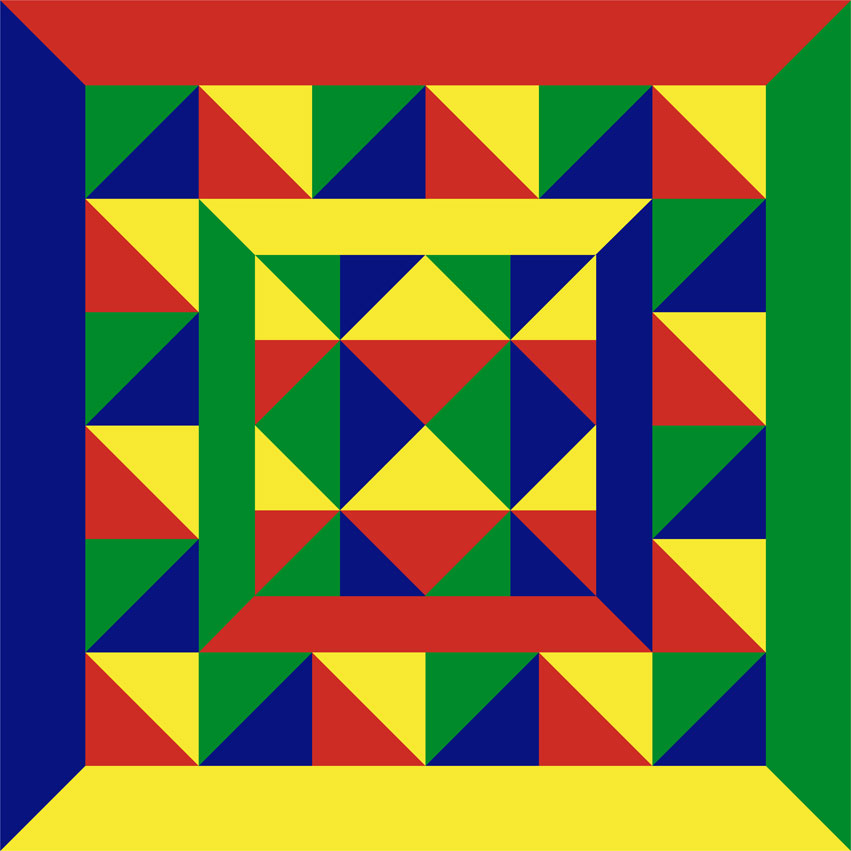

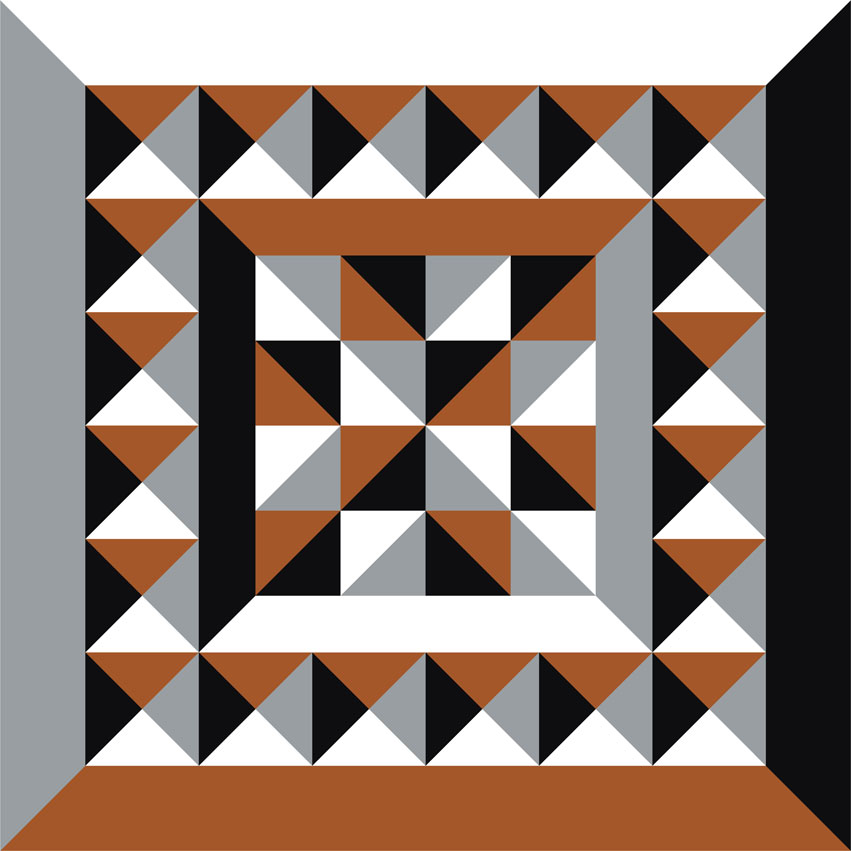

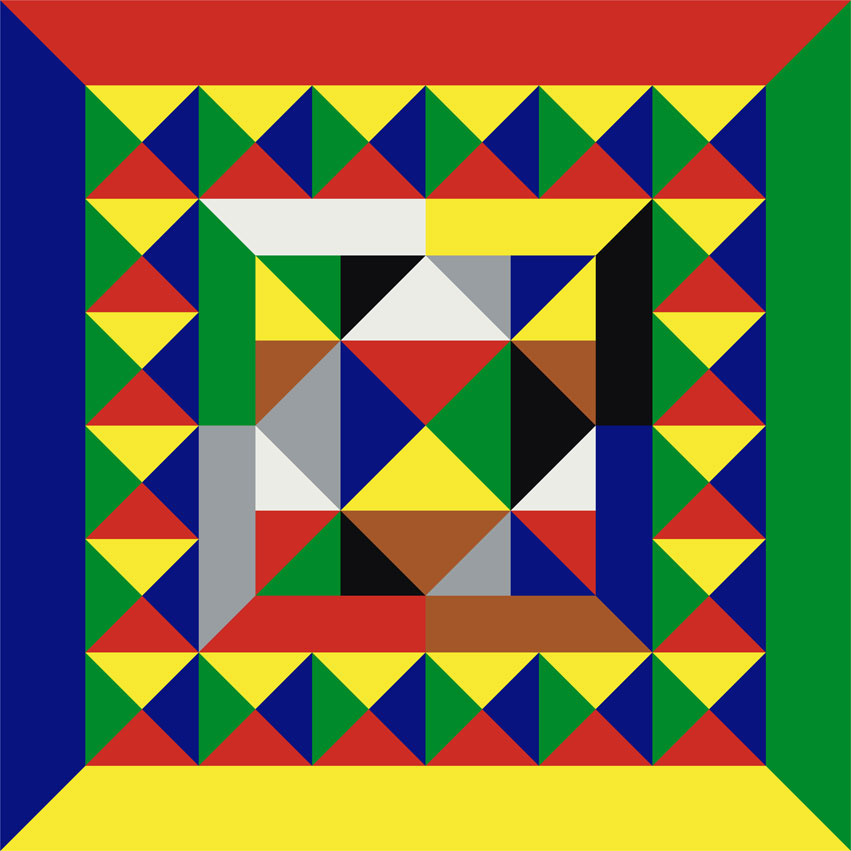

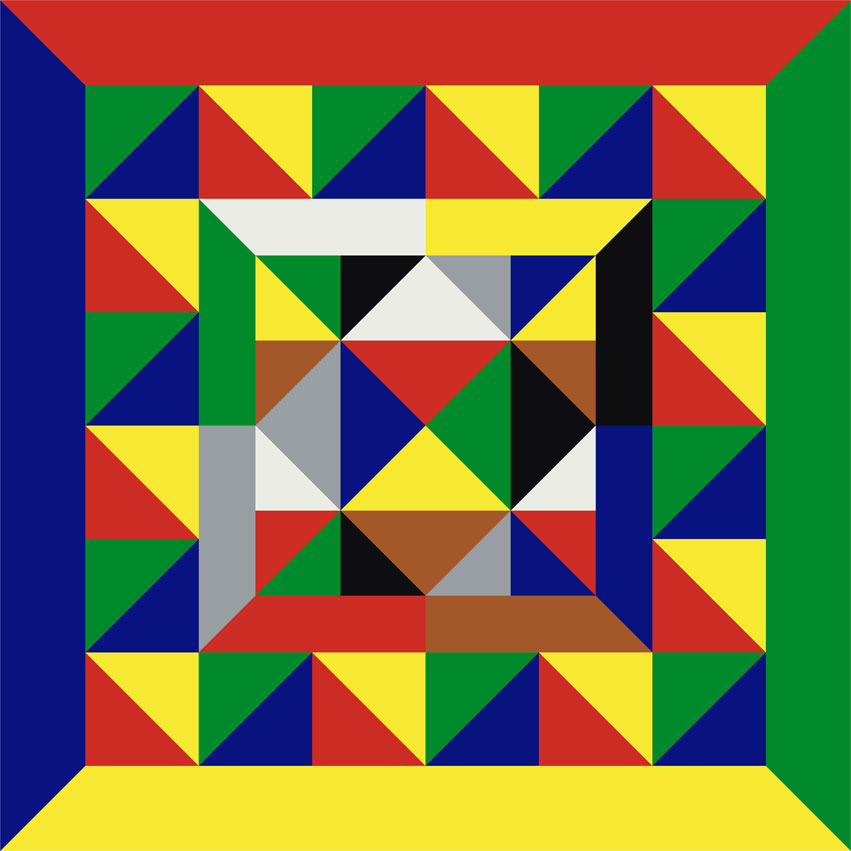

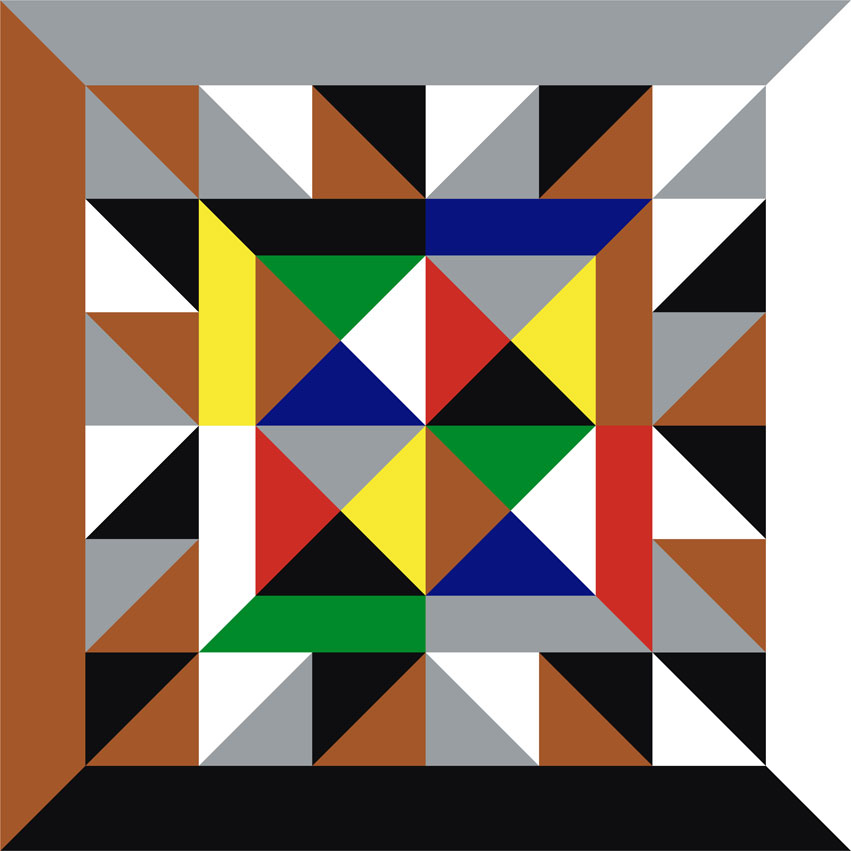

Die Maxime der konstruktivistischen Malerei war das Vermeiden von illusionistischer Raumtiefe. Beim

Kubismus, der ein Übergangsstadium zwischen gegenstandsbezogener und reiner Abstraktion markiert,

wird dagegen die Dreidimensionalität in einem gewissen Maß konserviert; wenn auch nicht im

naturalistischen Sinne. Der kubistische Raum ist ein irrationaler Raum, wo ein Objekt aus verschiedenen

Perspektiven gleichzeitig betrachtet wird.

