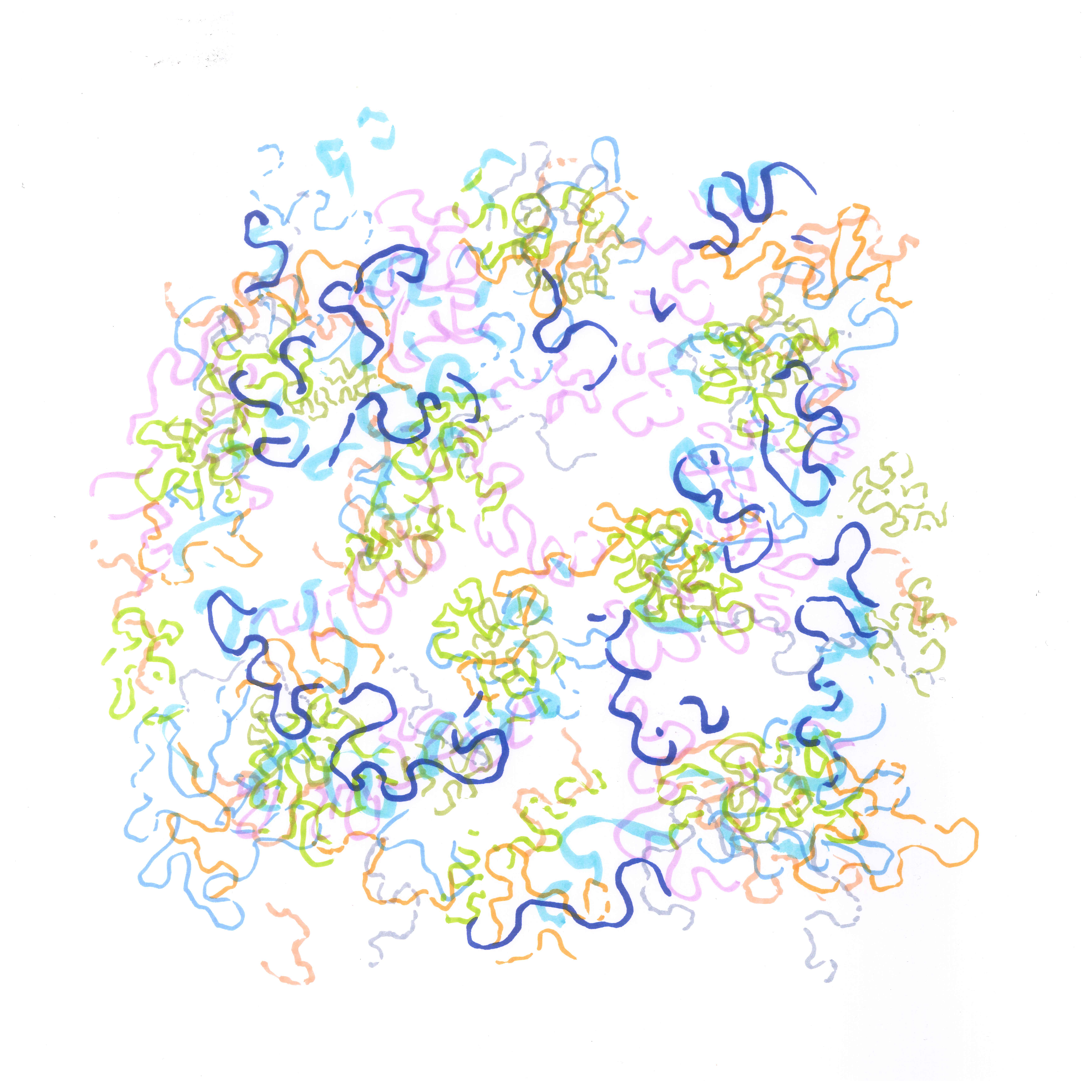

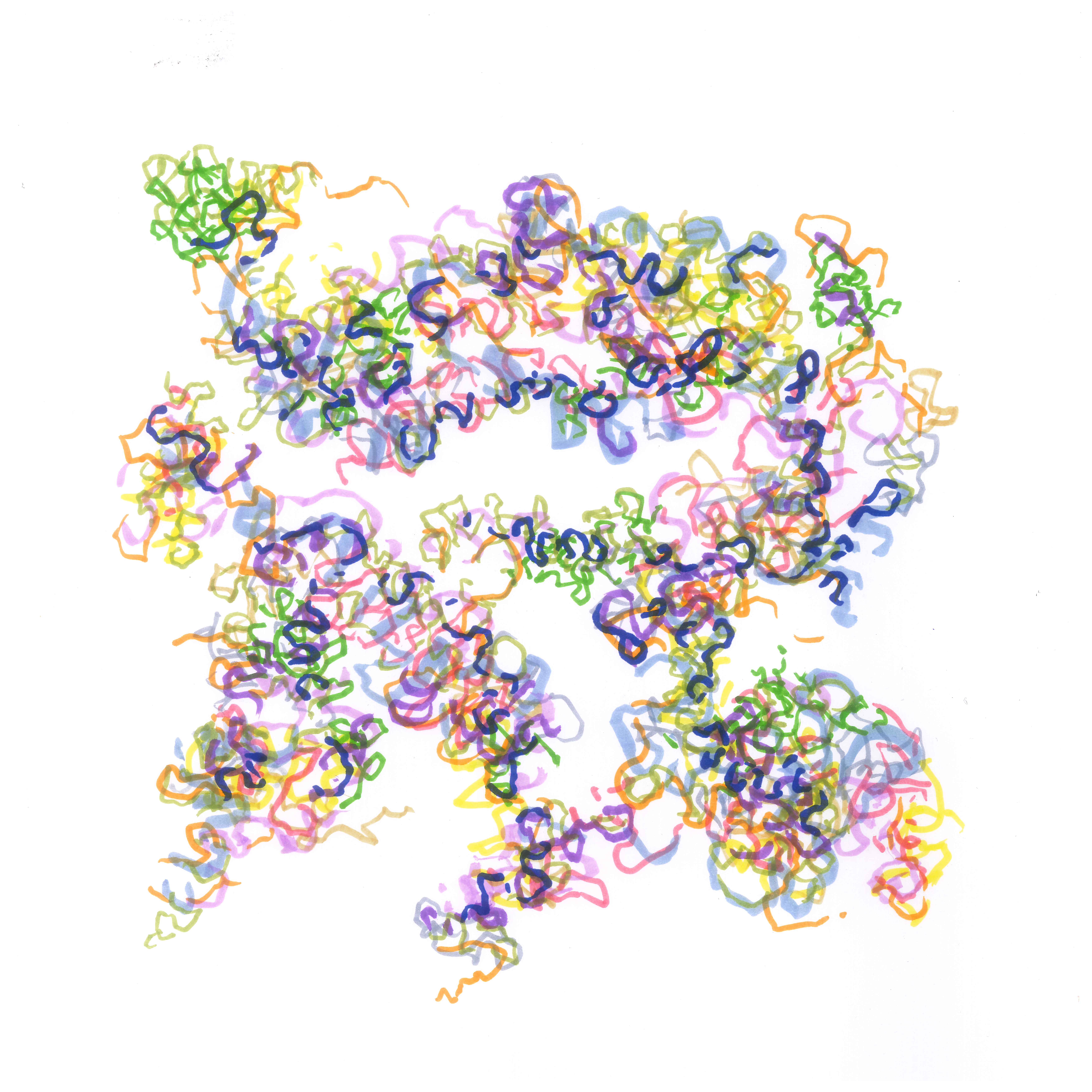

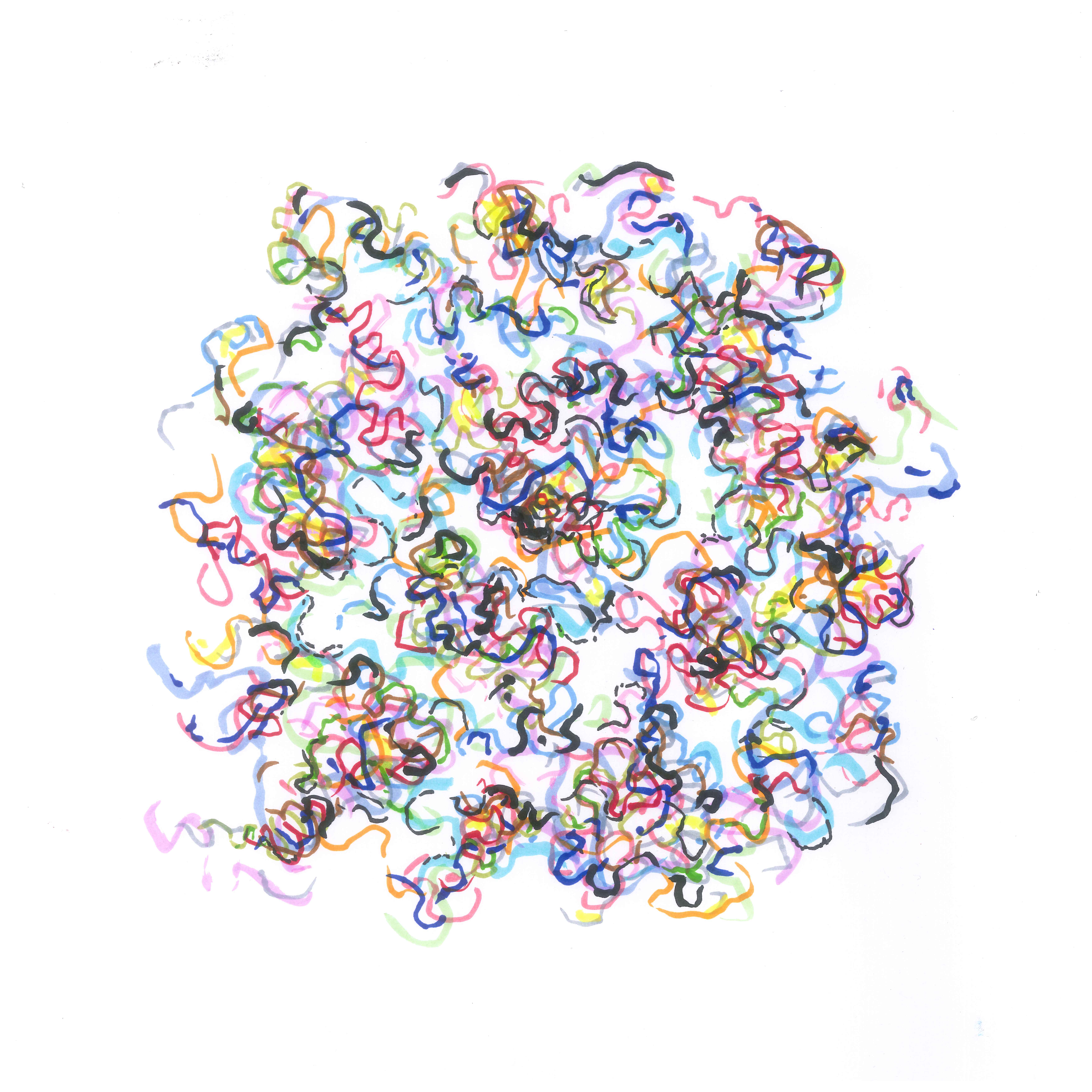

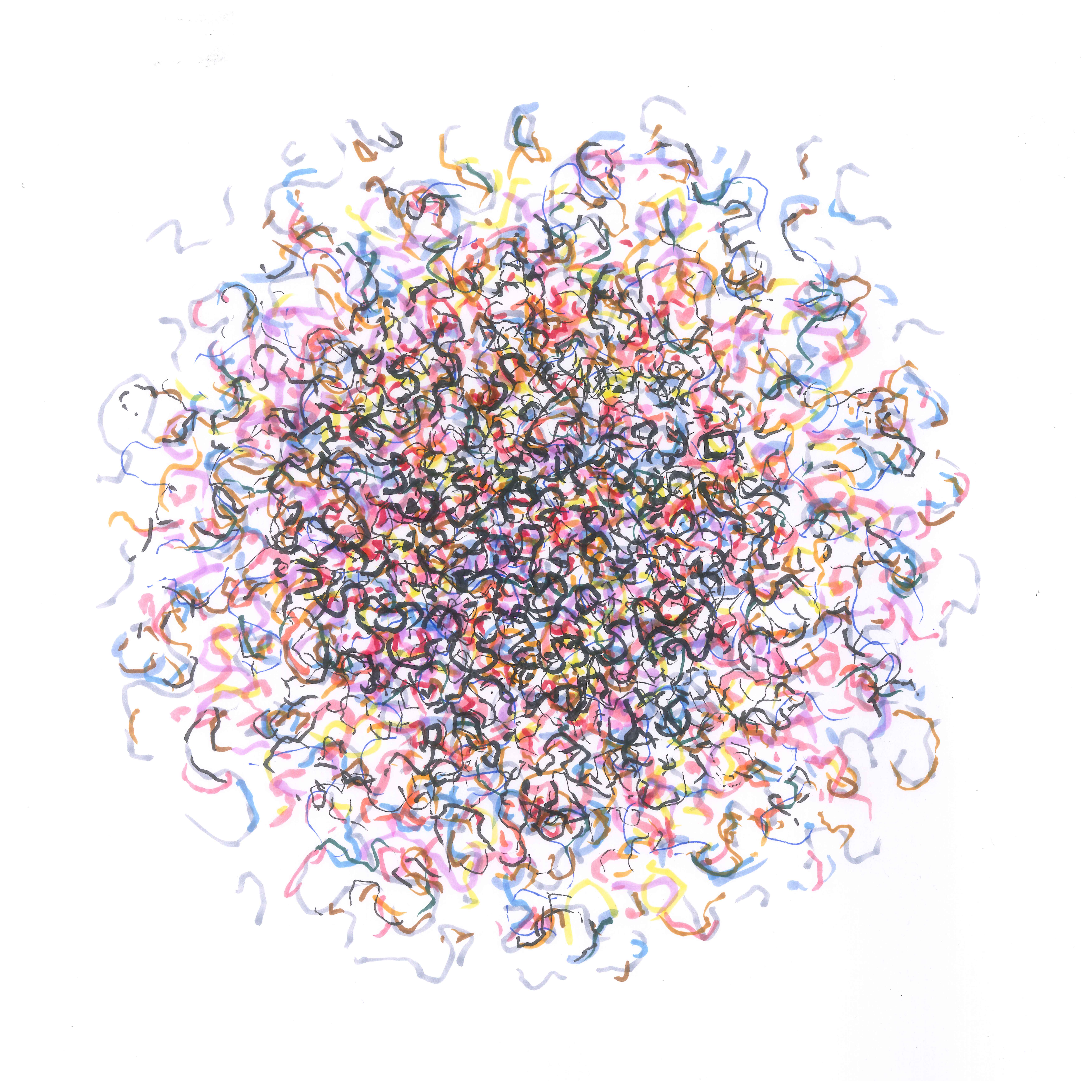

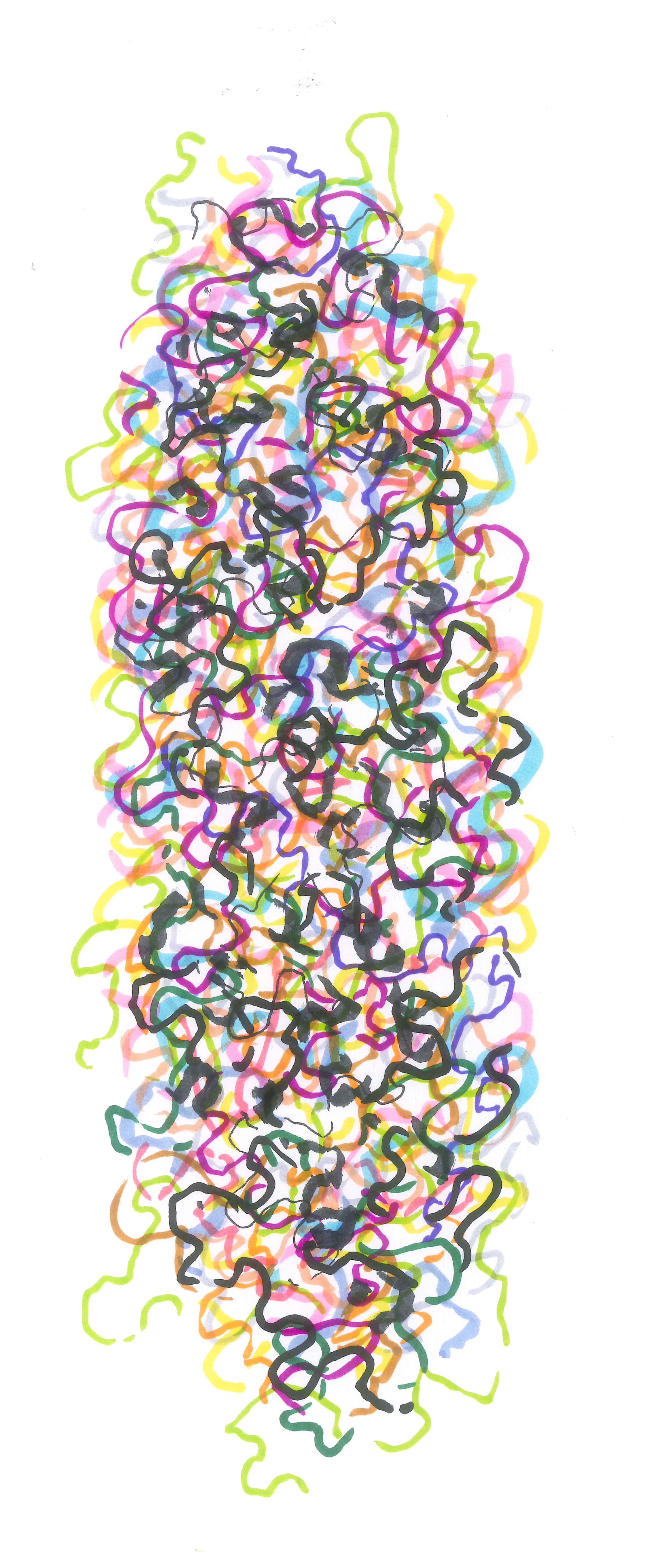

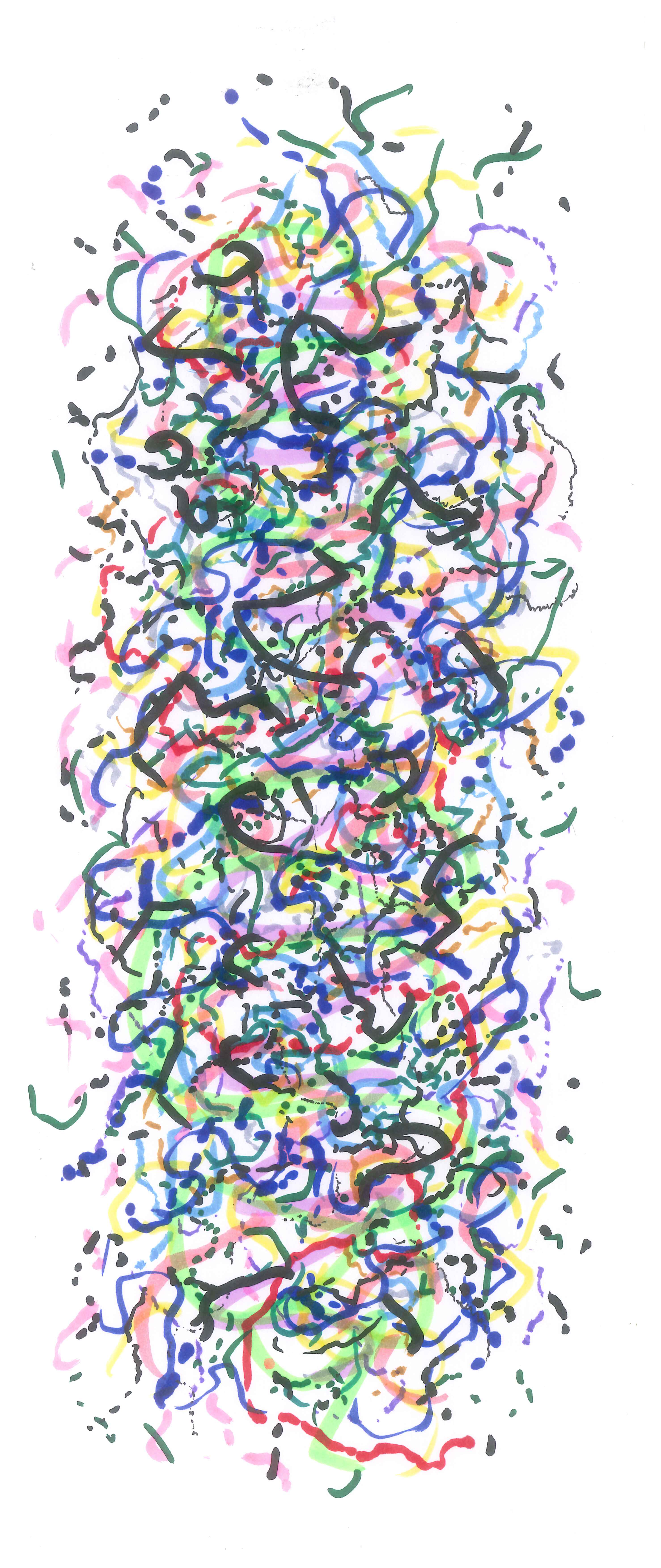

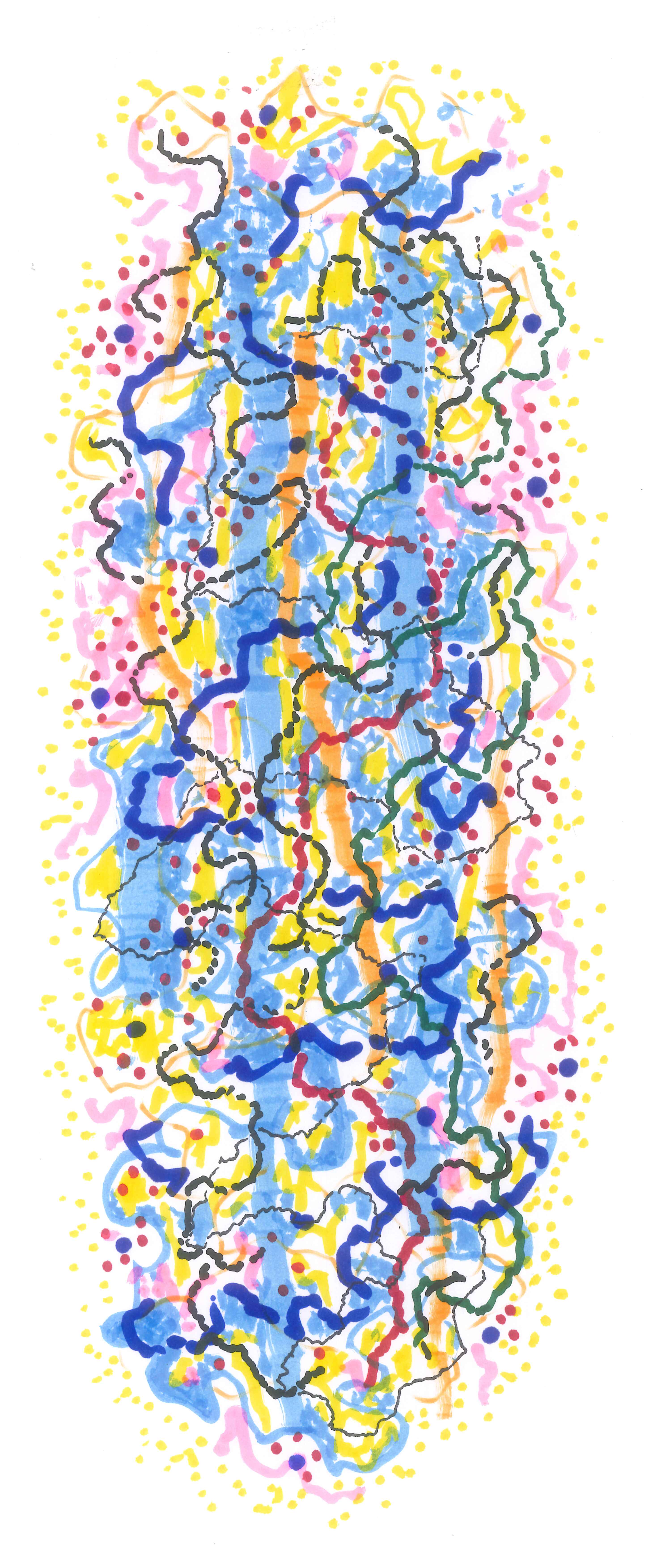

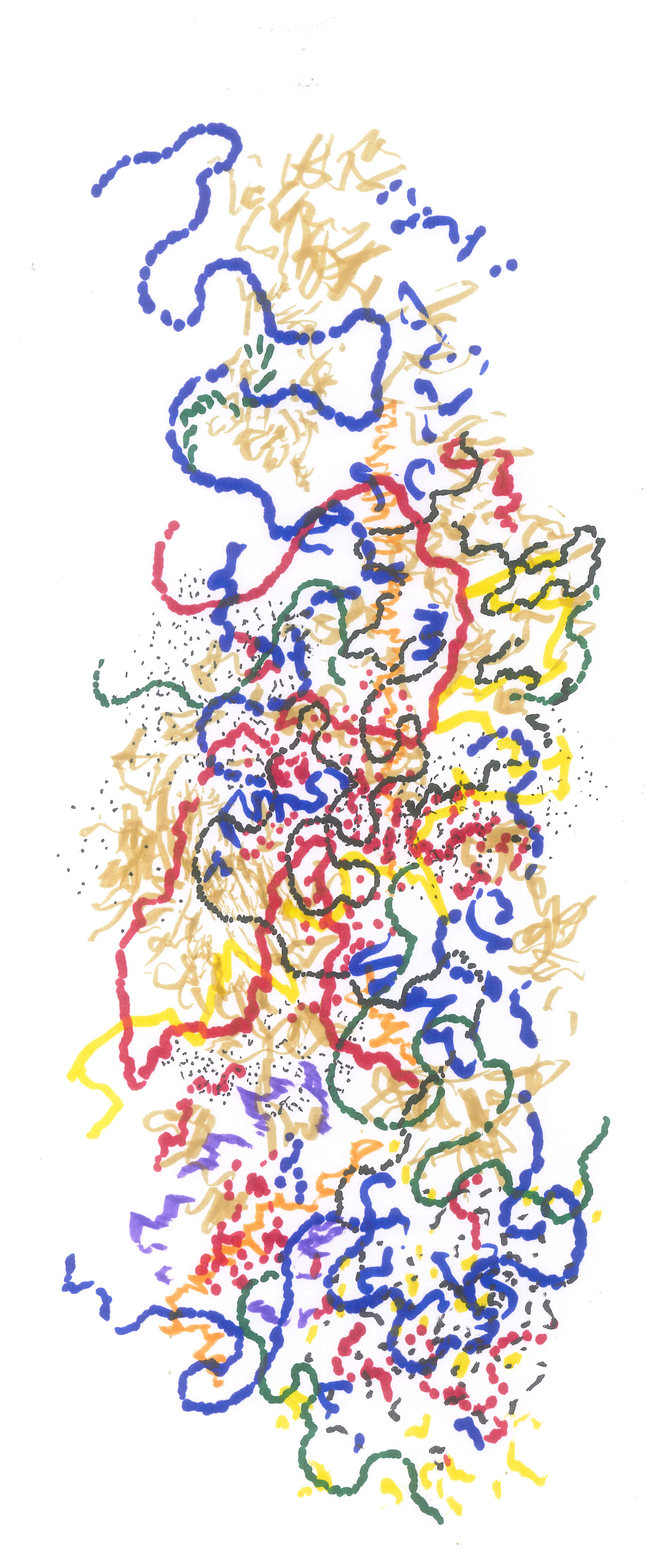

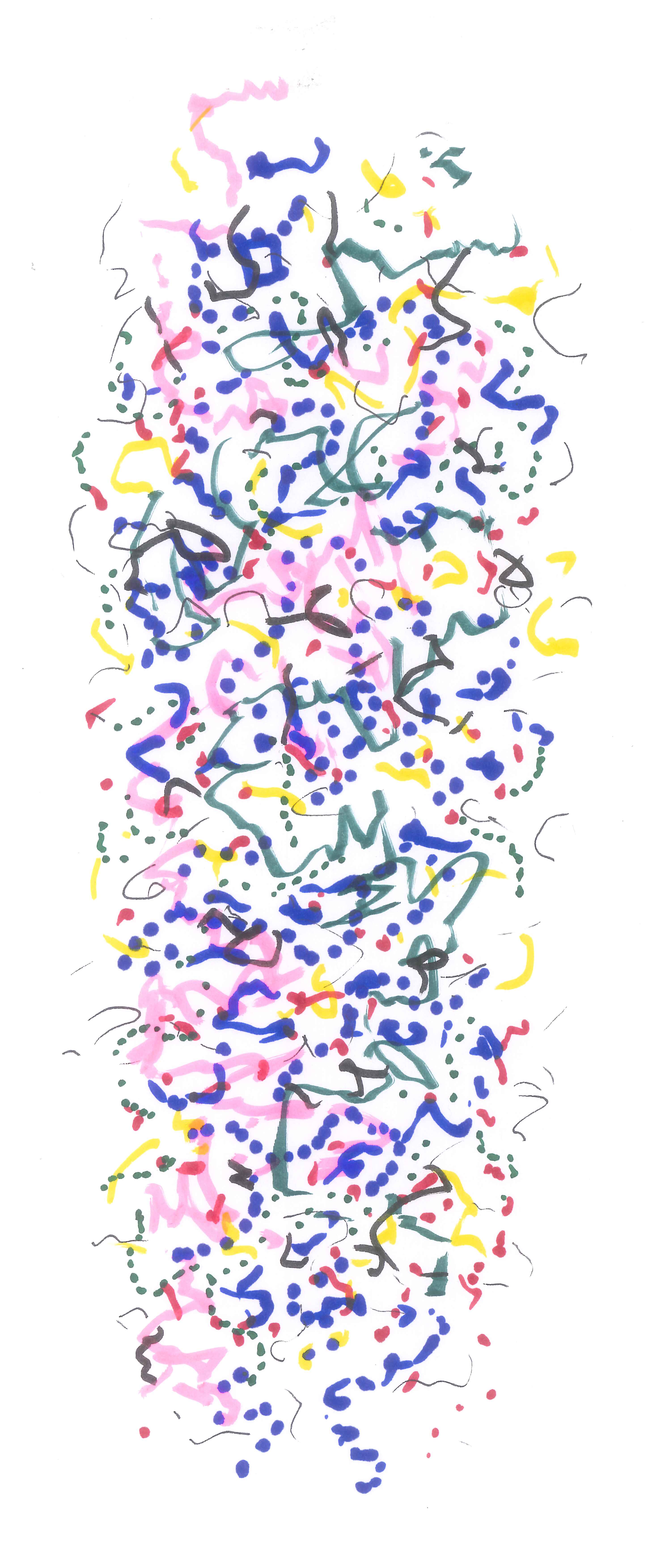

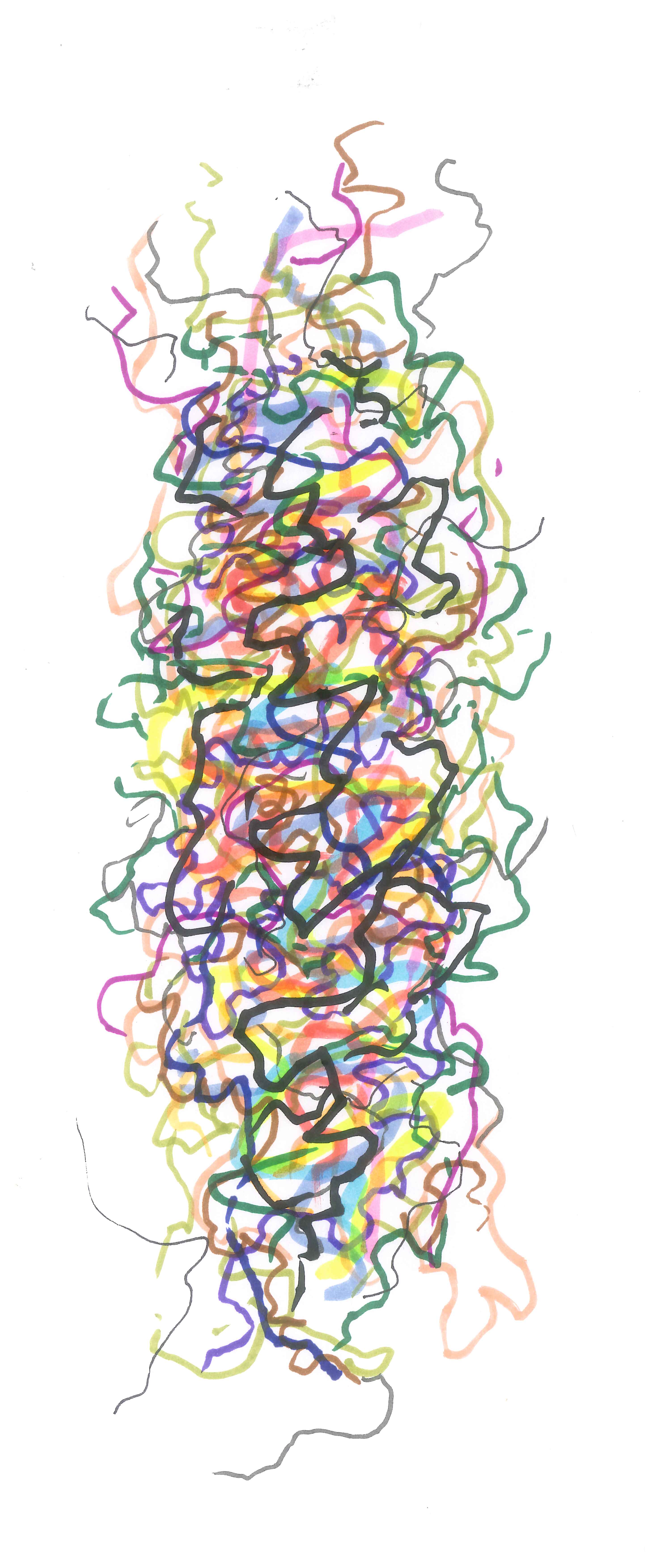

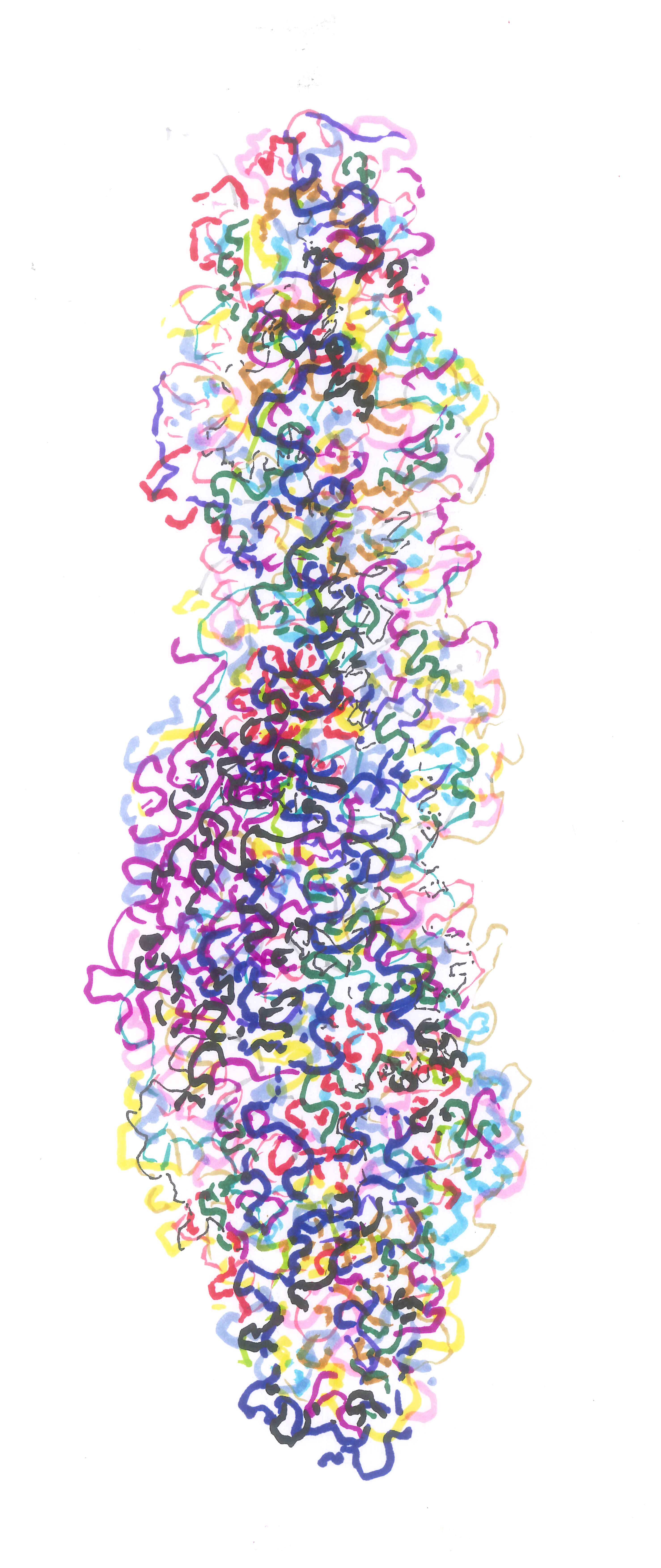

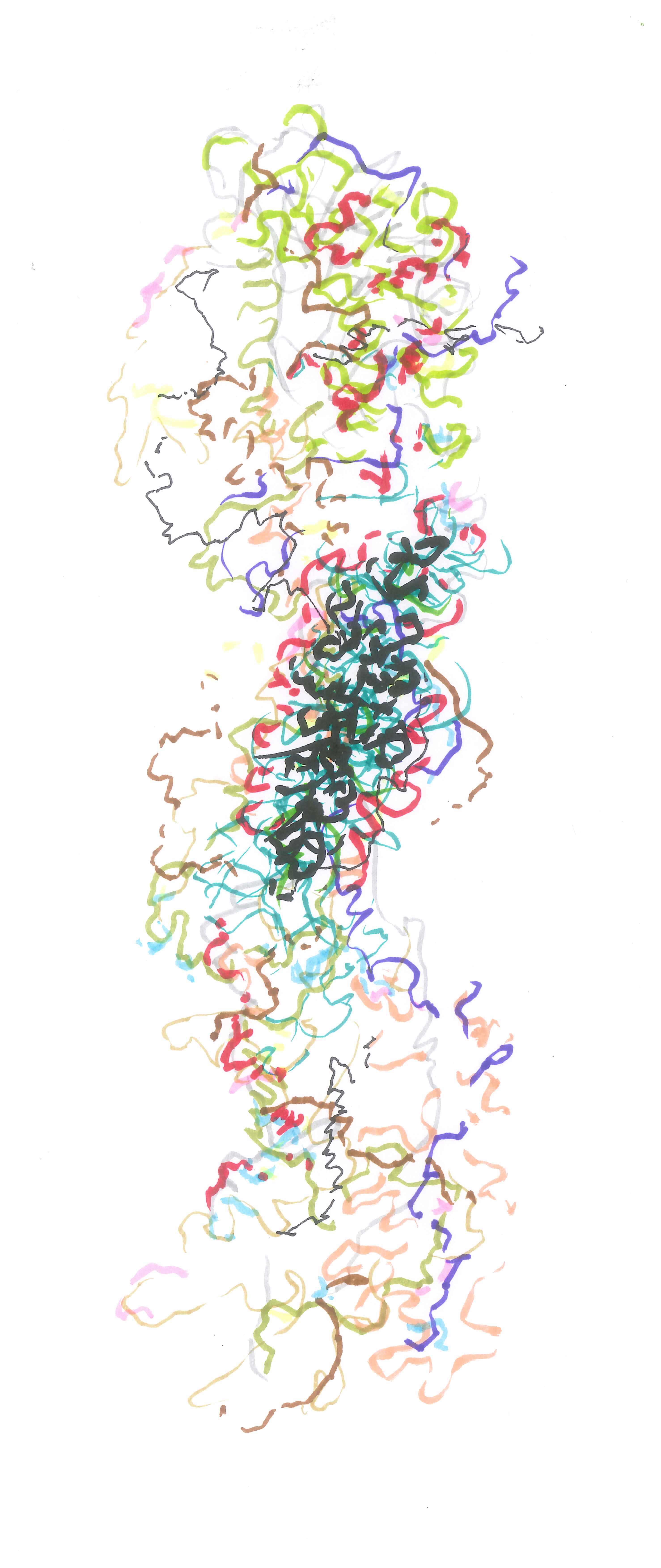

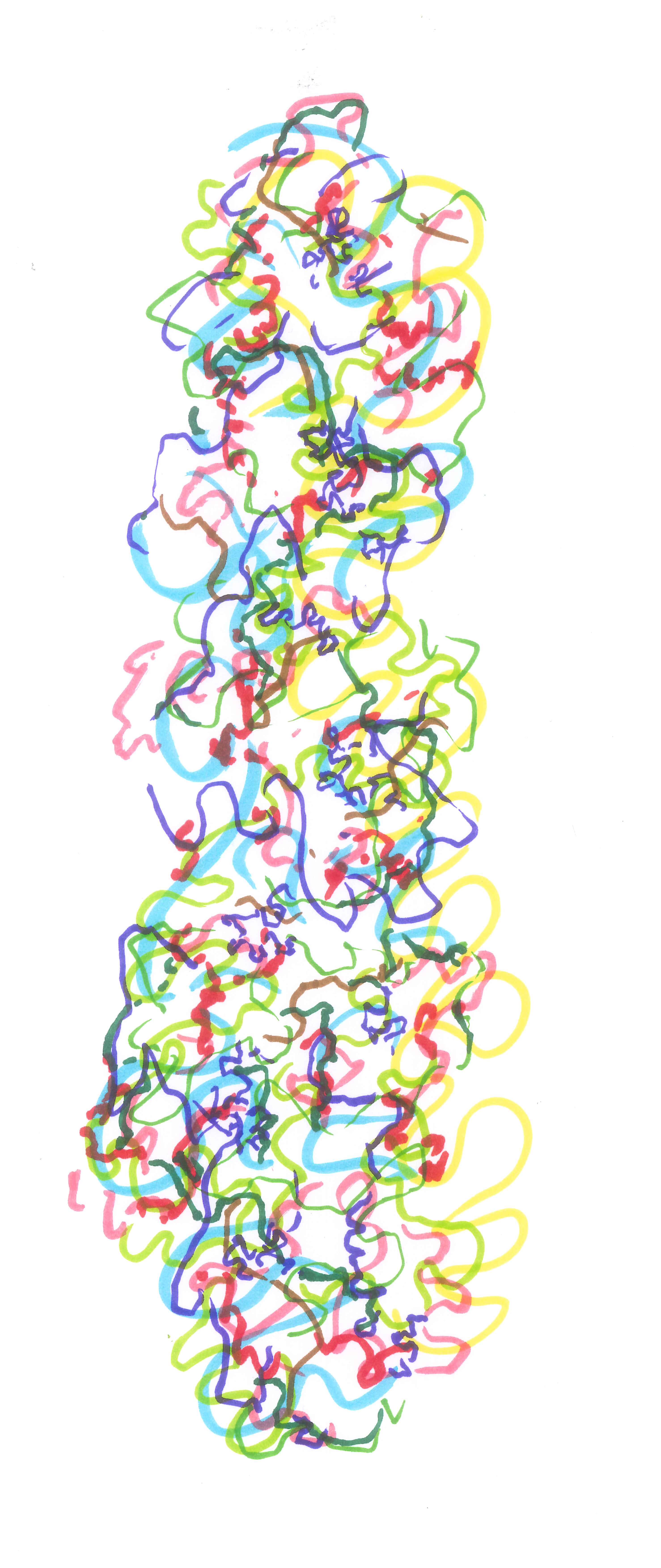

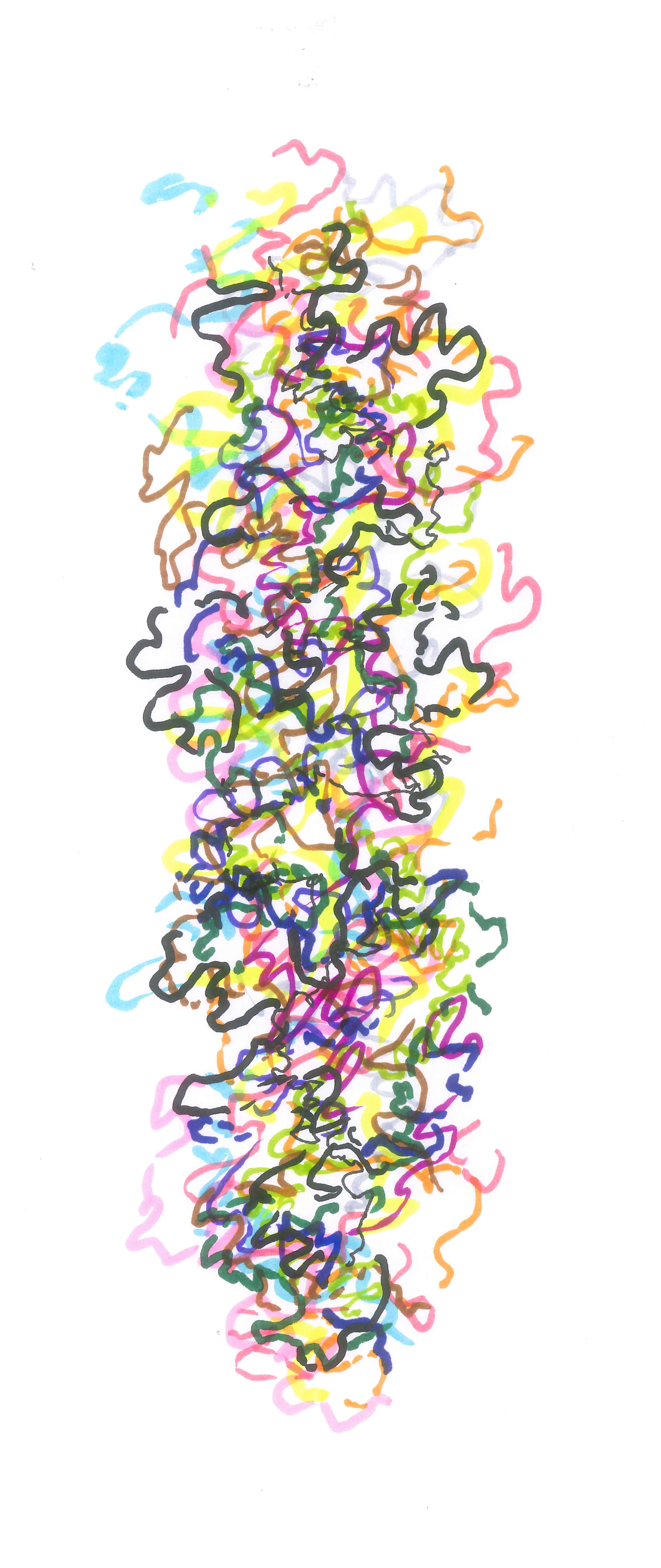

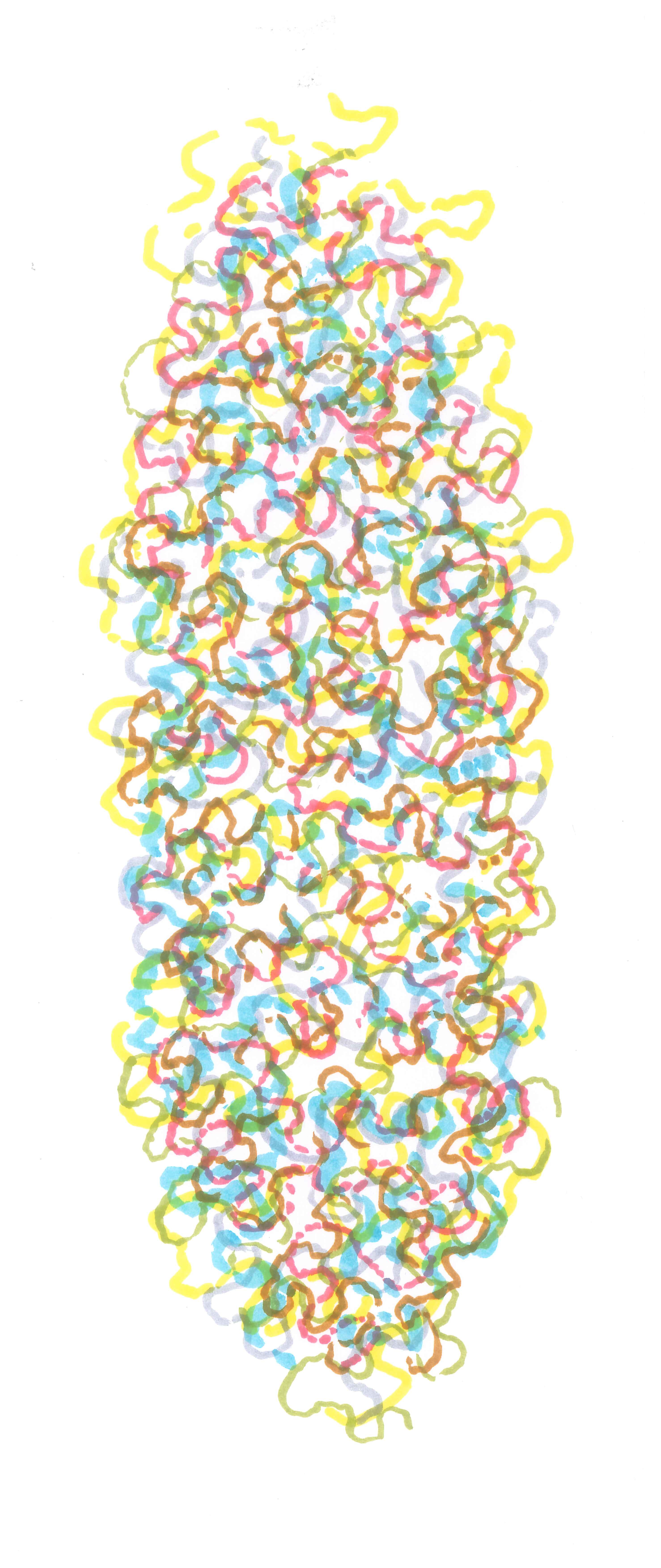

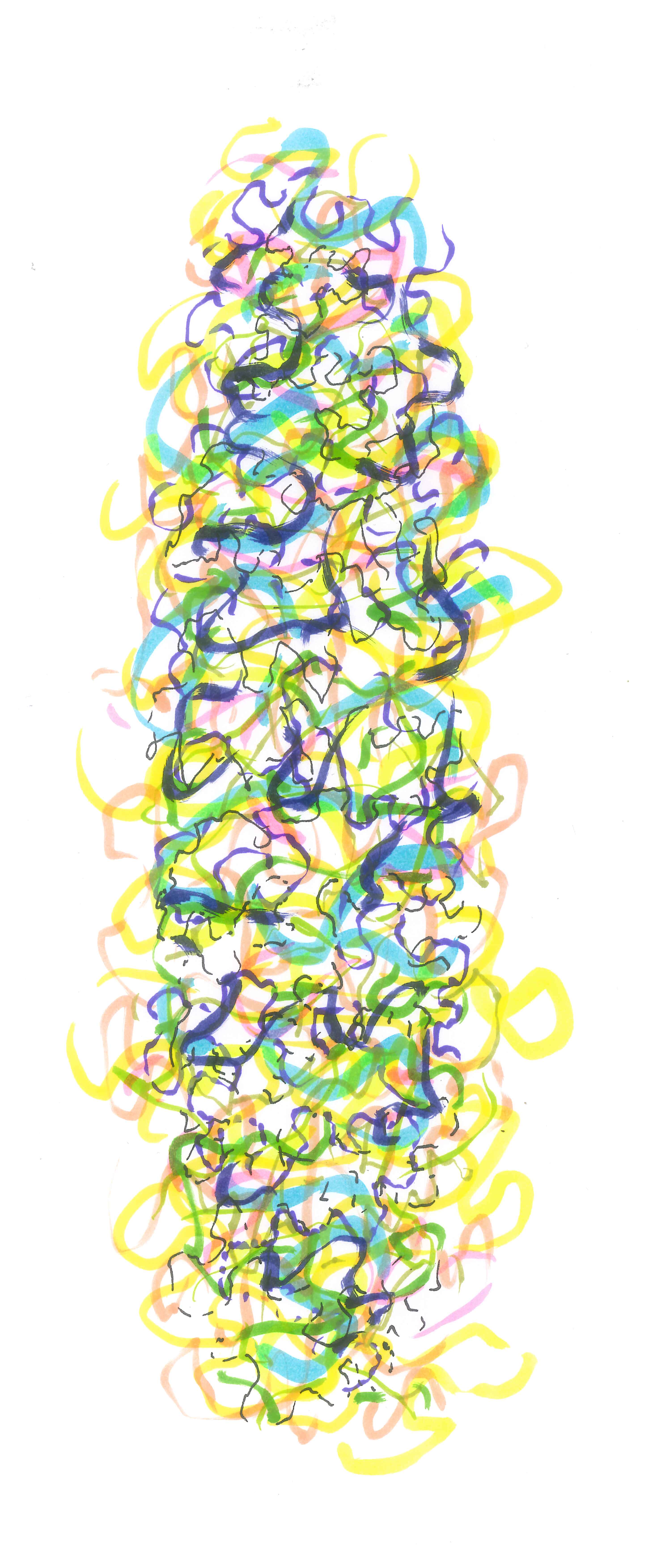

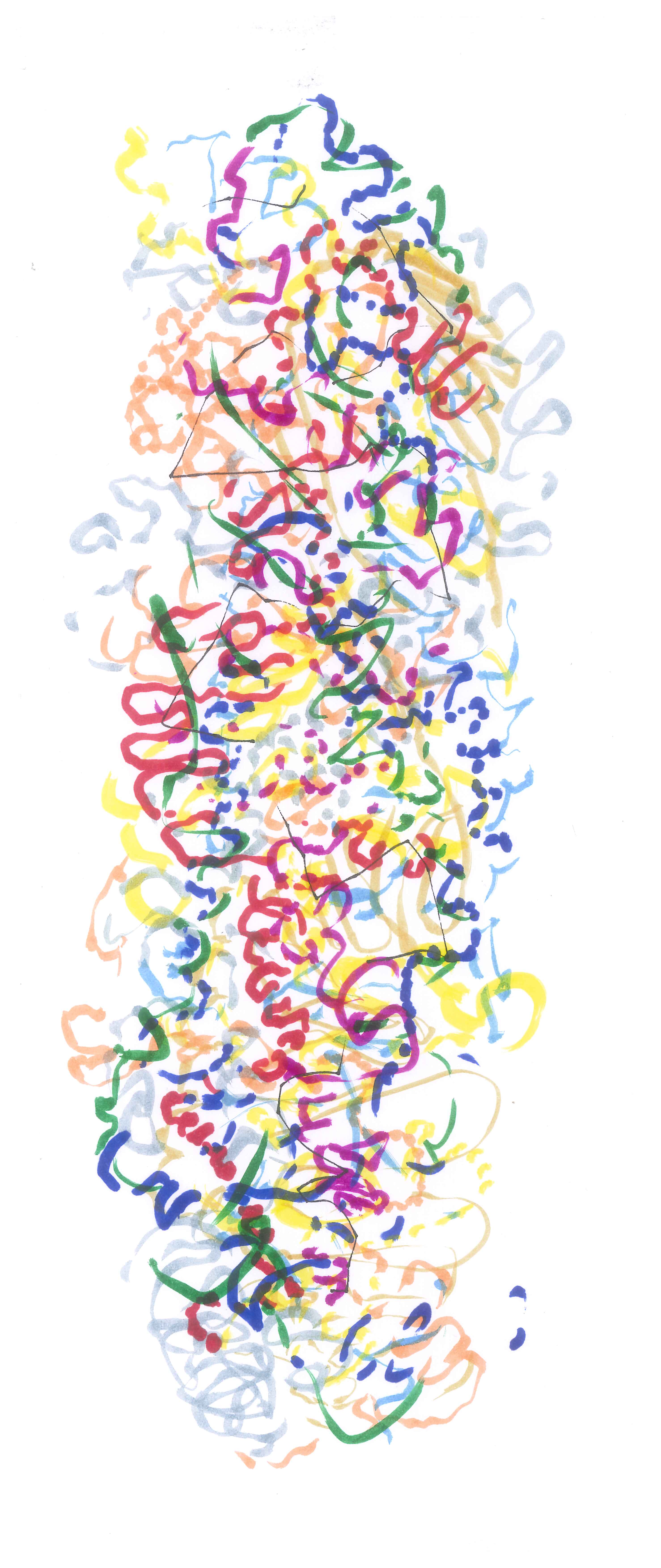

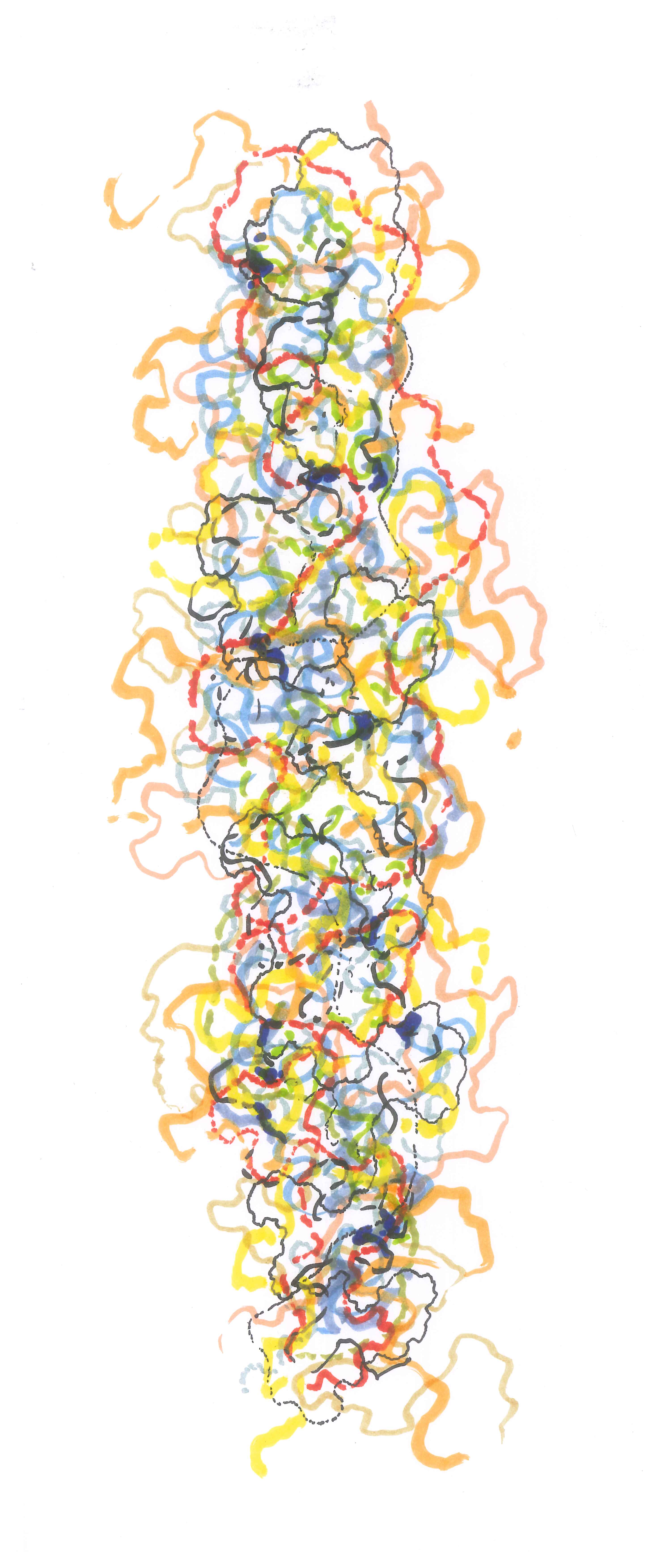

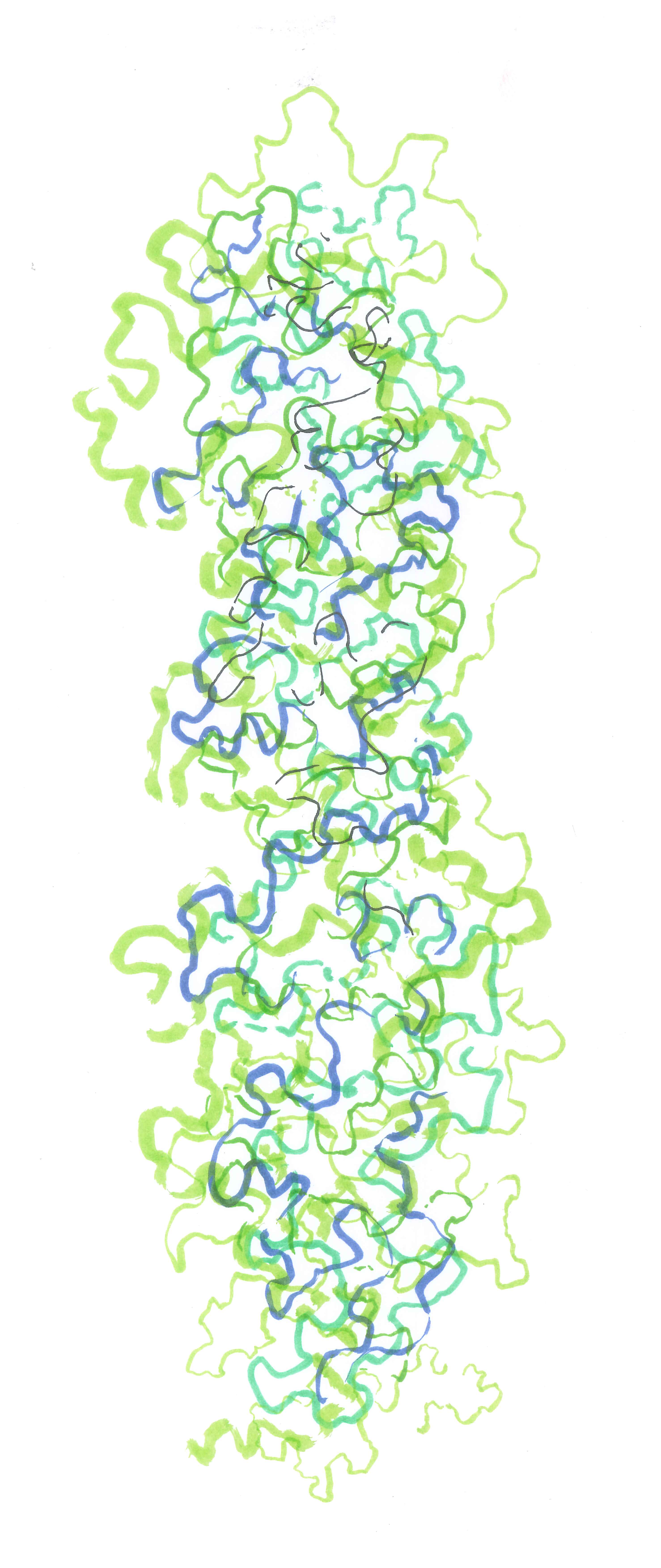

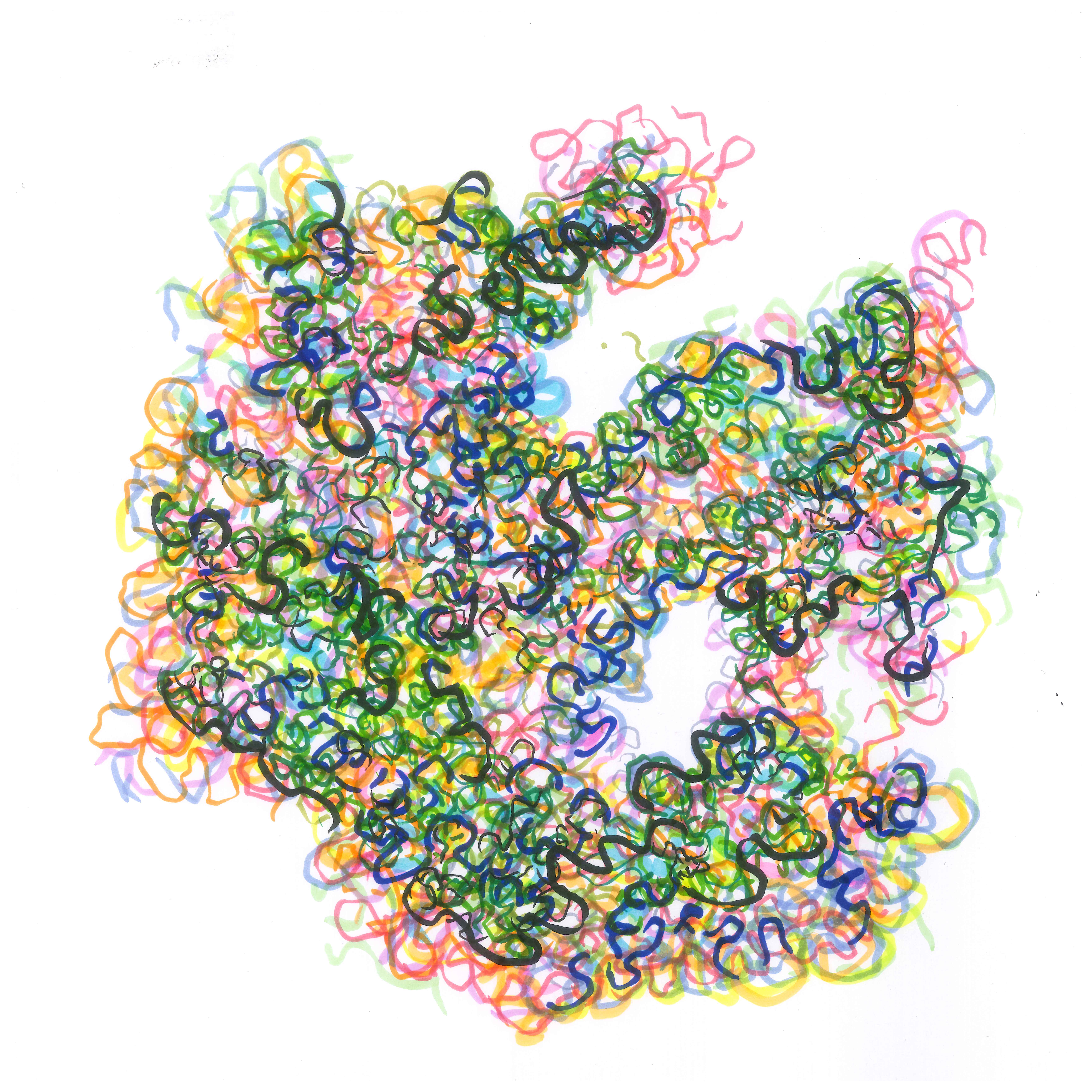

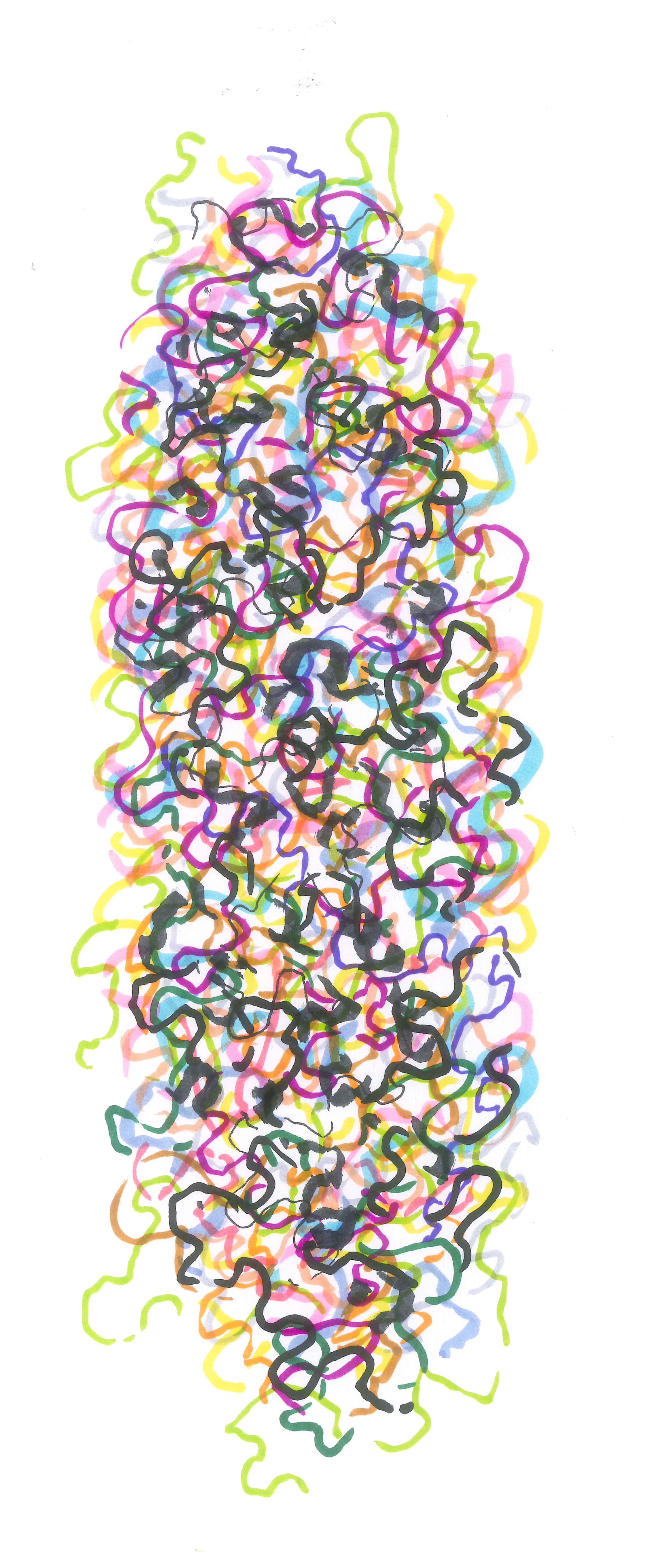

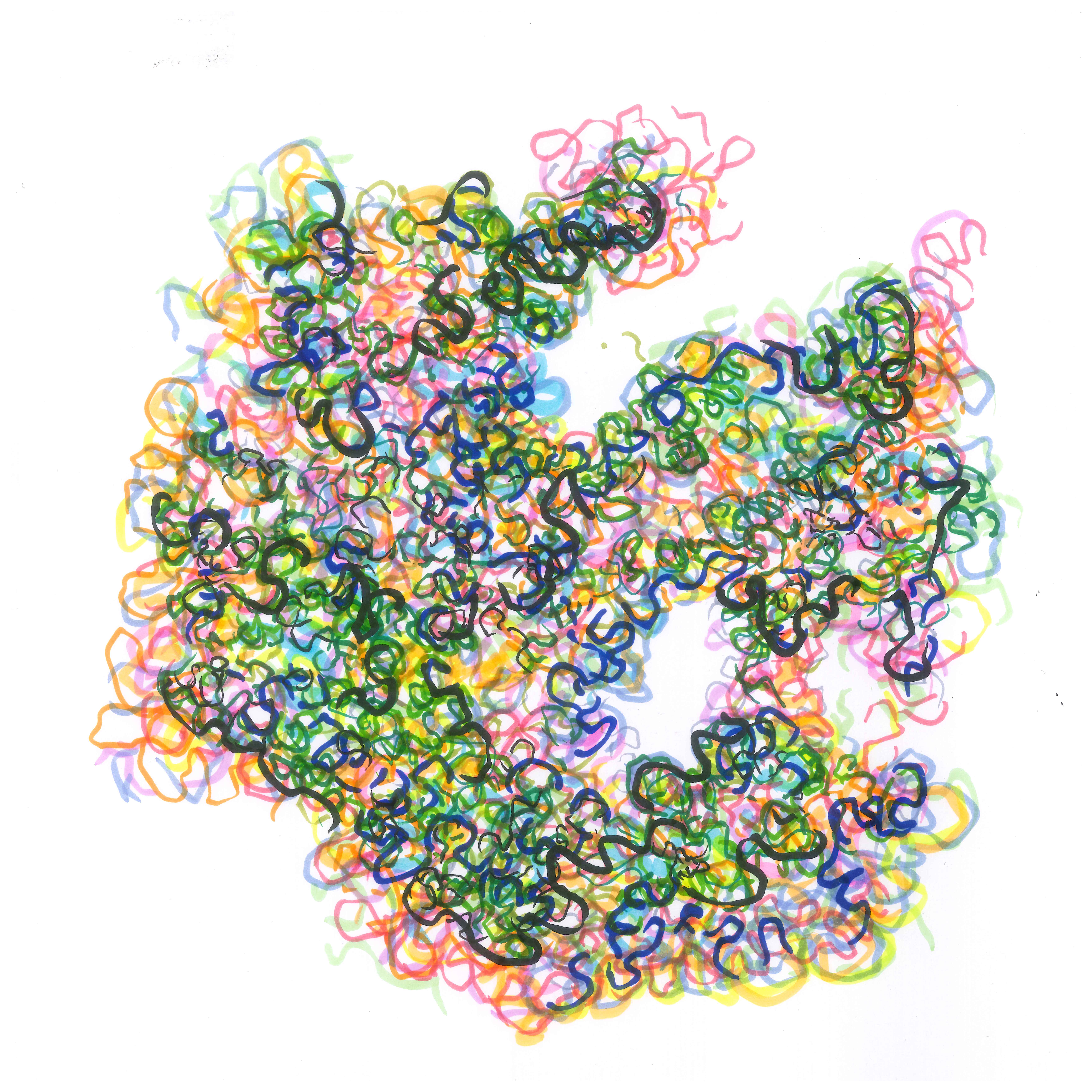

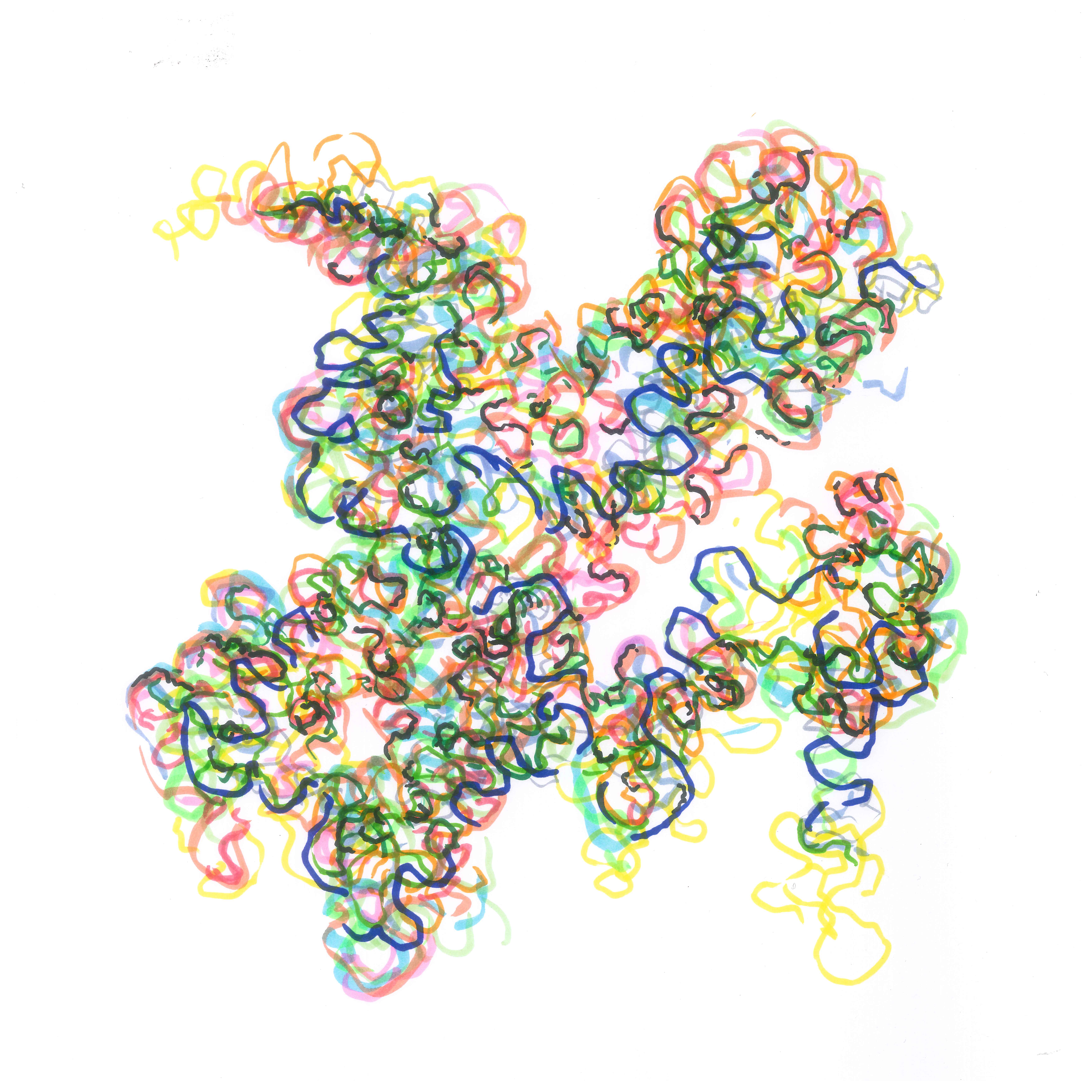

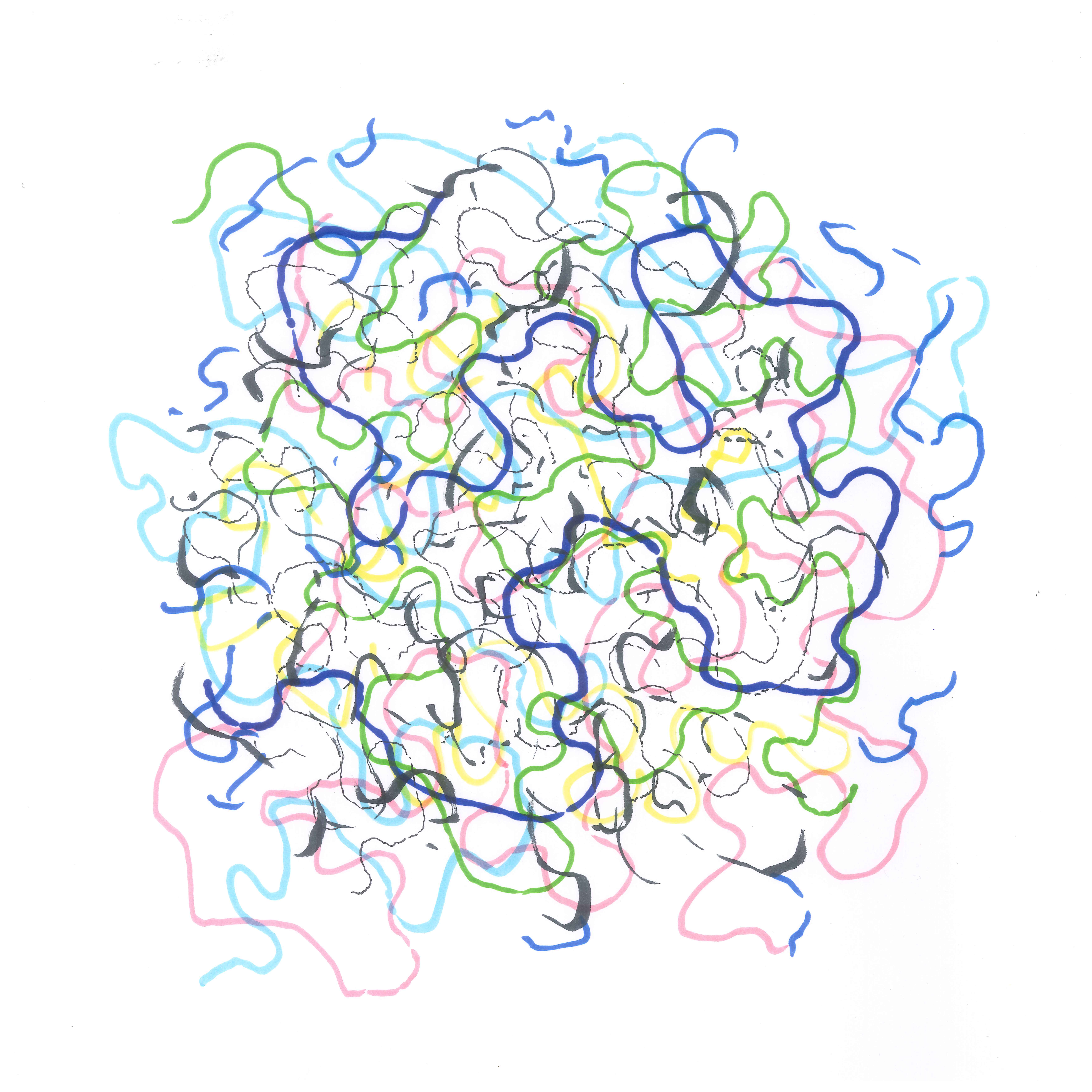