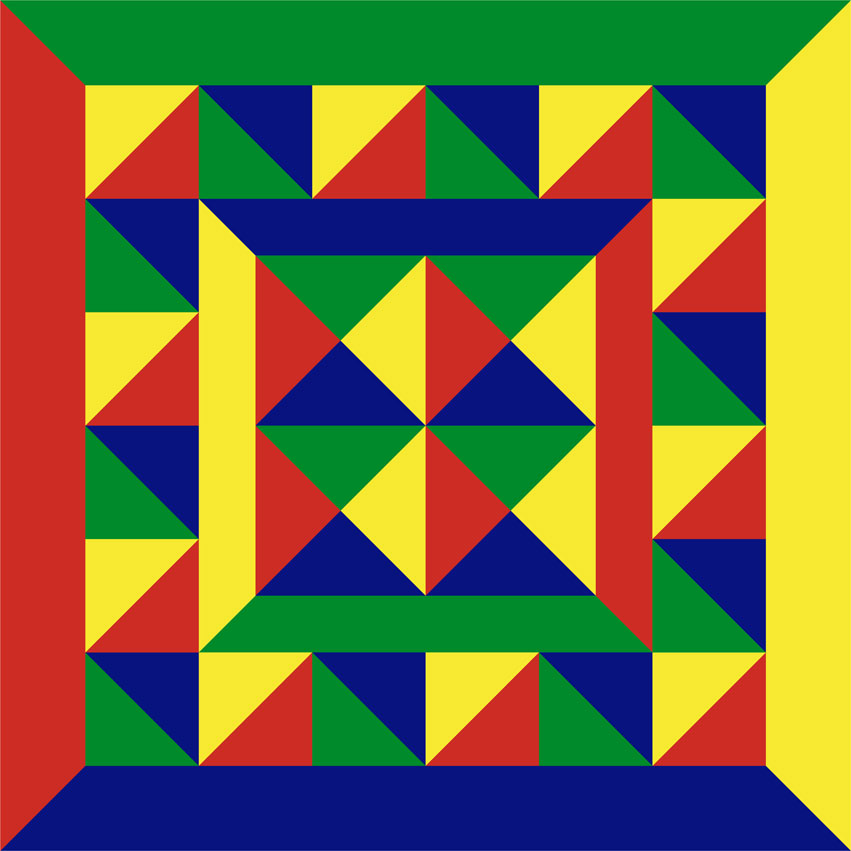

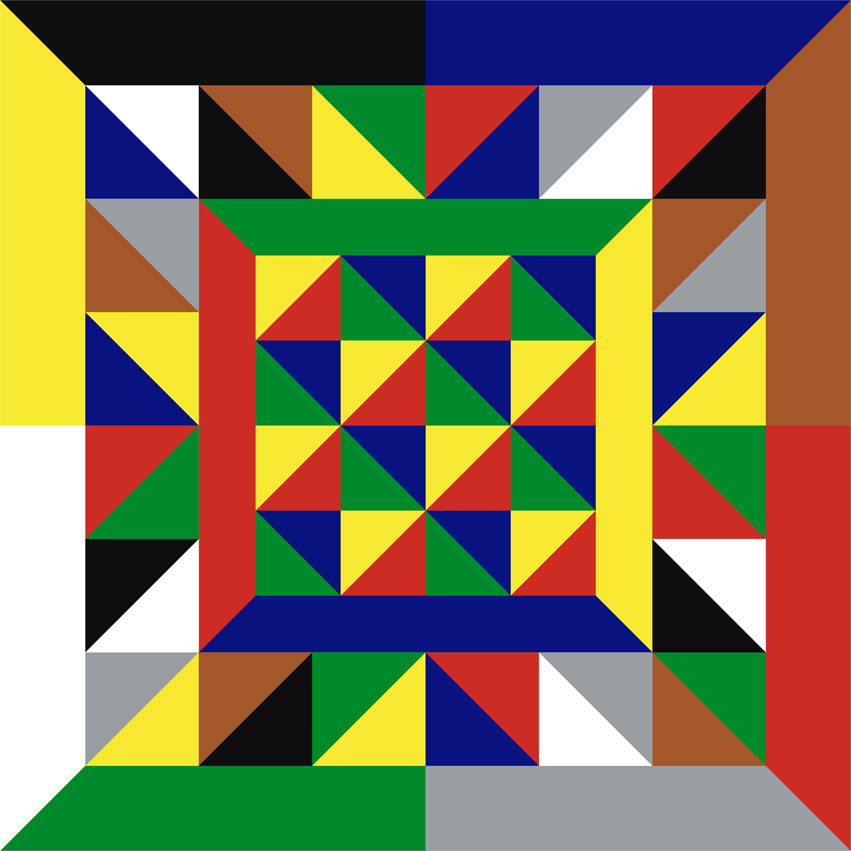

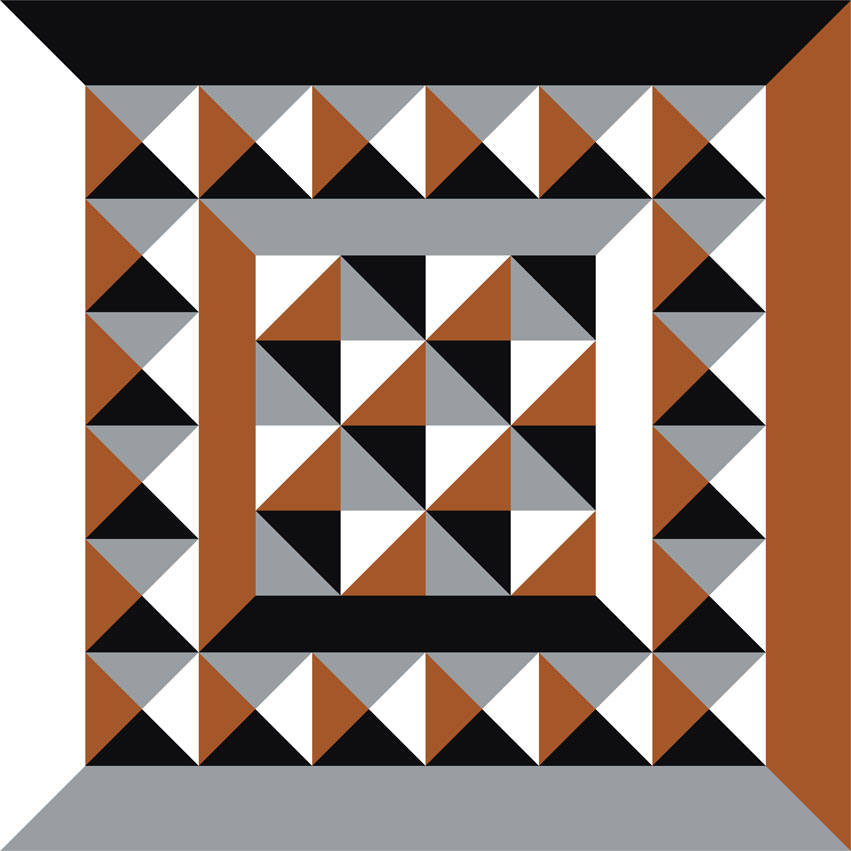

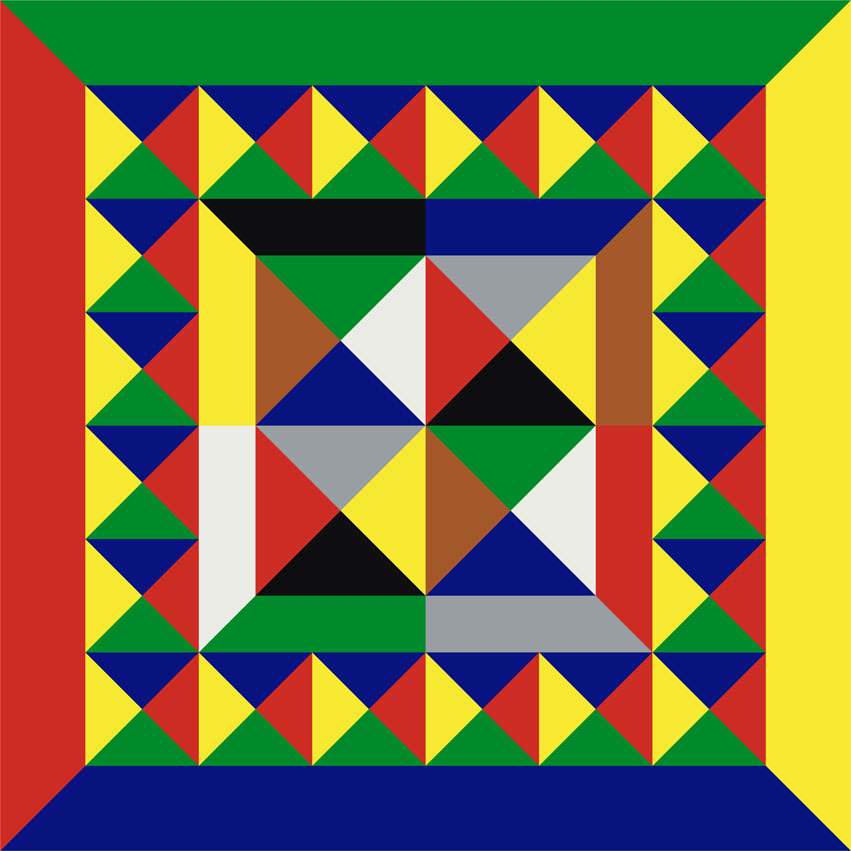

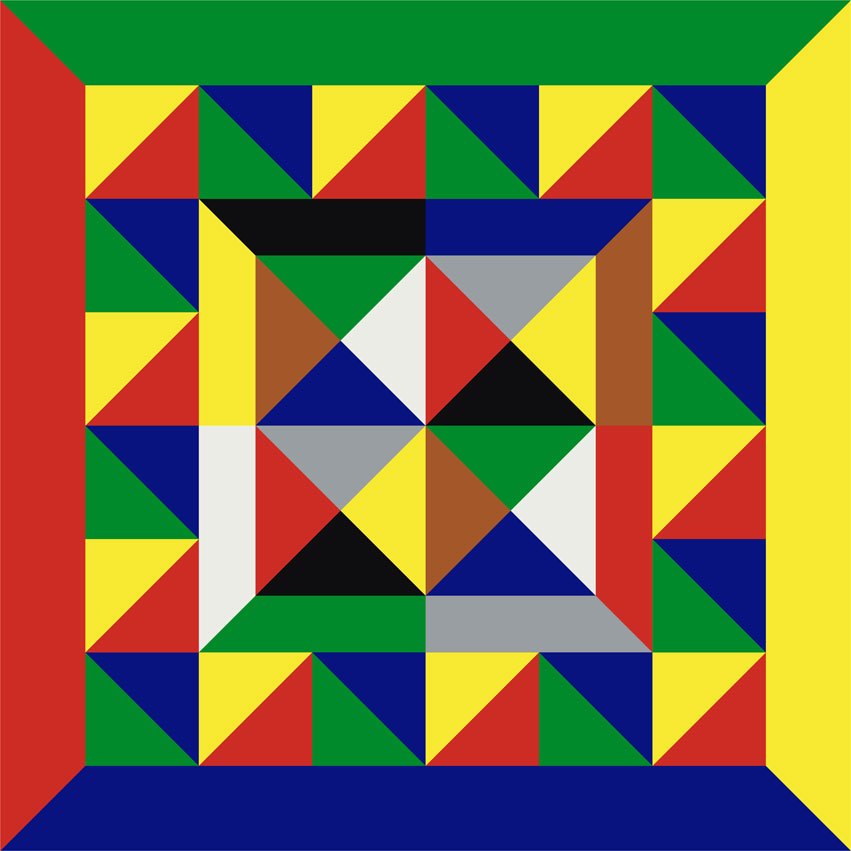

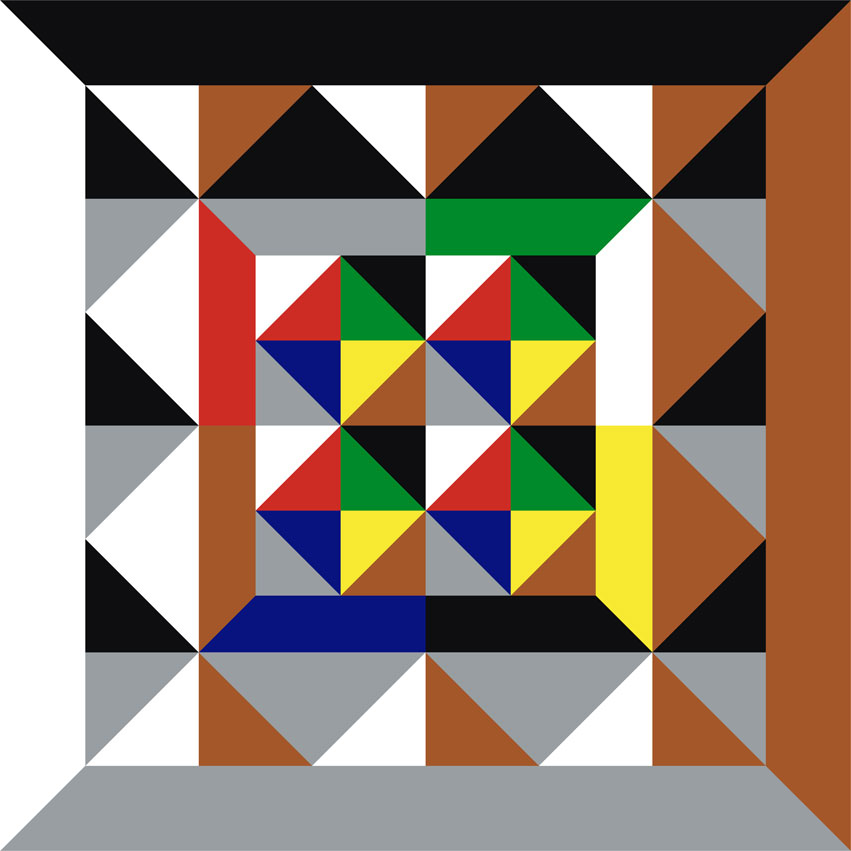

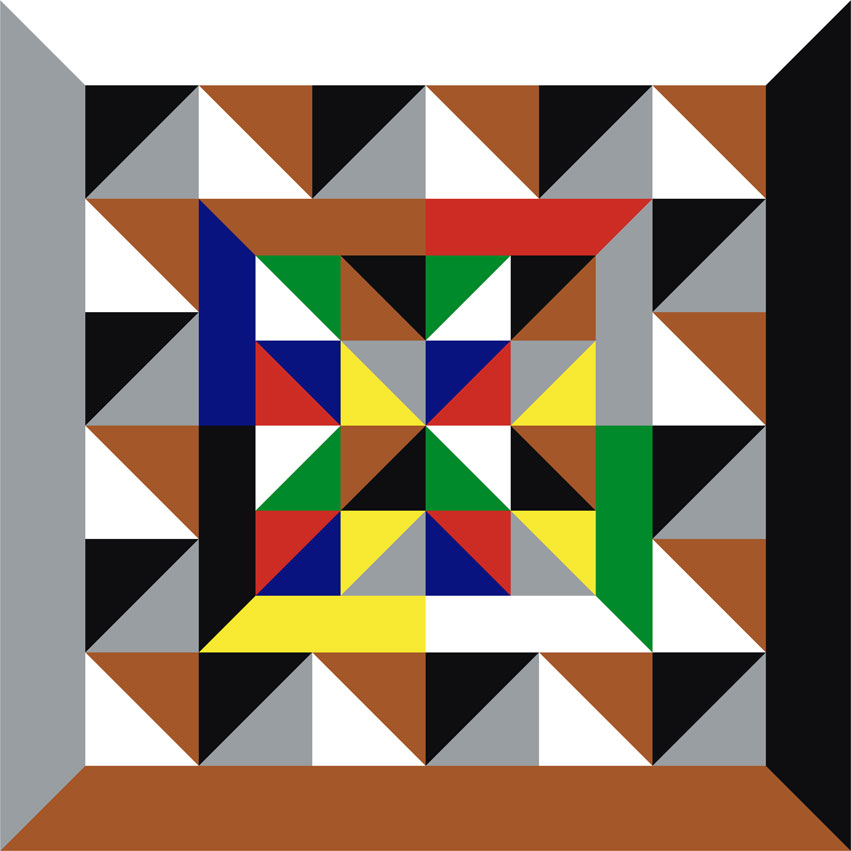

Raumtiefe wird in der Malerei hauptsächlich durch Fluchtlinien erzeugt; eine Diagonale im Bild erzeugt

unwillkürlich einen 3D Effekt, auch dort wo sie eine bloß ornamentale Funktion hat. Deshalb war die

Diagonale in der neoplastizistischen Malerei verboten. Für den Kubismus wiederum war sie, in ihrer

Funktion als Schnittkante zwischen verschiedenen Bildebenen, ein elementares Stilmittel.

Aus irgendeinem Grund sind die Kubisten niemals zur reinen Abstraktion vorgedrungen; als sei der

Bezug zur Dingwelt eine Bedingung des Verfahrens. Die abstrakten Puristen, auf der anderen Seite,

haben sich nie auf die kubistische Konzeption eines mehrperspektivischen Bildraumes eingelassen; die

reine geometrische Abstraktion blieb dem Credo der Flachheit verpflichtet.