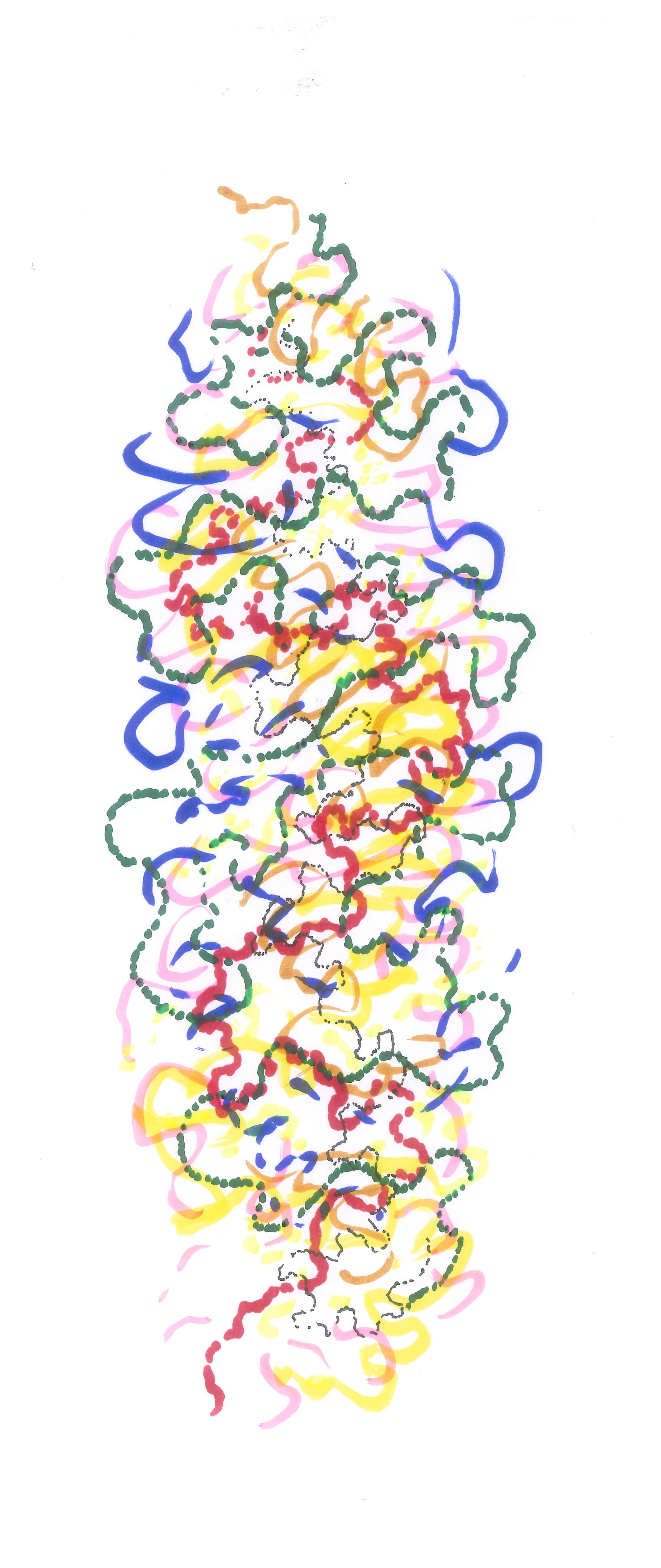

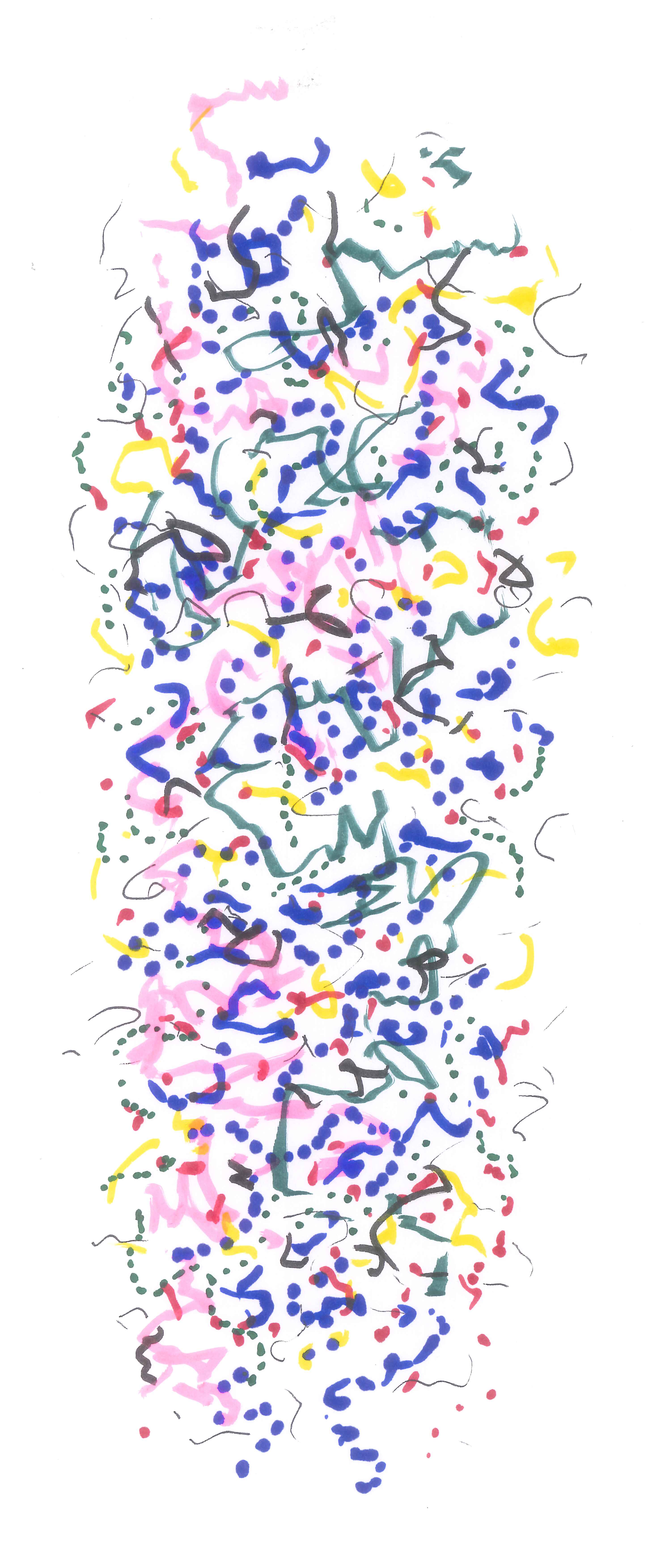

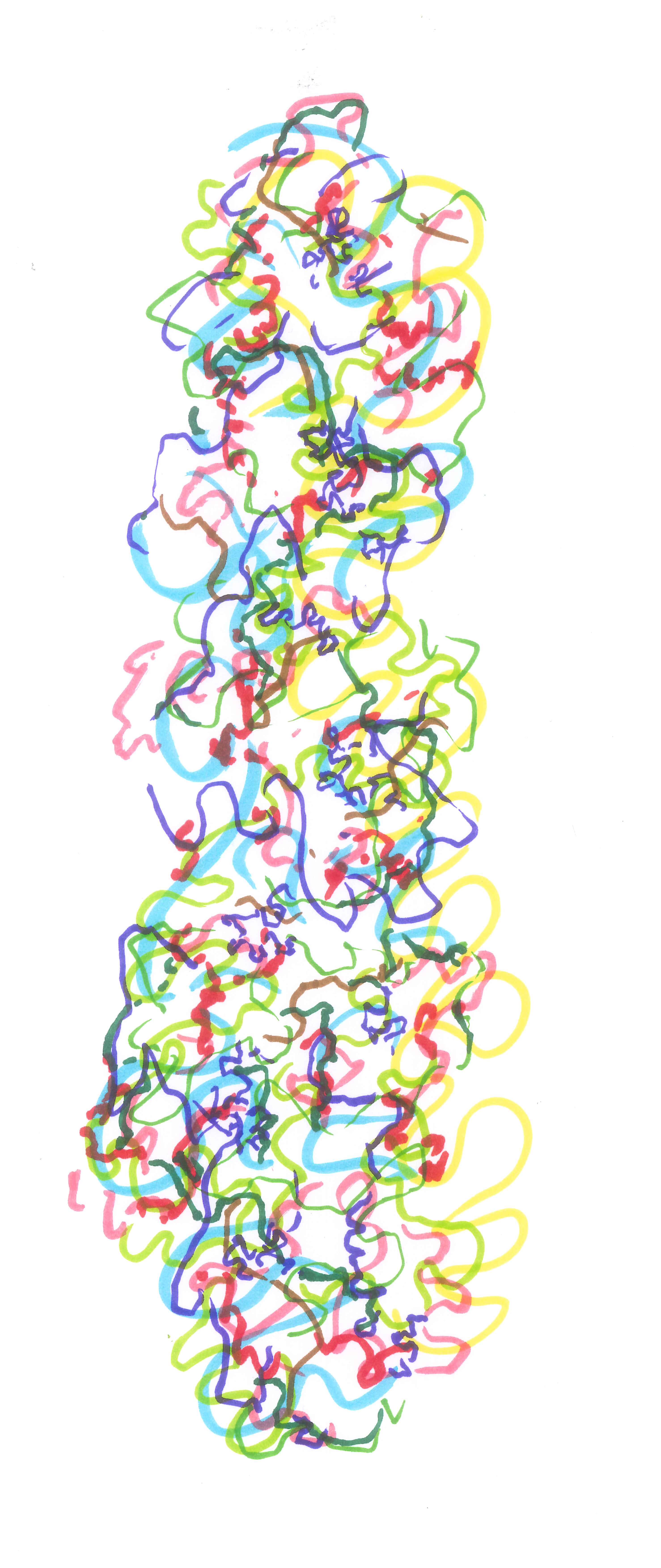

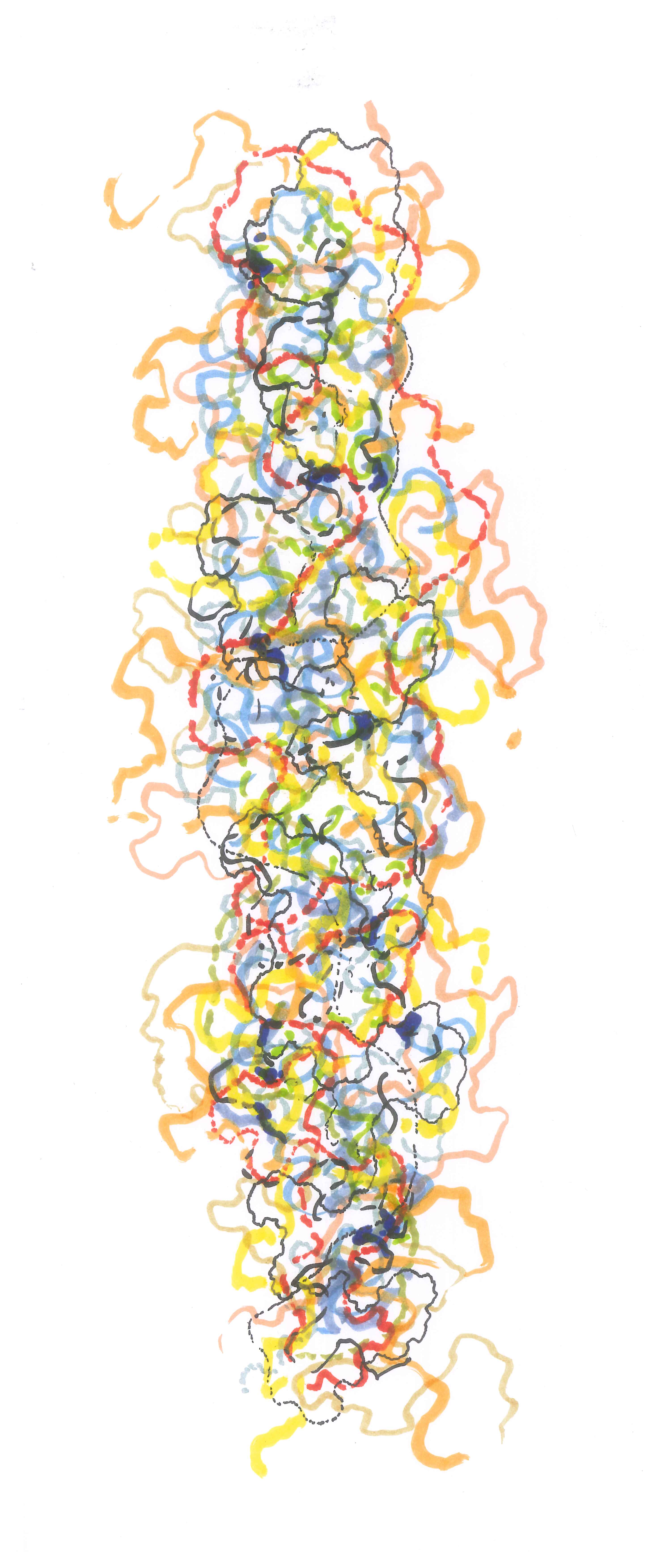

Non-representational painting, i.e. that which explores its own essence, unfolds between the two

extremes of geometric formalism and Art Informel. The former seeks the essence in the sophisticated

differentiation of proportions, while the latter persues the immediacy of the unfiltered painterly gesture.

Art Informal aims to overcome the manufactured nature of the artwork. The hand is not guided by the

controlling eye, but reacts directly to the impulses of an inner tension that discharges itself in nervous

twitches. The eye turns away and the hand is released as if it were an independently thinking entity.

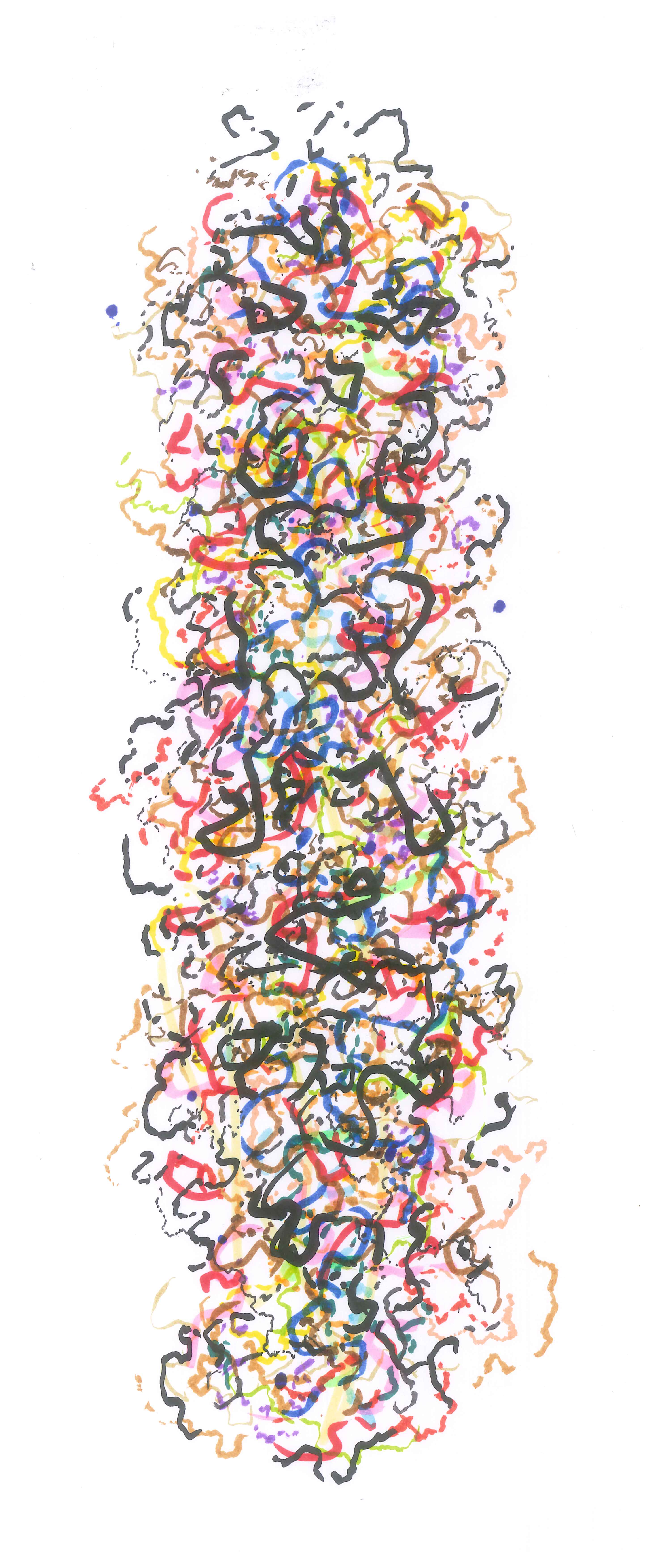

On the other hand, the artist is always and first and foremost a critical observer of their own creative act.

What the picture communicates ultimately is the evaluation of a controlled process. What the free hand

achieves must therefore stand up to the eye's judgement. Otherwise we could content ourselves with

children's drawings and would not have to create immediacy through an artistic process. The eye takes

over the editing: it brings the whole thing to a state. It decides on the choice of colours and painting tools

and it decides at which point the process is stopped and whether the result is released or destroyed.