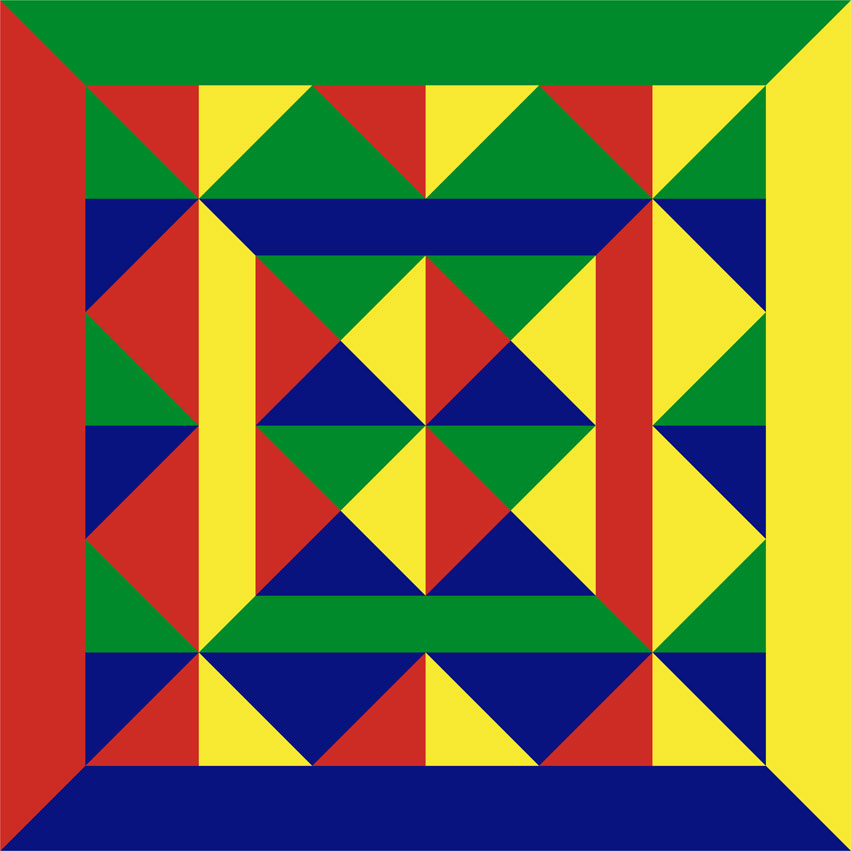

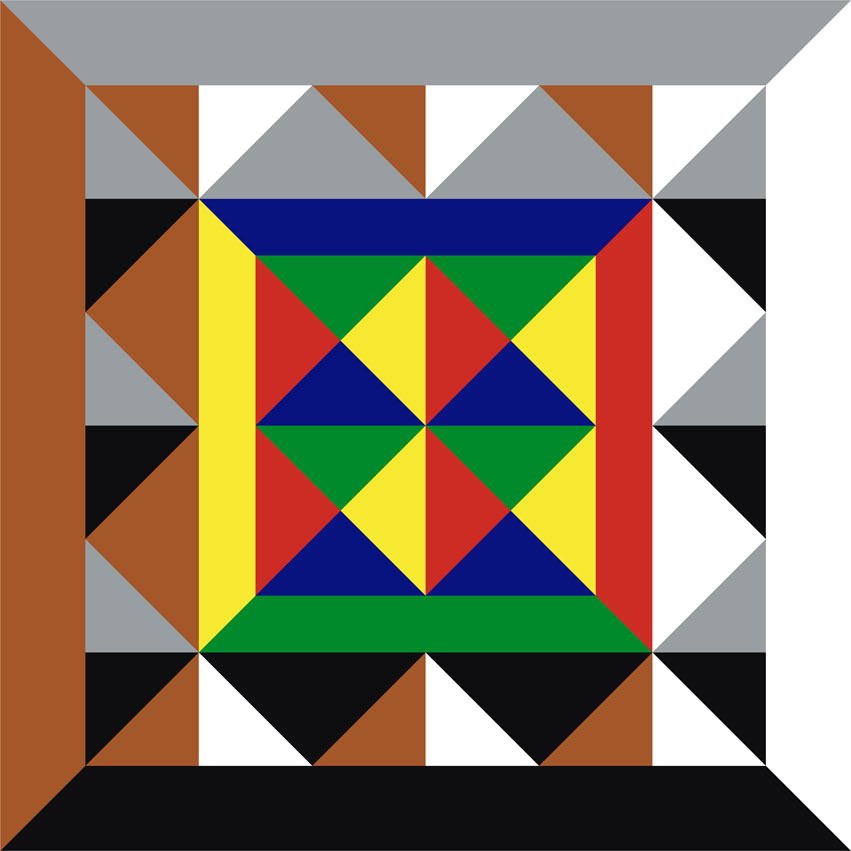

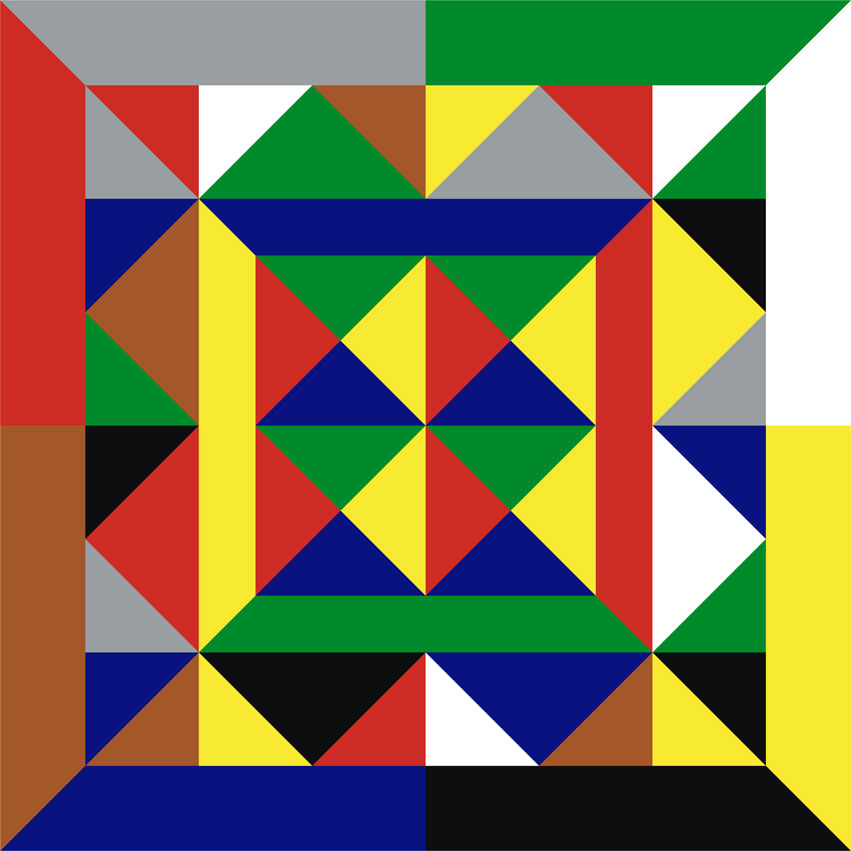