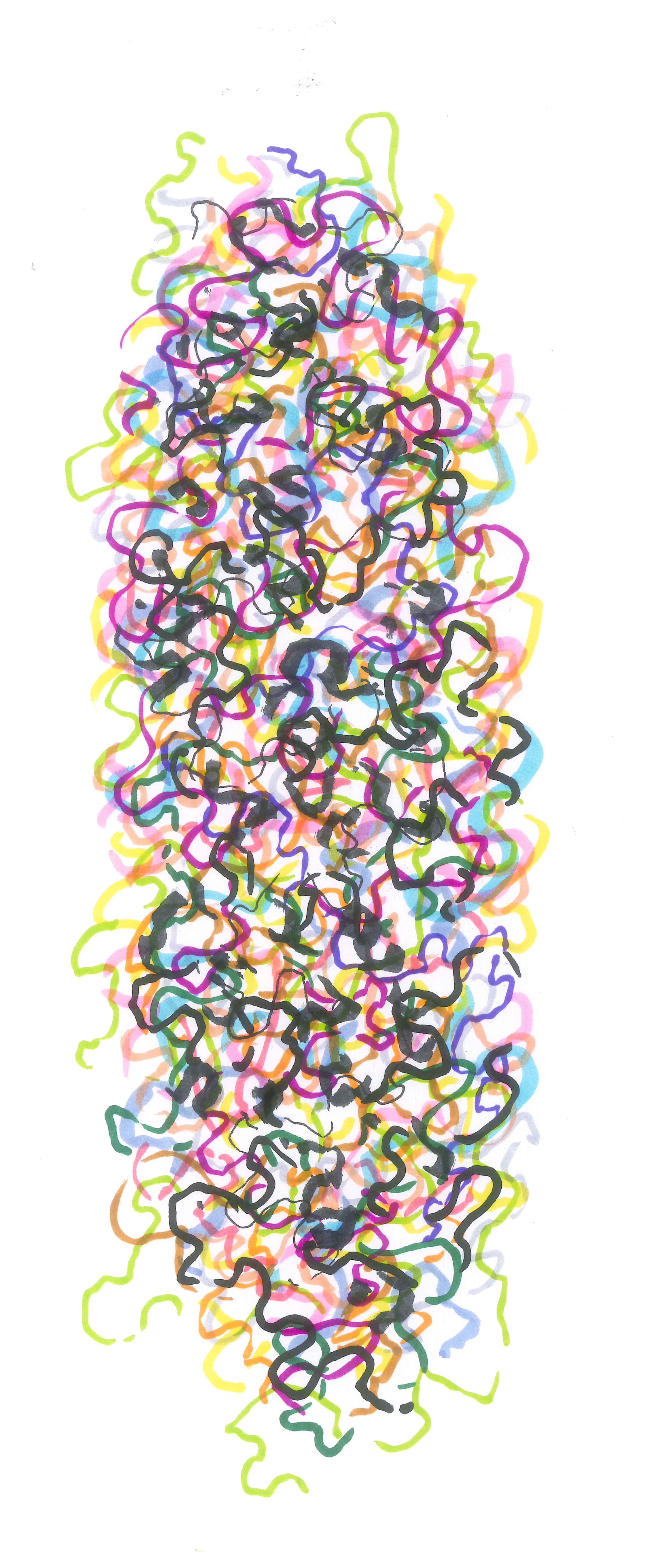

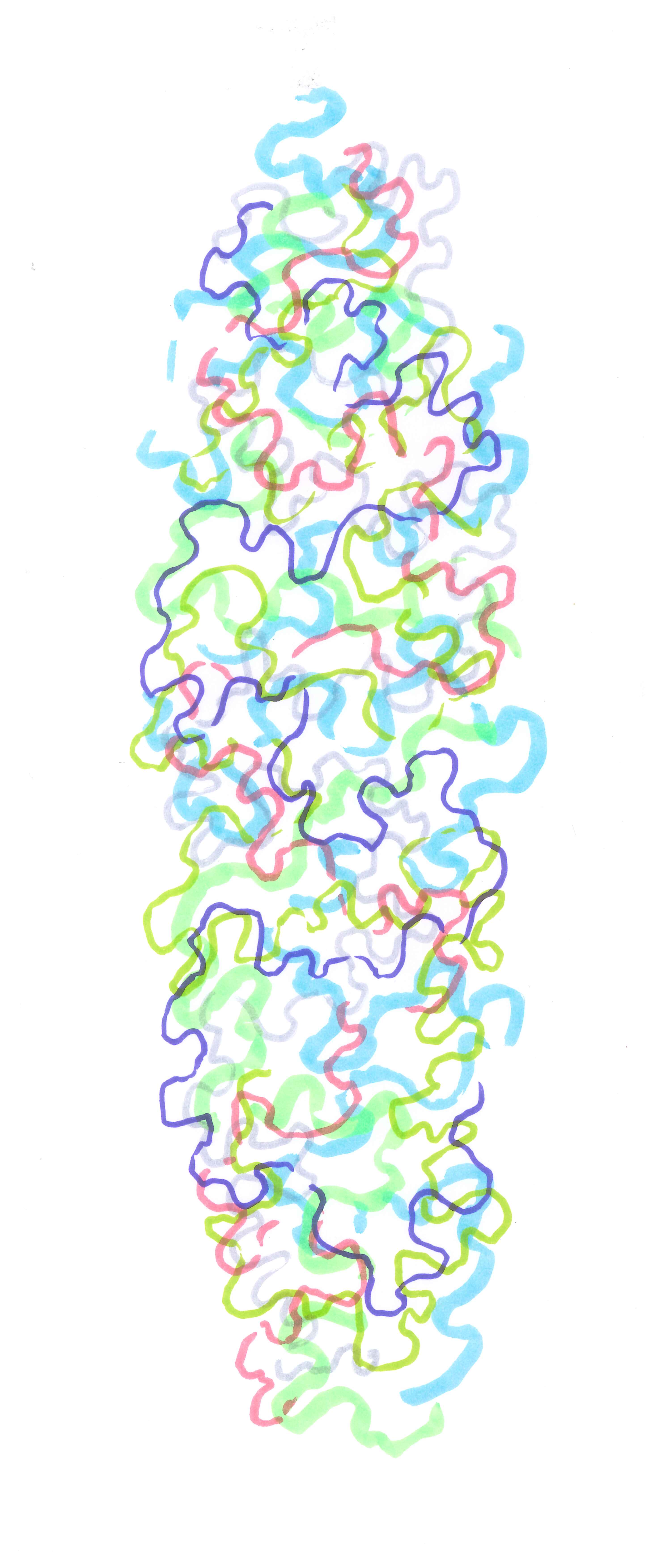

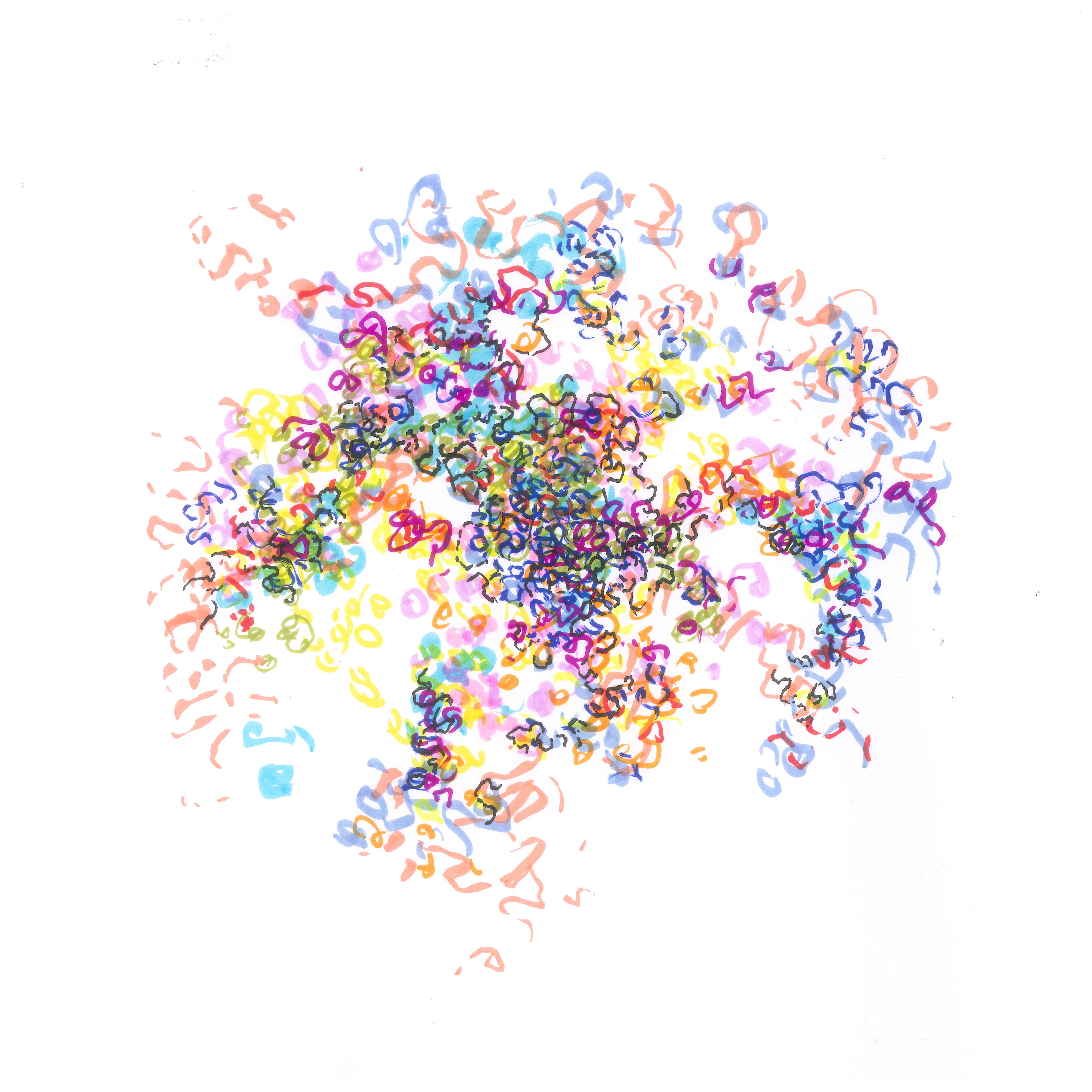

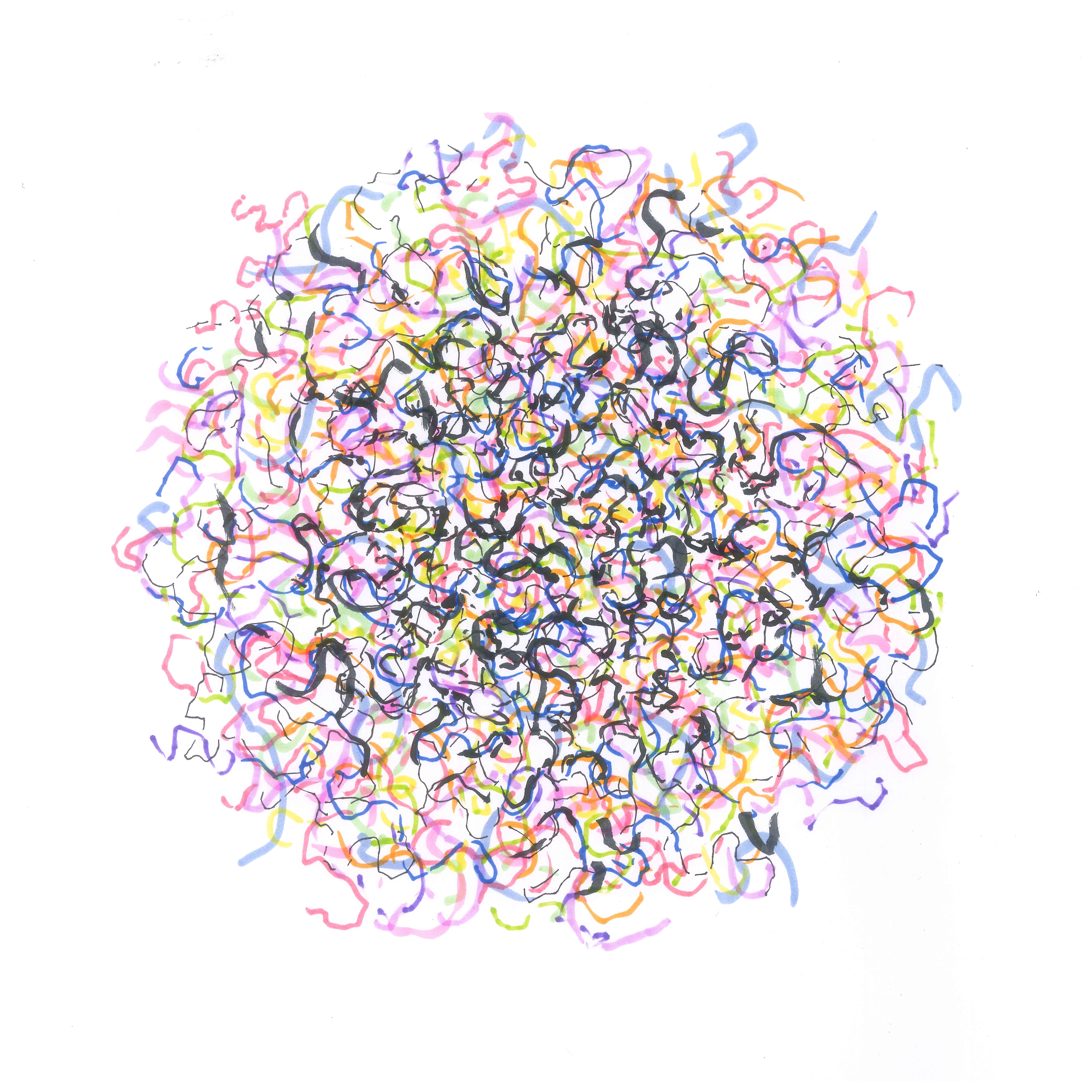

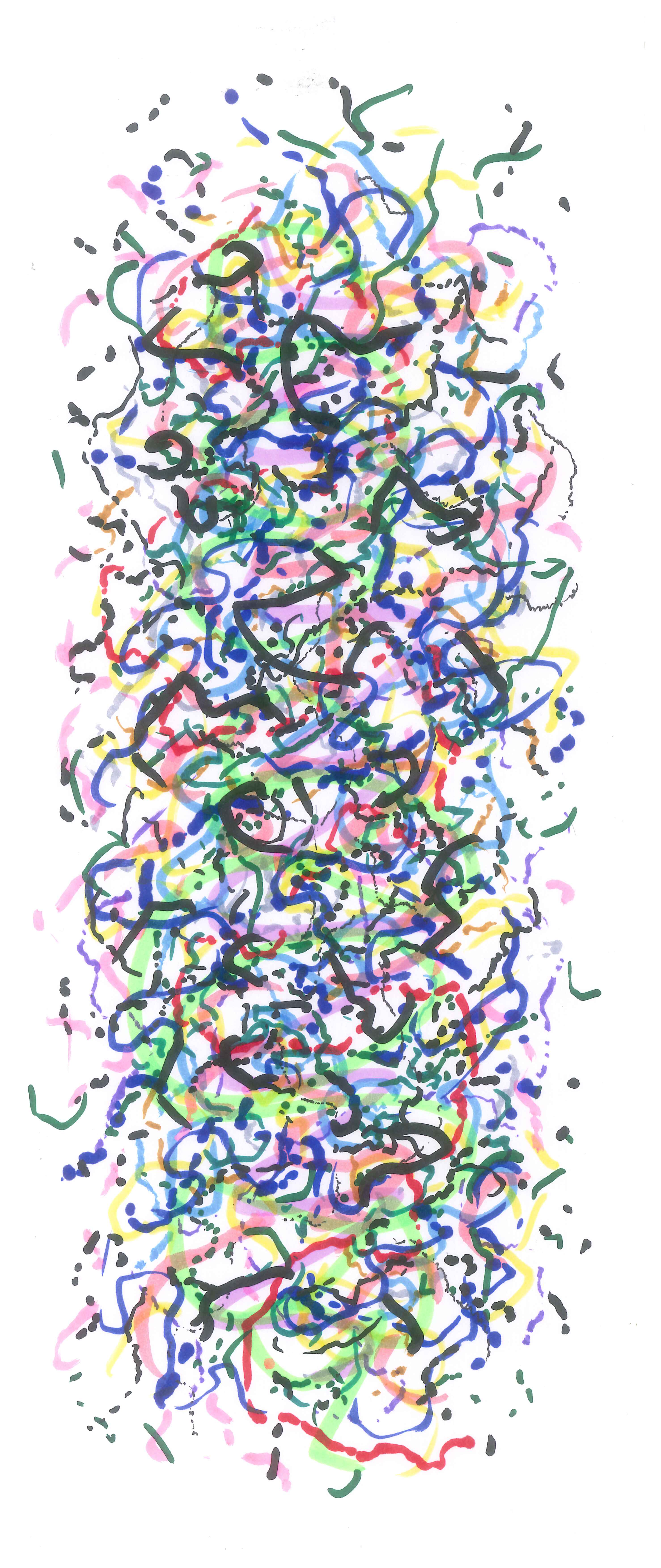

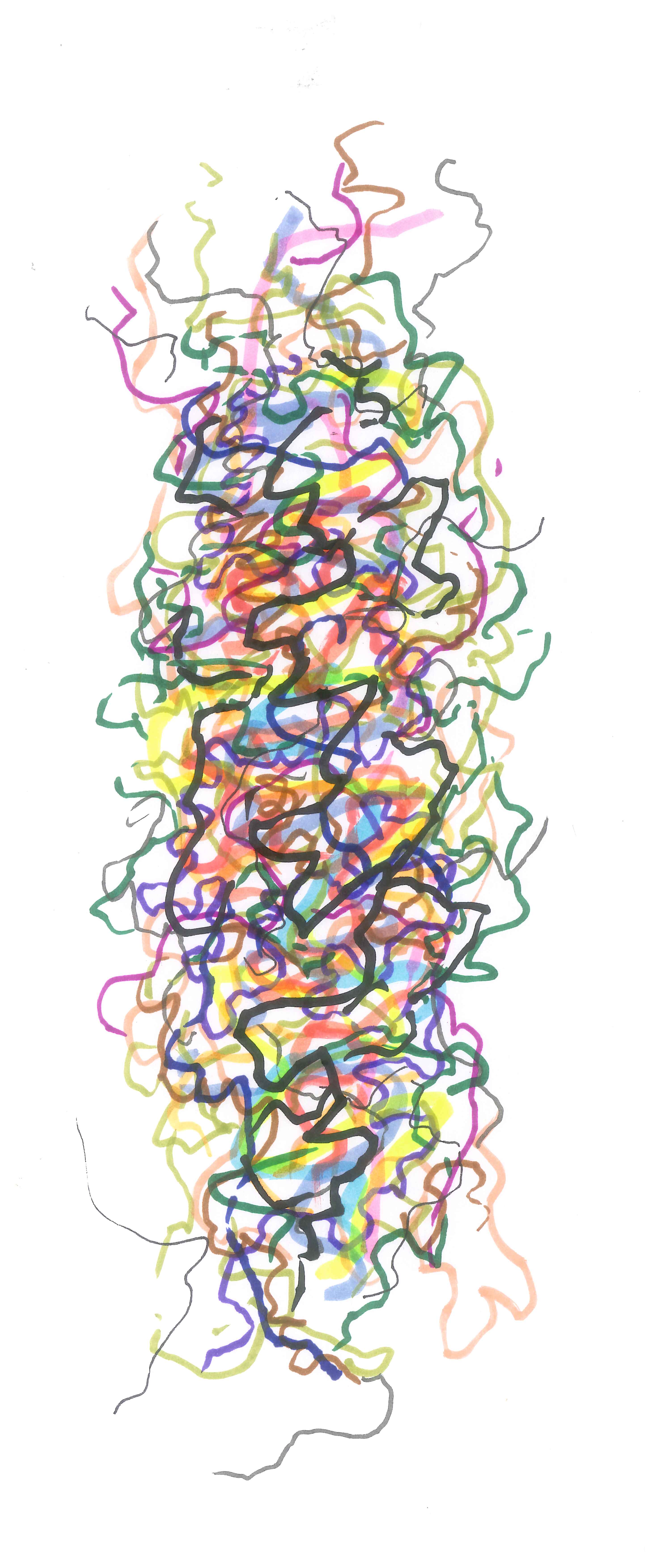

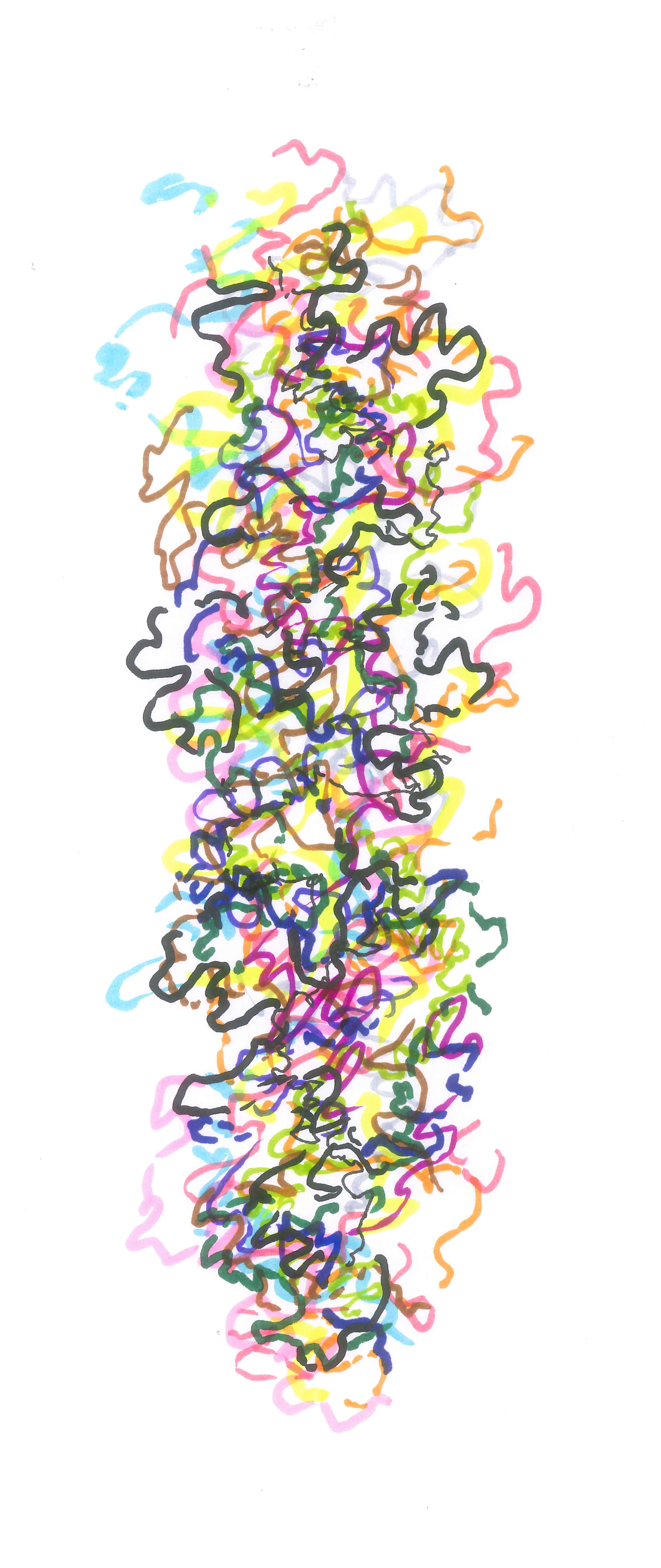

But what criteria does it use to intervene? Is there an aesthetic legal basis? In geometric abstraction there

is one. The dimensions are weighed up. There is always a justification for every measure and every colour

tone. And this law of form is what the non-representational image represents. In the informal, on the other

hand, this step is skipped. The eye must decide according to its own instict. And this instinct must be

trained. It is similar to hanging a picture. Most people have a sense of whether it is hanging in the right

place or whether it should be moved half an inch up or a little to the left. And in everyday life we have an

unconscious sense of where we place things and how we move around in a space. It's a question of

sensitivity. We sense when something is in the wrong place. And it is precisely this sense that the artist

uses to design an object. Only here does it happen consciously. Sometimes you decide against the

immediate impulse. You intentionally put something in the wrong place and see what happens.