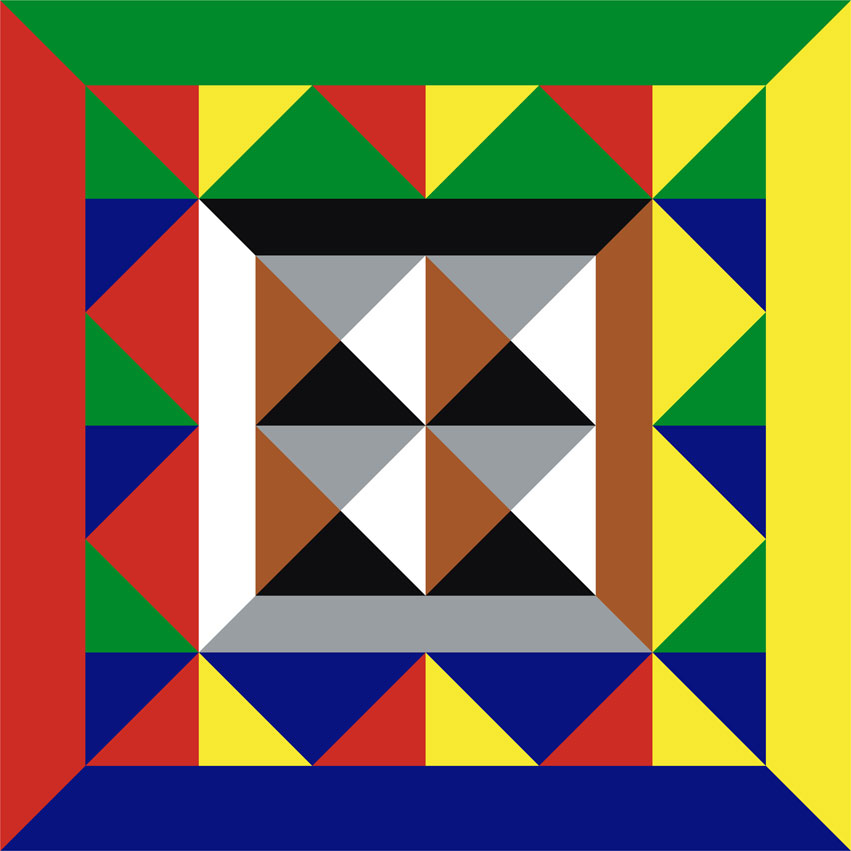

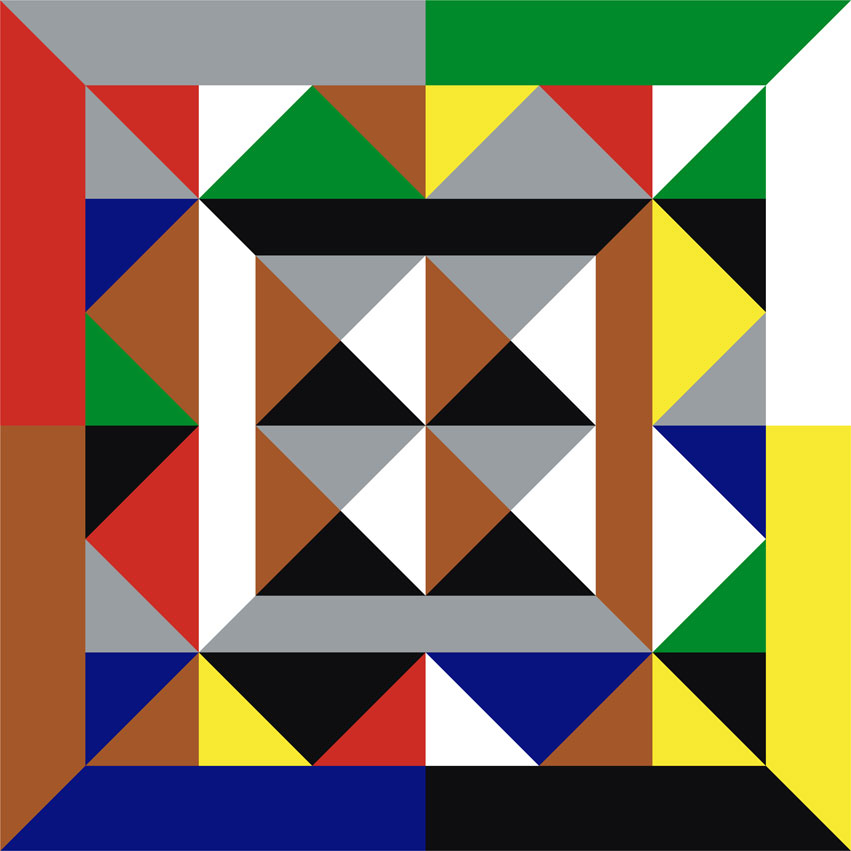

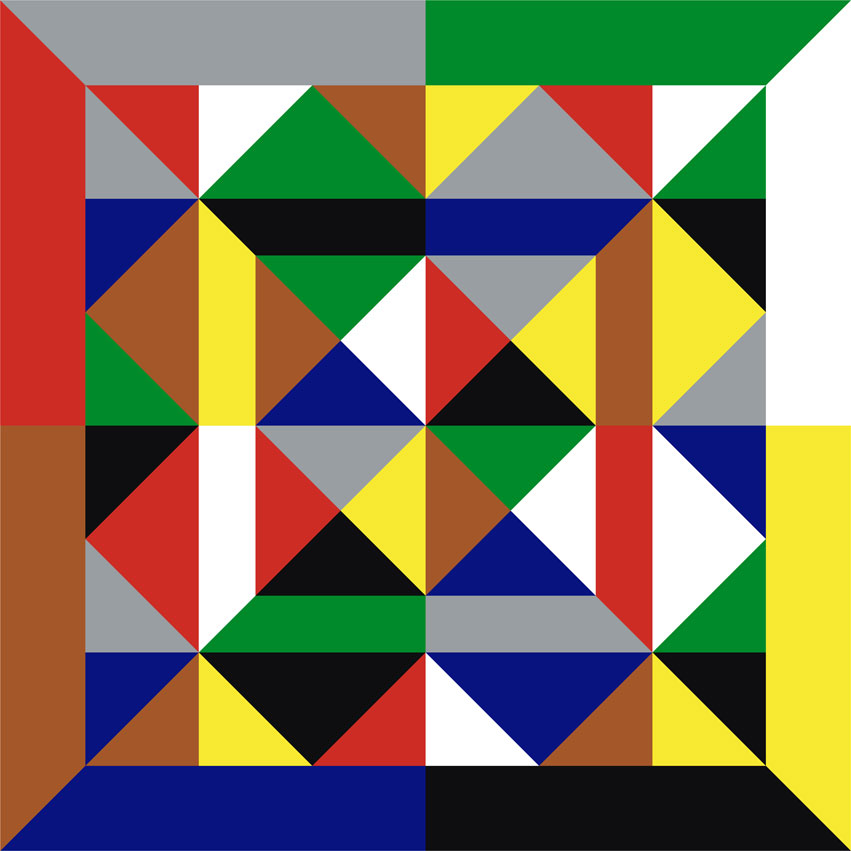