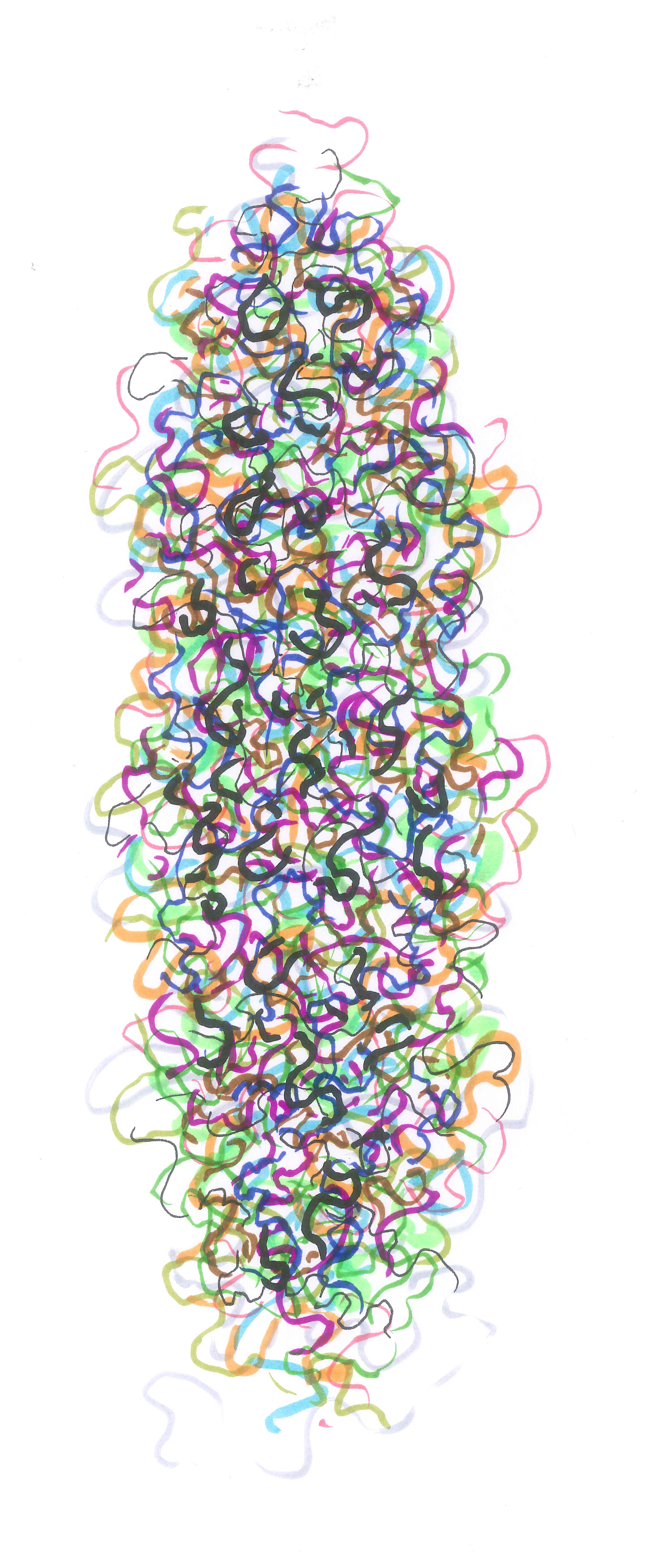

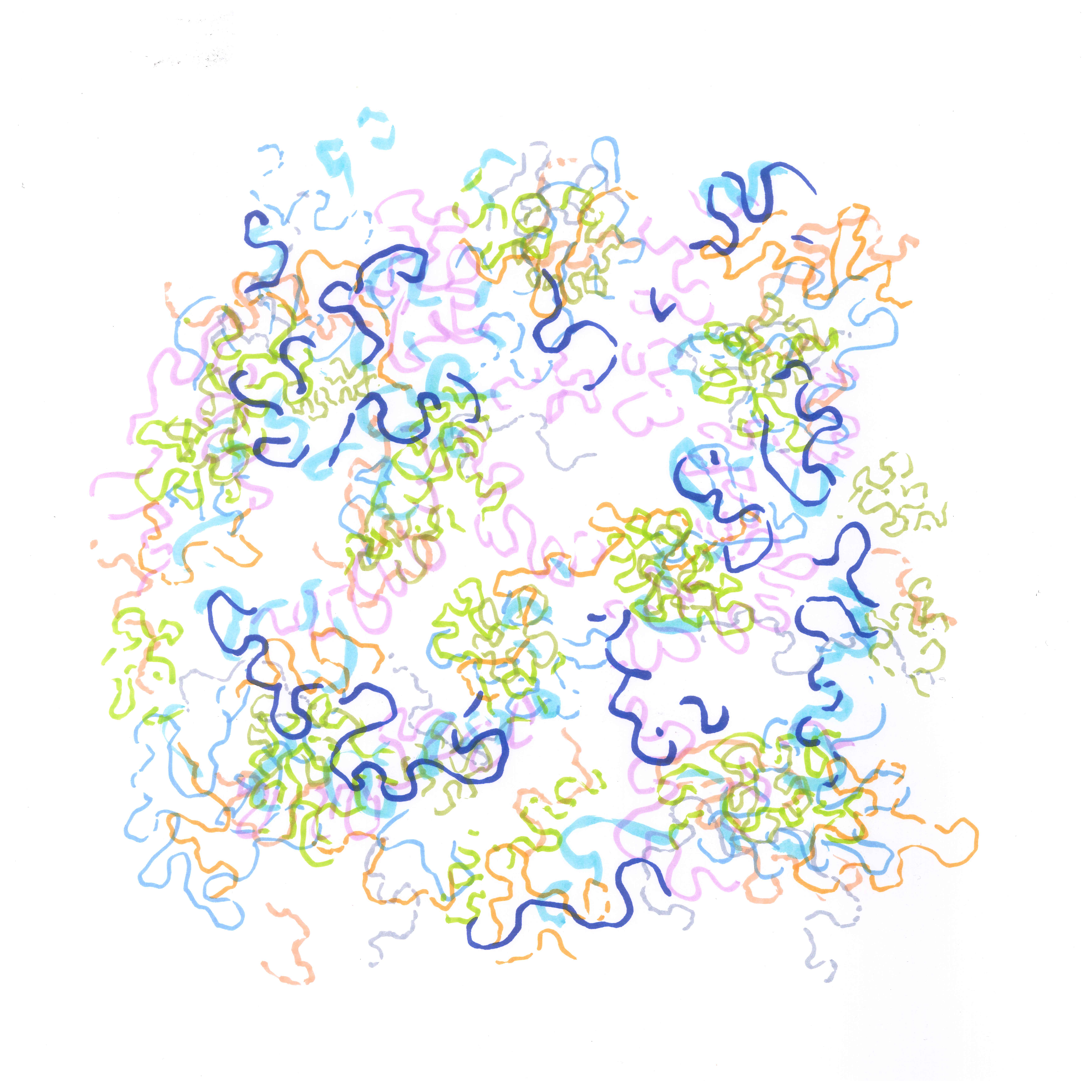

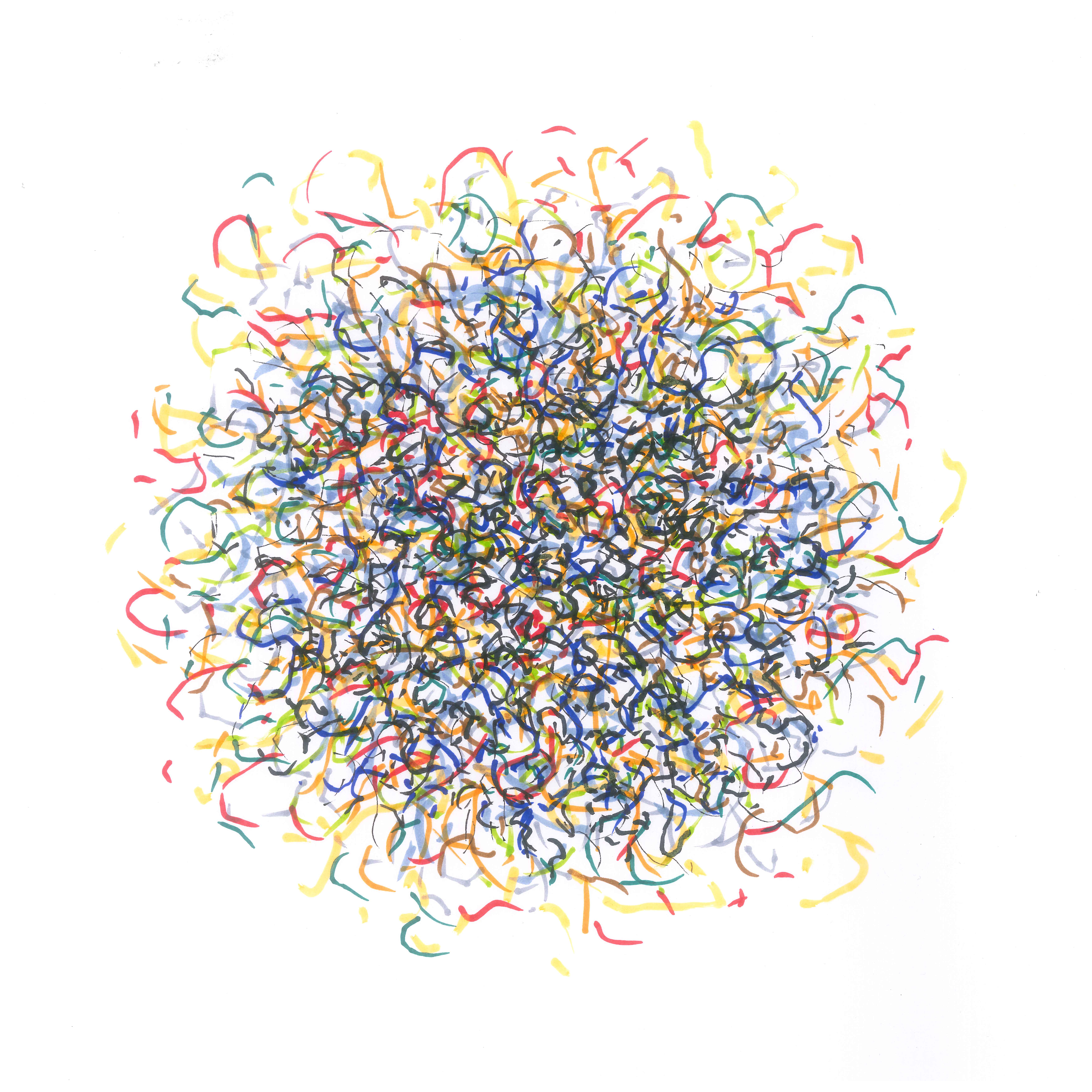

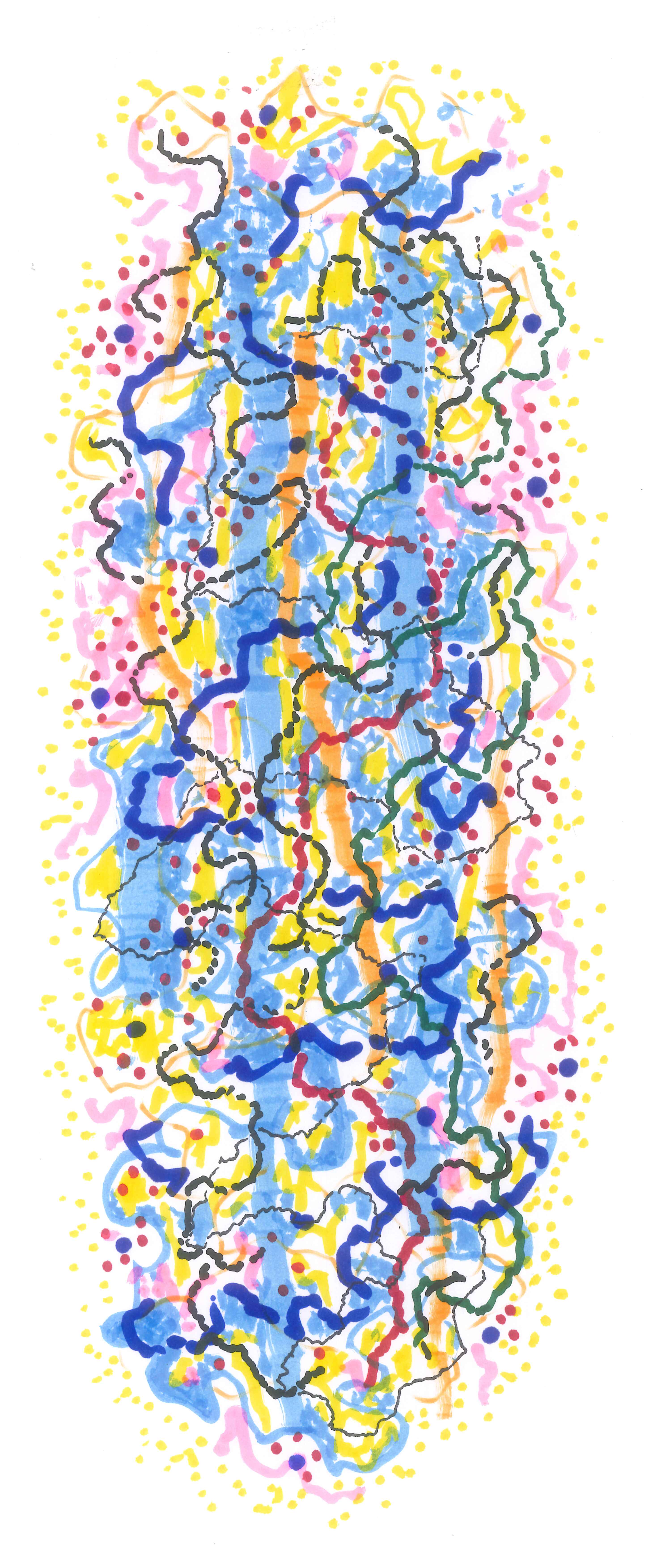

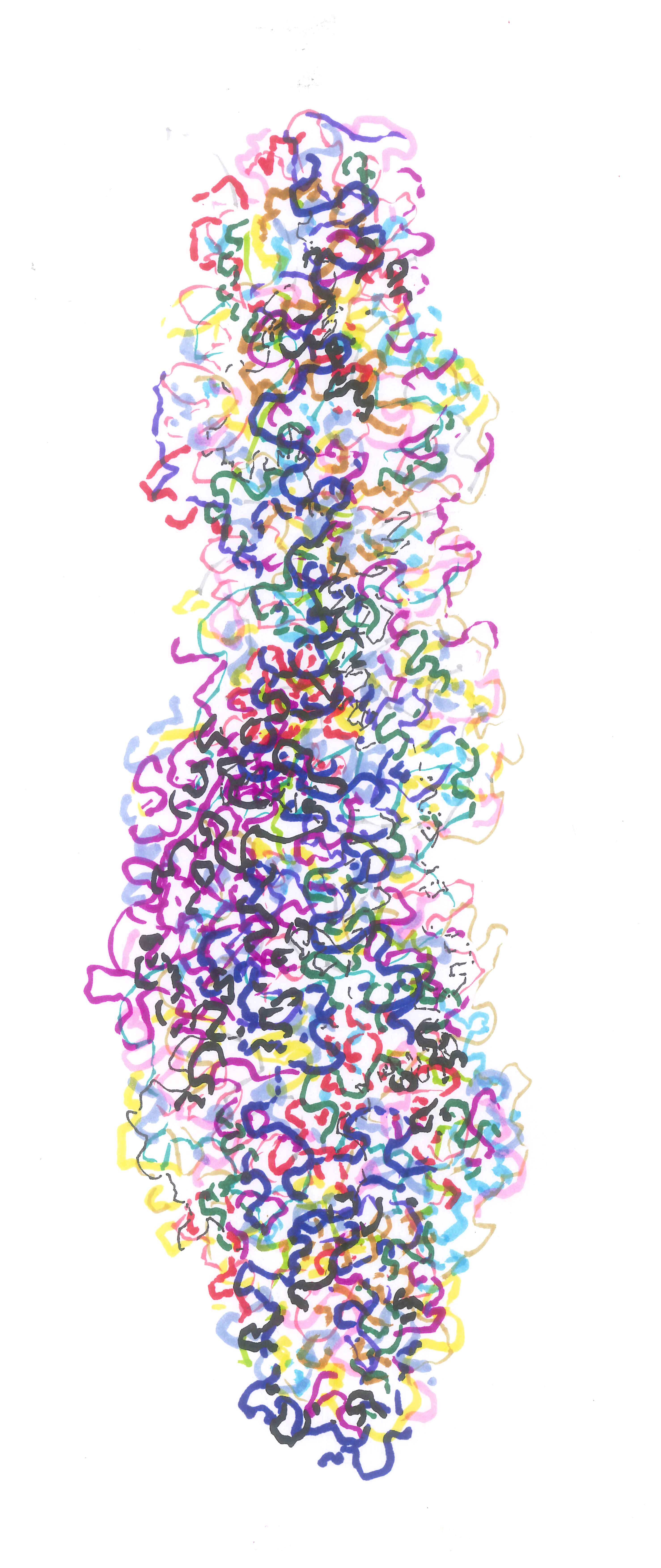

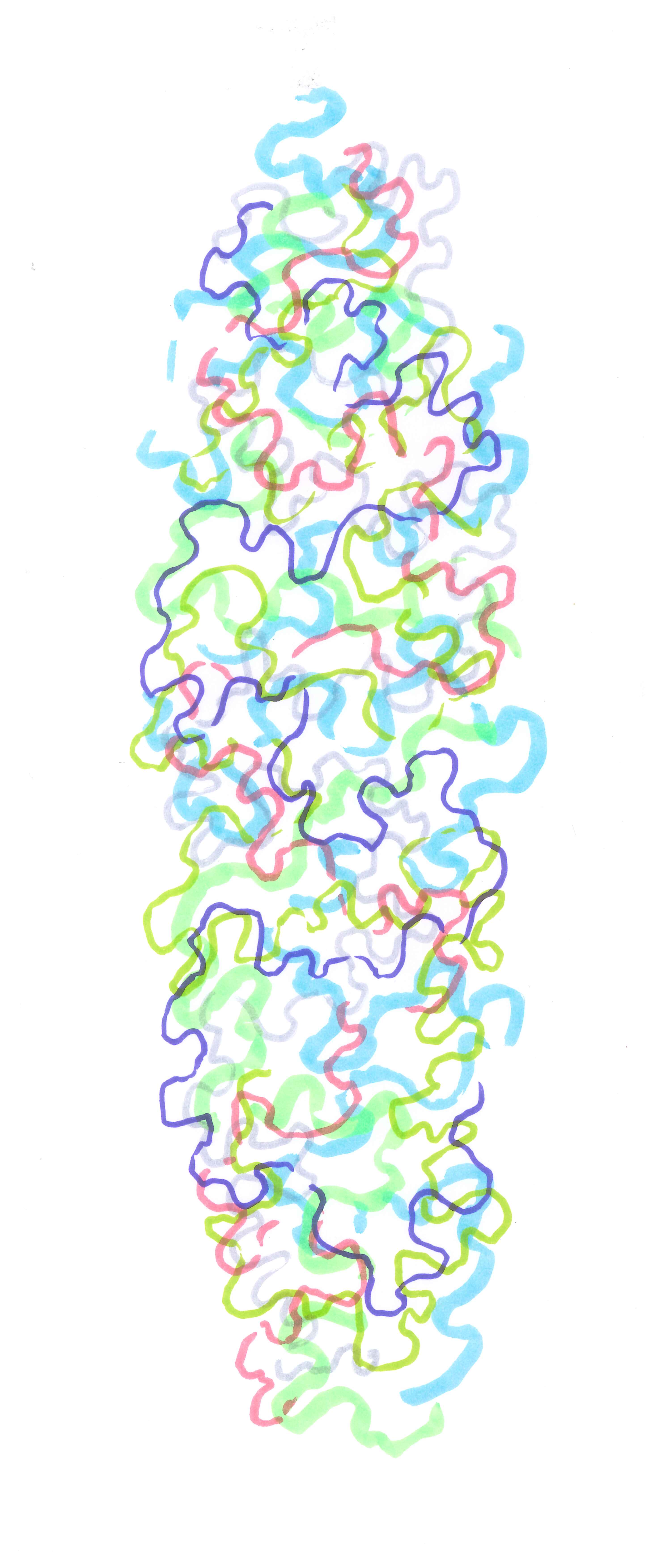

In the end, of course, balance must be established, in whatever form. The tensions must be concentrated.

There is a balance in imbalance, and there is a restlessness in what is at rest. These tensions form the

repertoire of expressive potential. The same applies to geometric abstraction. The relationships between

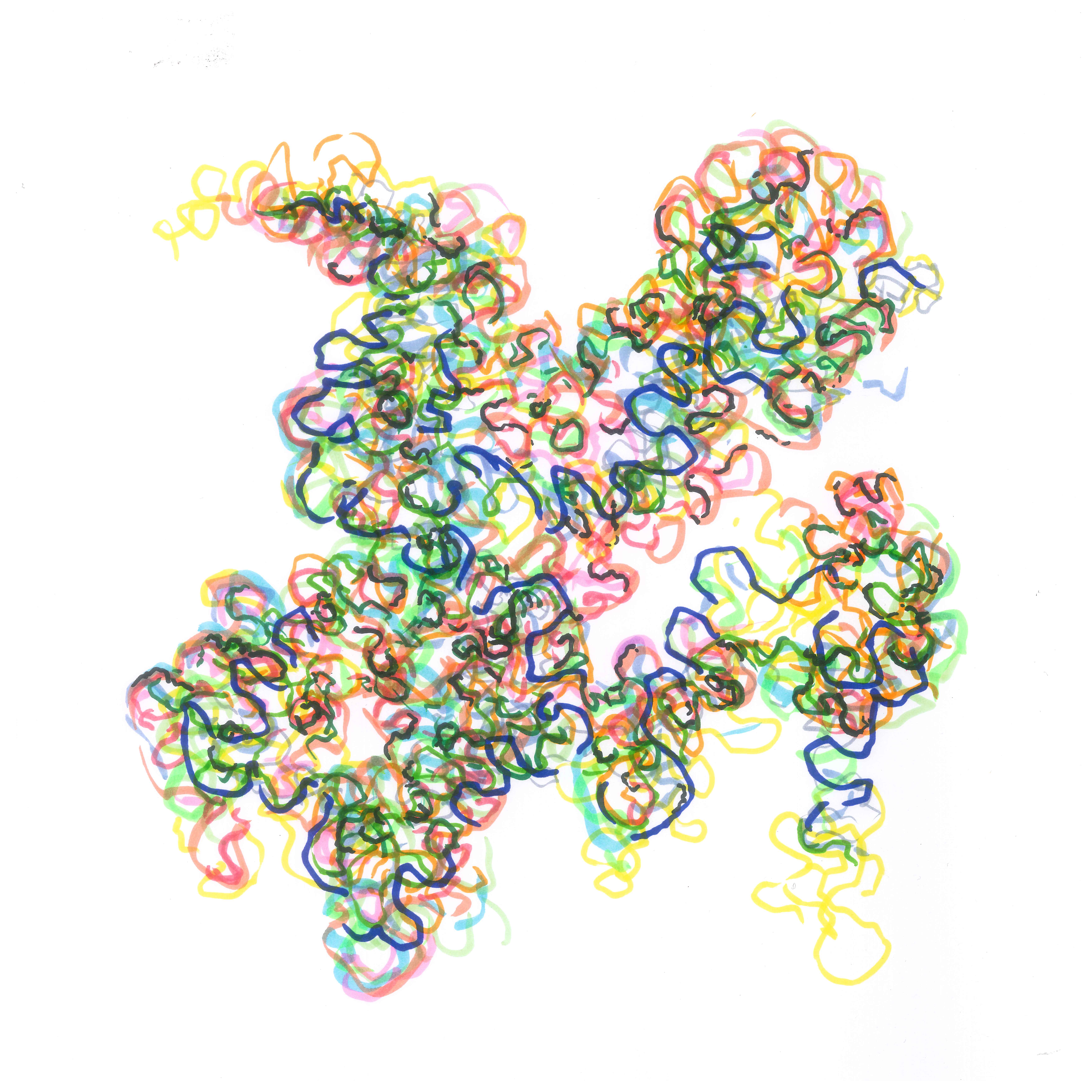

observation and action are different there, but the artistic expression is independent of this. When it

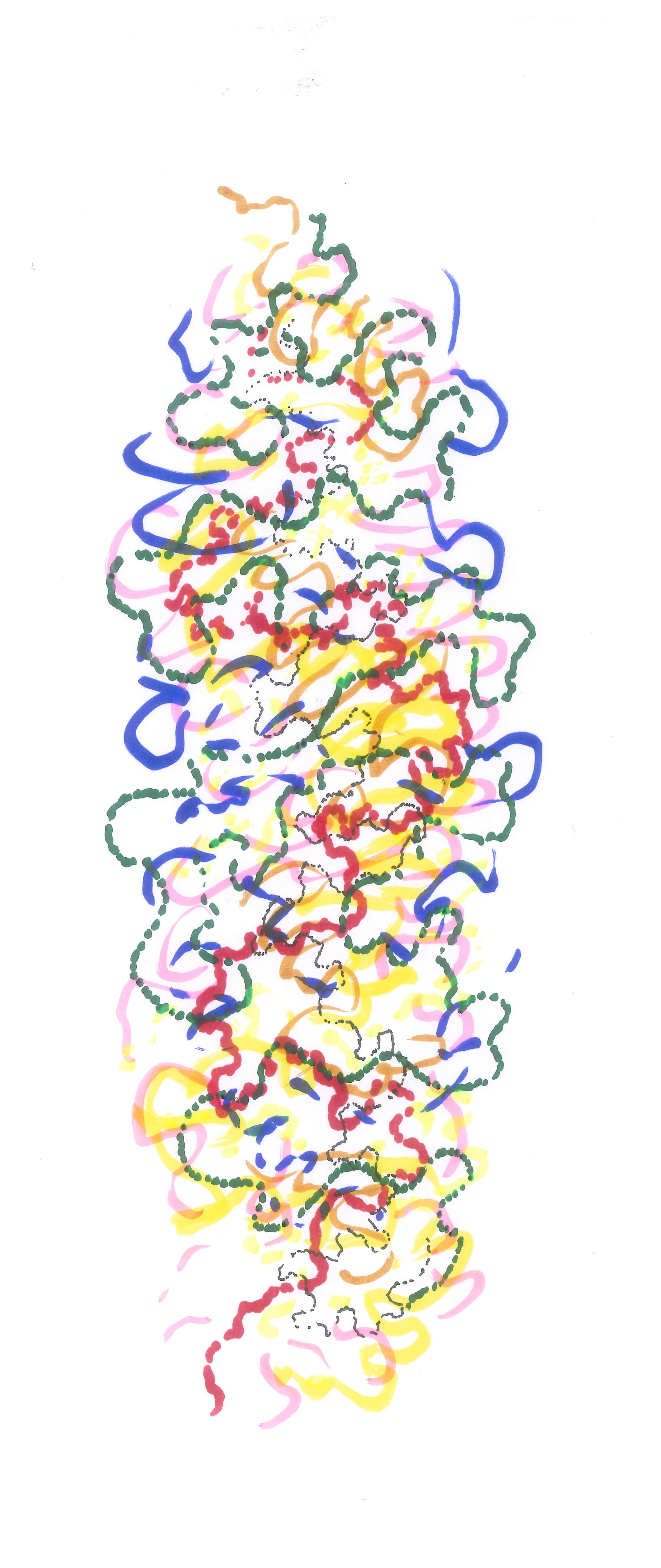

comes to the essence of art, we cannot hang on to the stylistic. What expresses itself, what pushes itself to

the surface, into the form, is always the same. For lack of a better term, I will call it 'creative urge'. Painting

as painting or art as art is always an artist's attempt to bring the inner urge to a perceptible form,

preferably without omitting or adding anything. That is what is called 'inner necessity'.

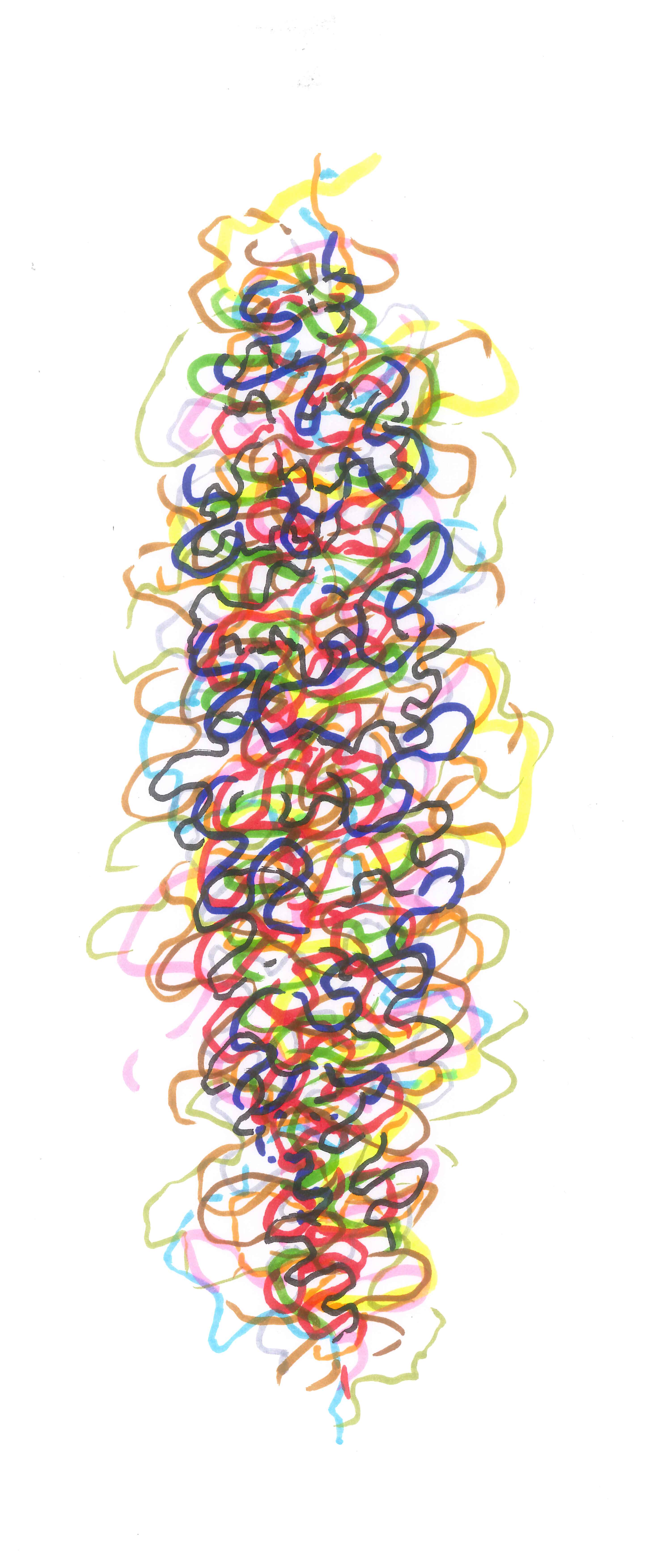

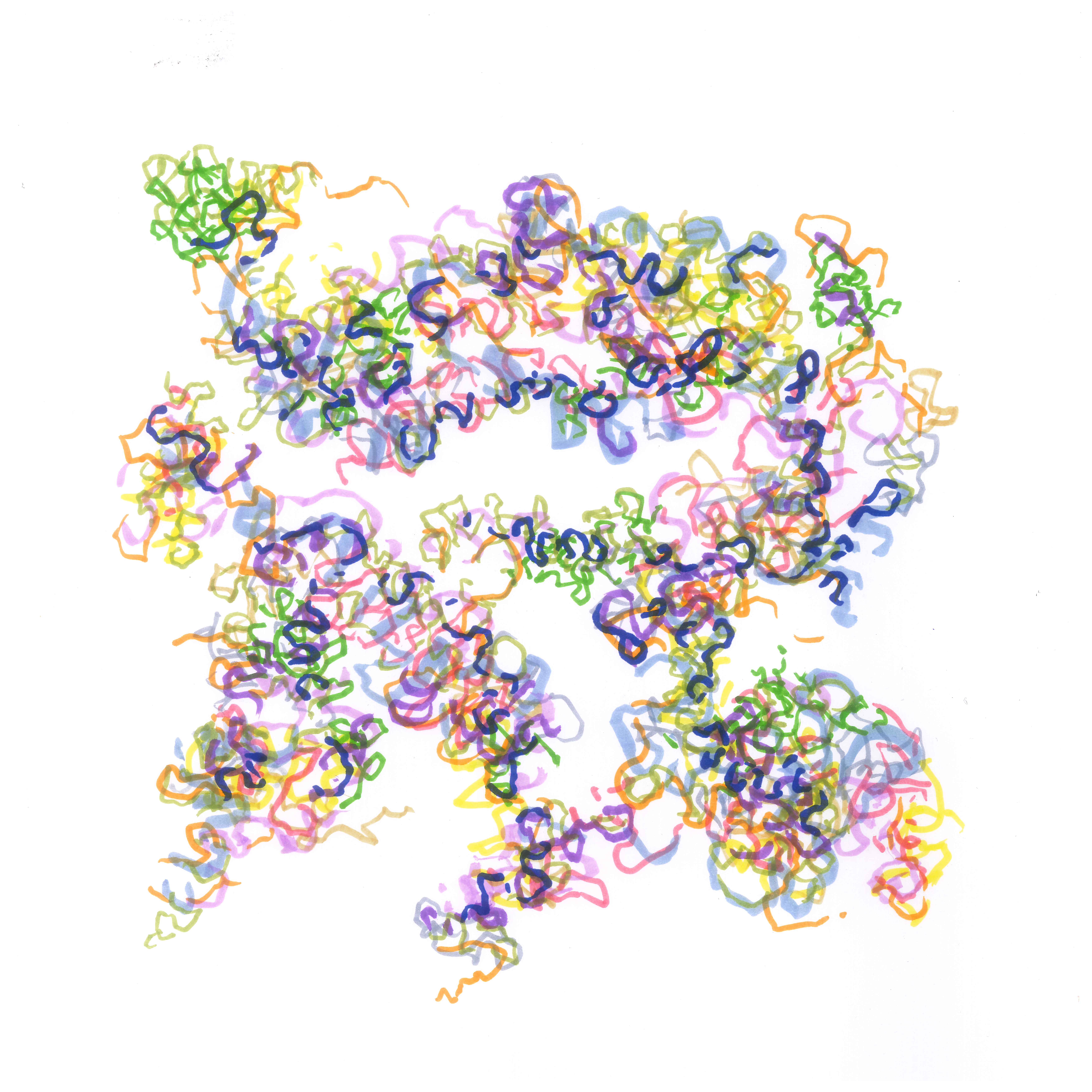

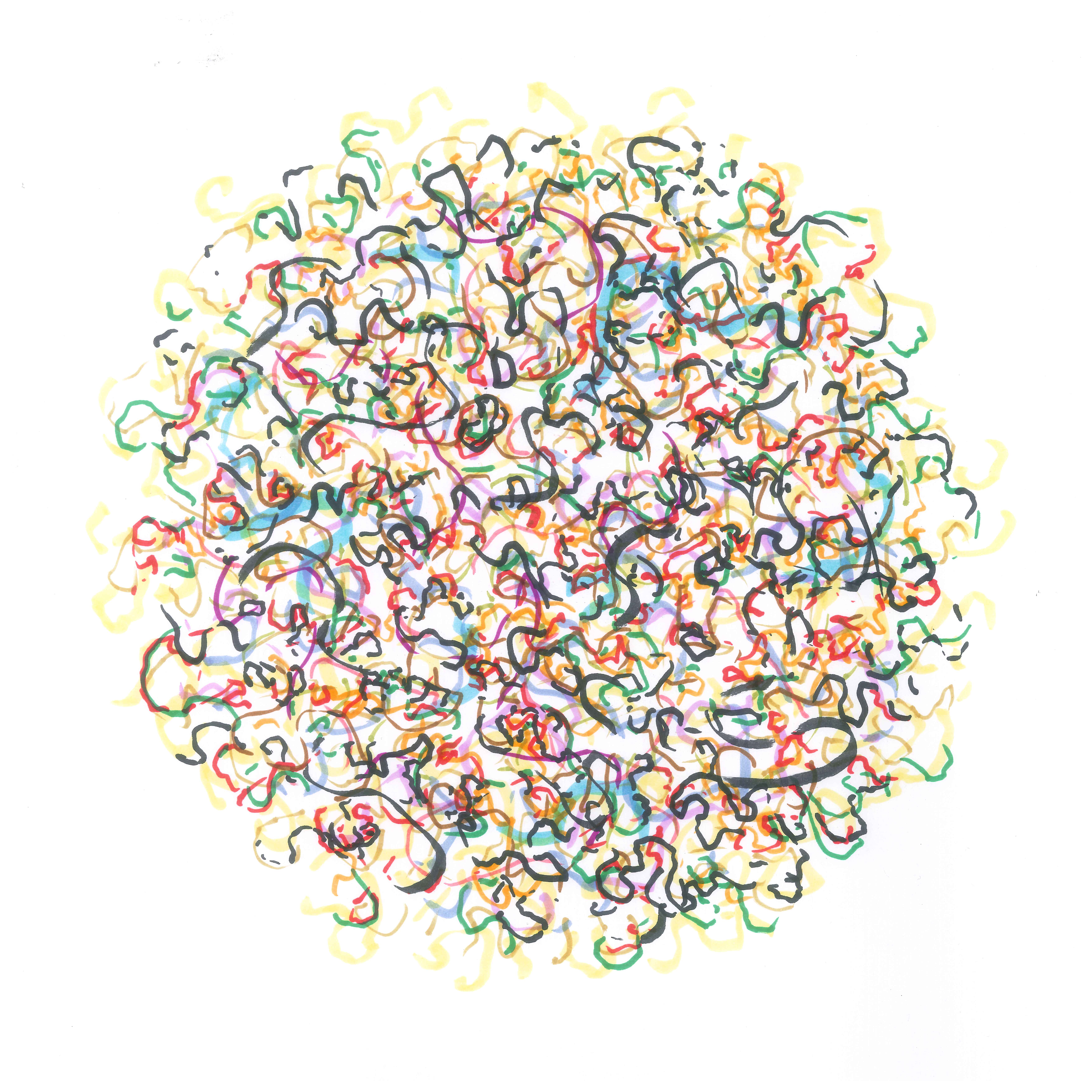

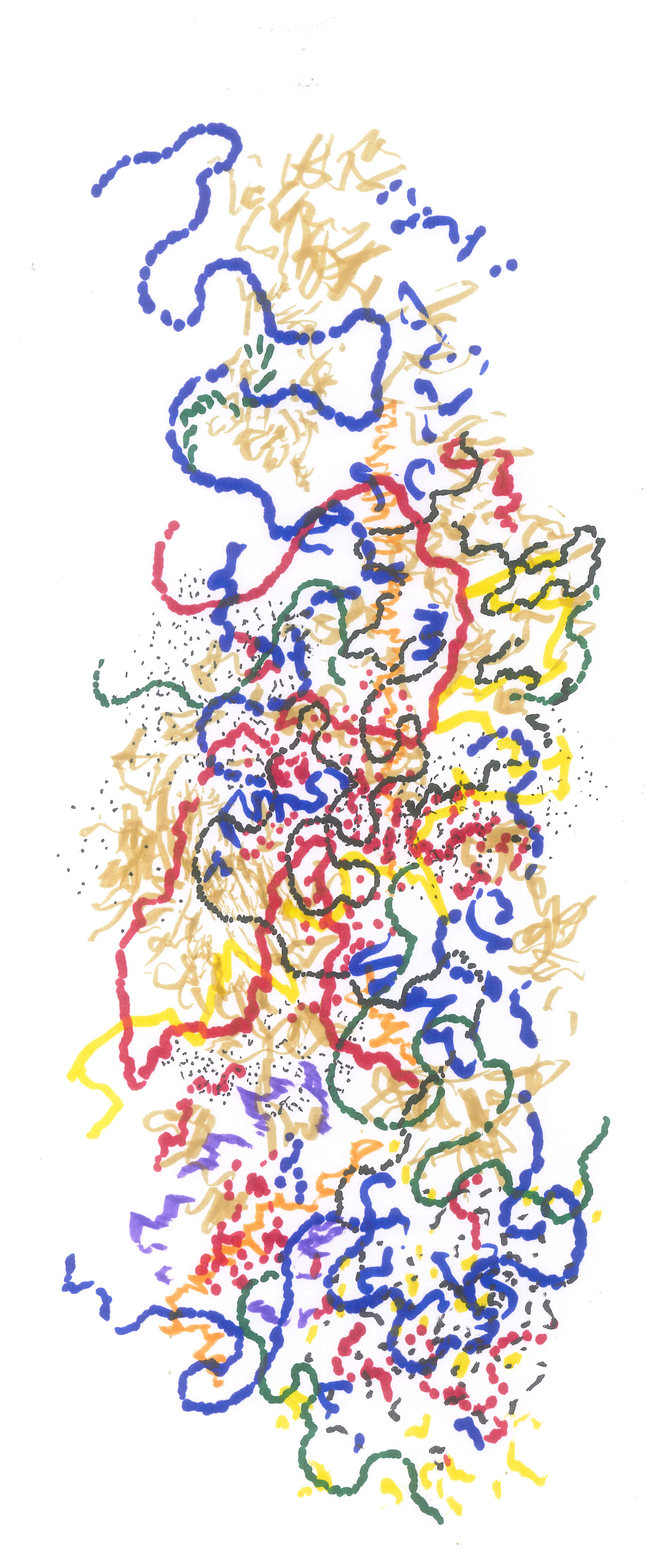

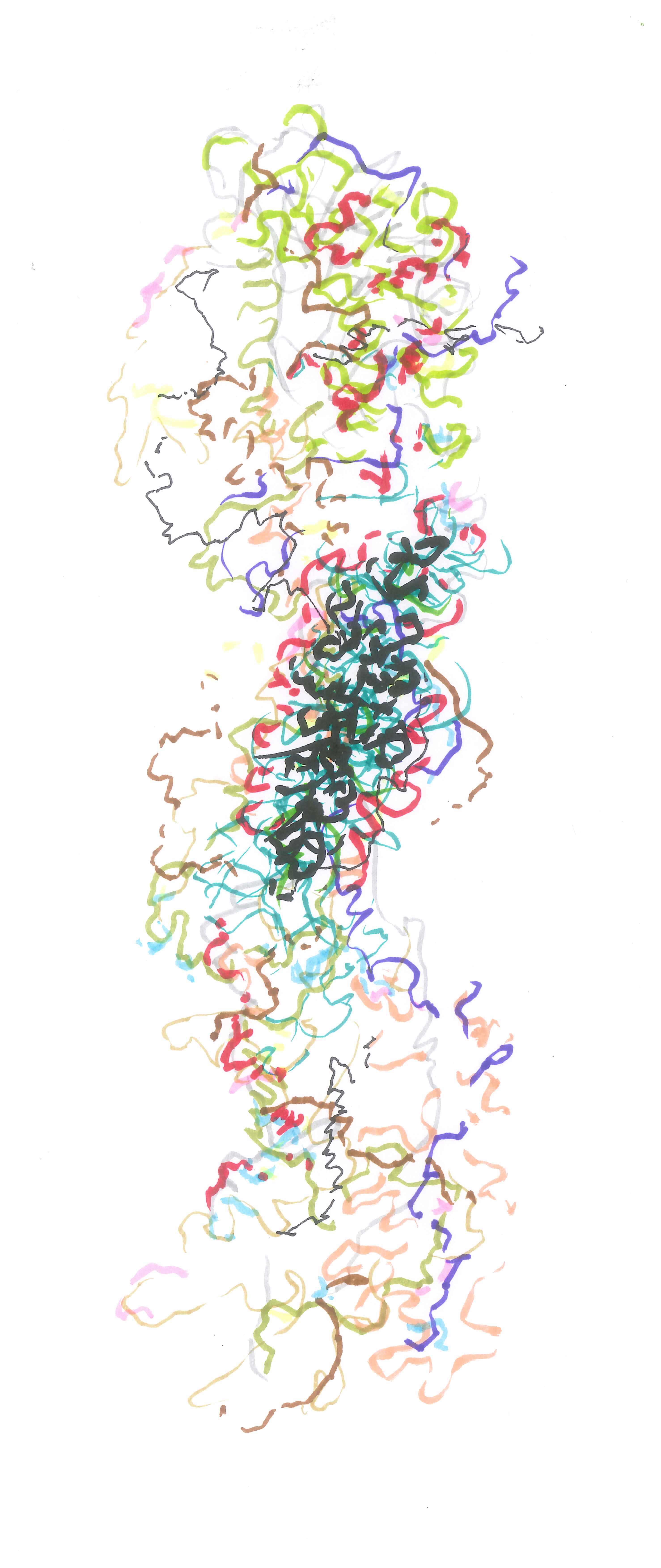

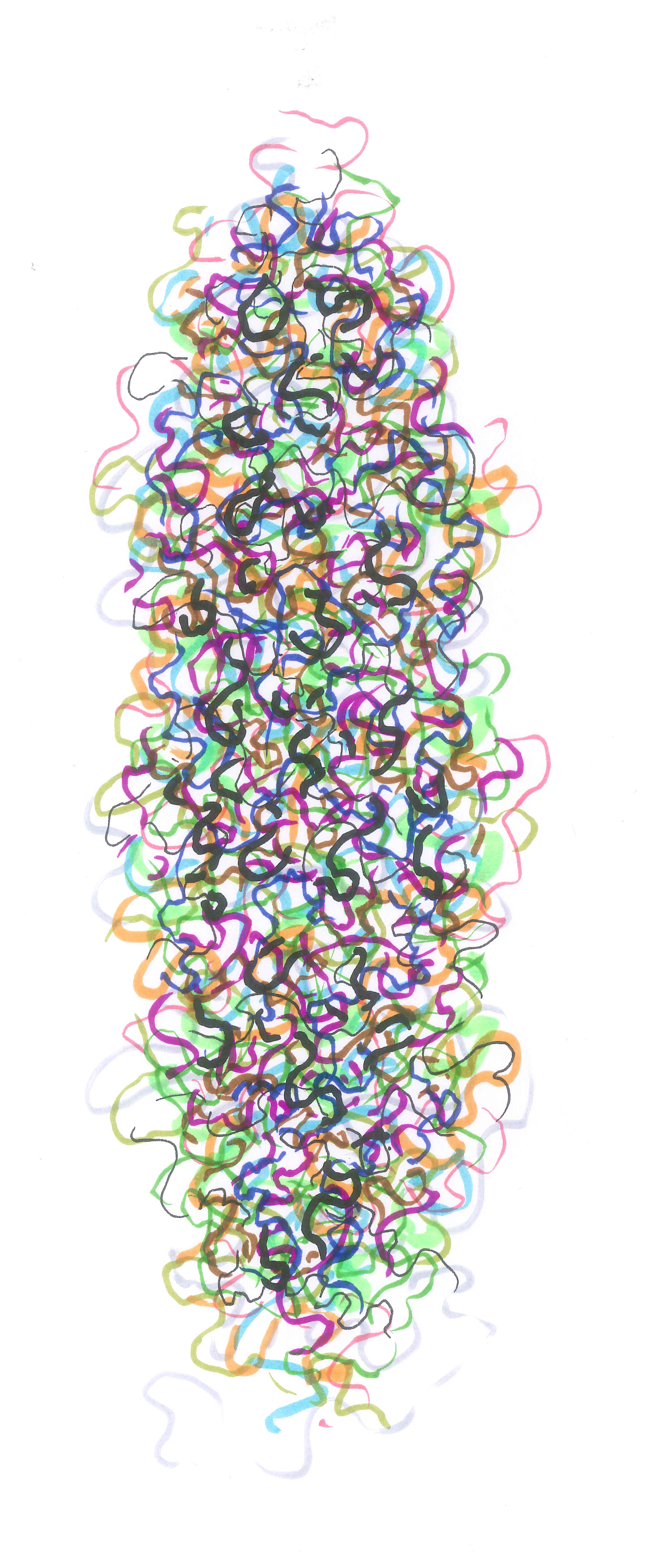

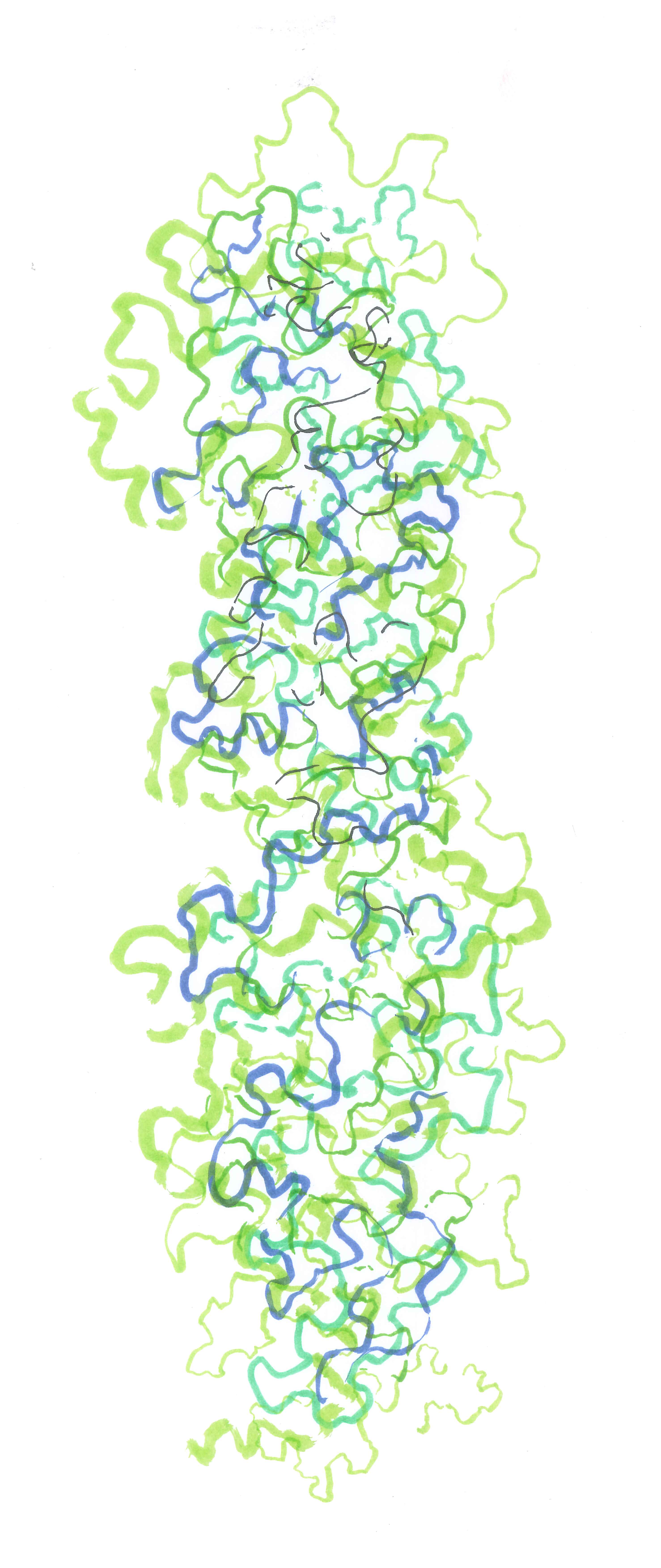

Take a look at my geometric picture series

Cubic view for comparison. It is essentially the same energy,

only in a different form.

Die ungegenständliche Malerei, also diejenige die ihre eigene Essenz erforscht, entfaltet sich zwischen den

zwei Extremen des geometrischen Formalismus und des Informel. Ersterer sucht die Essenz in der

ausgetüftelten Differenzierung der Proportionen, letzteres setzt auf die Unmittelbarkeit der ungefilterten

malerischen Geste. Das Informell will das Gemachtsein des Kunstwerks überwinden. Die Hand wird dabei

nicht vom kontrollierenden Auge geführt, sondern reagiert unmittelbar auf die Impulse einer inneren

Anspannung, die sich in nervösen Zuckungen entlädt. Das Auge wendet sich ab und die Hand wird

freigelassen, als wäre sie ein selbstständig denkendes Wesen.

Andererseits ist der Künstler immer und zuallererst ein kritischer Beobachter des eigenen kreativen Aktes.

Das, was das Bild am Ende kommuniziert, ist die Auswertung eines kontrollierten Vorgangs. Was die

freigelassene Hand bewerkstelligt muß also der Bewertung durch das Auge standhalten. Ansonsten

könnten wir uns auch mit Kinderzeichnungen begnügen und müssten die Unmittelbarkeit nicht durch ein

künstlerisches Verfahren erzeugen. Das Auge übernimmt die Redaktion: es bringt das Ganze auf einen

Zustand. Es entscheidet über die Wahl der Farben und Malwerkzeuge und es entscheidet an welchem

Punkt der Prozeß angehalten, und ob das Ergebnis freigegeben oder vernichtet wird.

Aber nach welchen Kriterien mischt es sich ein? Gibt es eine ästhetische Gesetzesgrundlage? In der

geometrischen Abstraktion gibt es sie. Die Maße werden abgewogen. Es gibt immer eine Begründung, für

jedes Maß und für jeden Farbton. Und dieses Formgesetz ist das, was das nicht repräsentierende Bild

repräsentiert. Im Informell dagegen wird gerade dieser Schritt übersprungen. Das Auge muß nach eigenem

Gespür entscheiden. Und dieses Gespür muß trainiert werden. Es ist ähnlich, wie etwa beim Aufhängen

eines Bildes. Die meißten Menschen haben ein Gespür dafür, ob es an der richtigen Stelle hängt, oder

vielleicht doch eher einen halben Zentimeter höher, oder einen Tick nach links bewegt werden soll. Und im

Alltag haben wir ein unbewußtes Gespür dafür wo wir Dinge platzieren, und wie wir uns in einem Raum

bewegen. Das ist eine Frage der Sensibilität. Wir spüren, wenn etwas an der falschen Stelle ist. Und genau

dieses Gespür ist es mit dem der Künstler ein Objekt gestaltet. Nur hier läuft es bewußt ab. Manchmal

entscheidet man sich gerade gegen den unmittelbaren Impuls. Man platziert absichtlich etwas an der

falschen Stelle, und guckt was passiert.

Am Ende muß natürlich Gleichgewicht hergestellt werden, in welcher Form auch immer. Die Spannungen

müssen konzentriert werden. Es gibt ein Gleichgewicht im Ungleichgewicht, und eine Unruhe im in sich

Ruhenden. Diese Spannungsverhältnisse bilden das Repertoire der Ausdrucksmöglichkeiten. Das gilt für die

geometrische Abstraktion genau so. Die Verhältnisse von Beobachtung und Aktion sind dort anders, aber

der künstlerische Ausdruck ist davon unabhängig. Wenn es um die Essenz der Kunst geht, können wir uns

nicht am Stilistischen festhalten. Das, was sich ausdrückt, was zur Oberfläche, sich in die Form hinein

drängt, ist immer dasselbe. In Ermangelung eines besseren Begriffs will ich es 'Schöpfungsdrang' nennen.

Malerei als Malerei oder Kunst als Kunst ist immer der Versuch eines Künstlers den inneren Drang auf eine

wahrnehmbare Form zu bringen; möglichst ohne etwas wegzulassen oder hinzuzufügen. Das ist es, was

man 'Innere Notwendigkeit' nennt.

Schauen Sie sich zum Vergleich meine geometrische Bildserie

Cubic view an. Es ist essentiell die gleiche

Energie, nur in einer anderen Form.