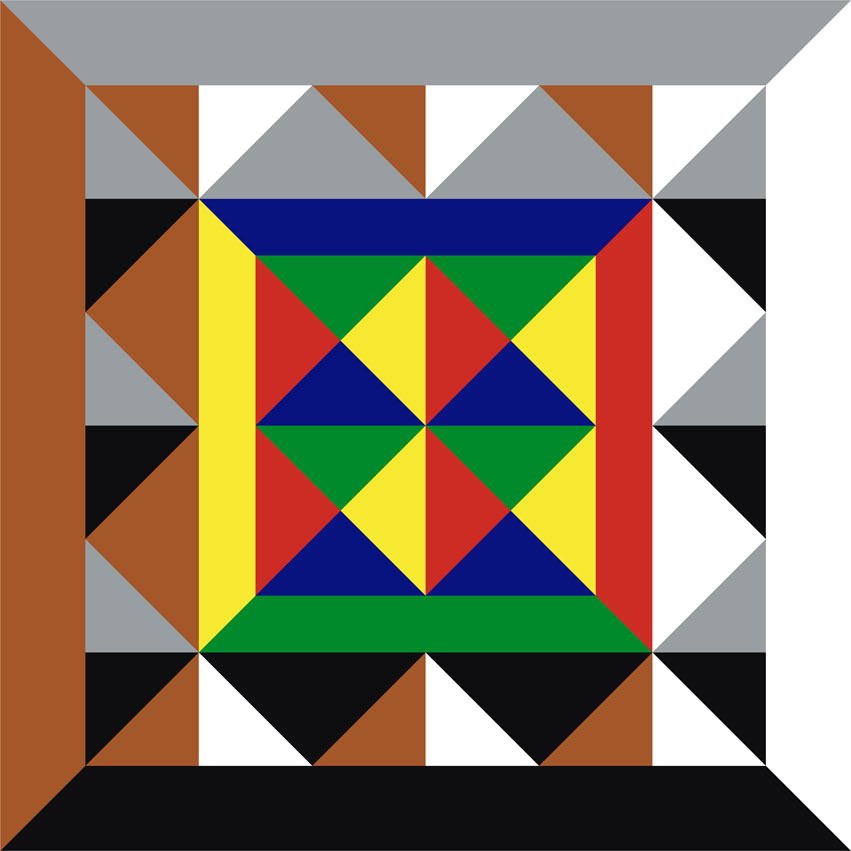

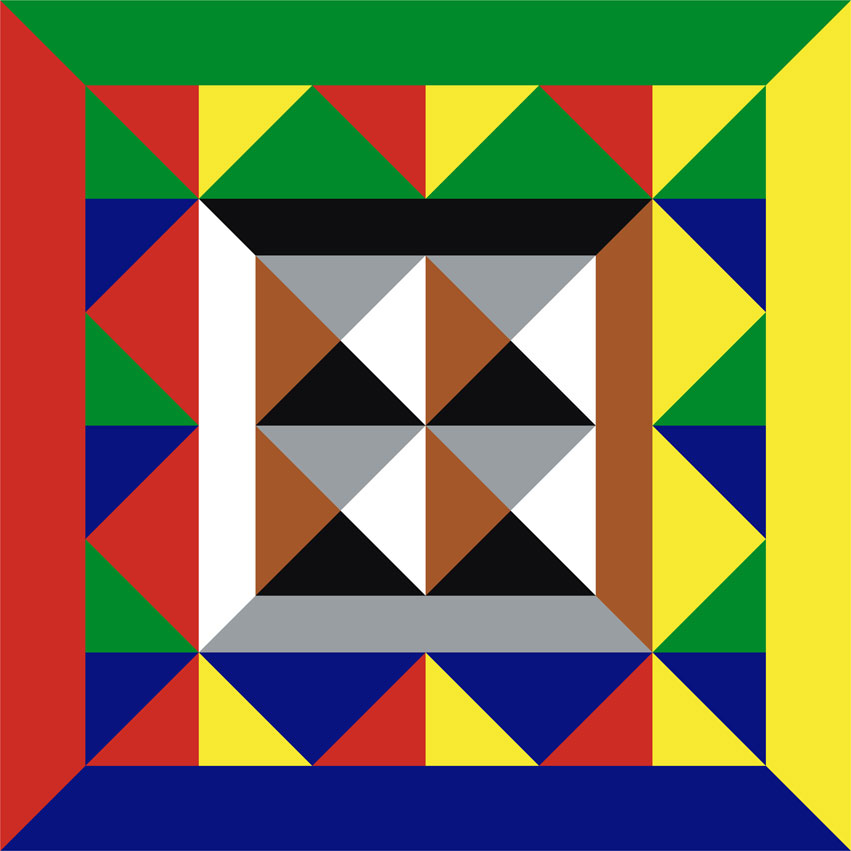

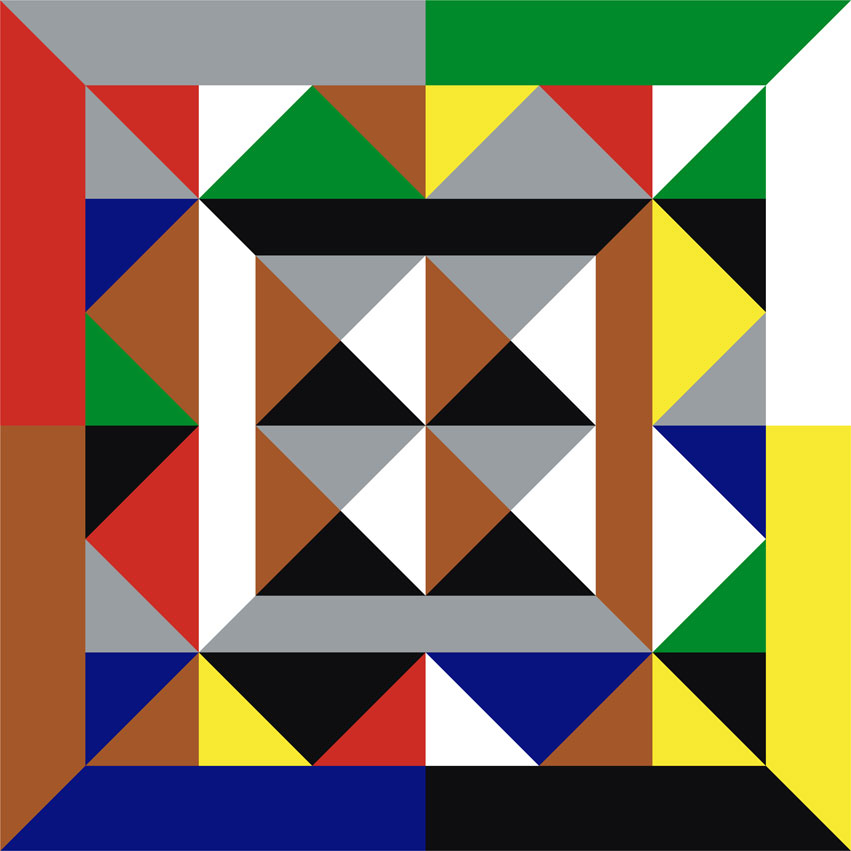

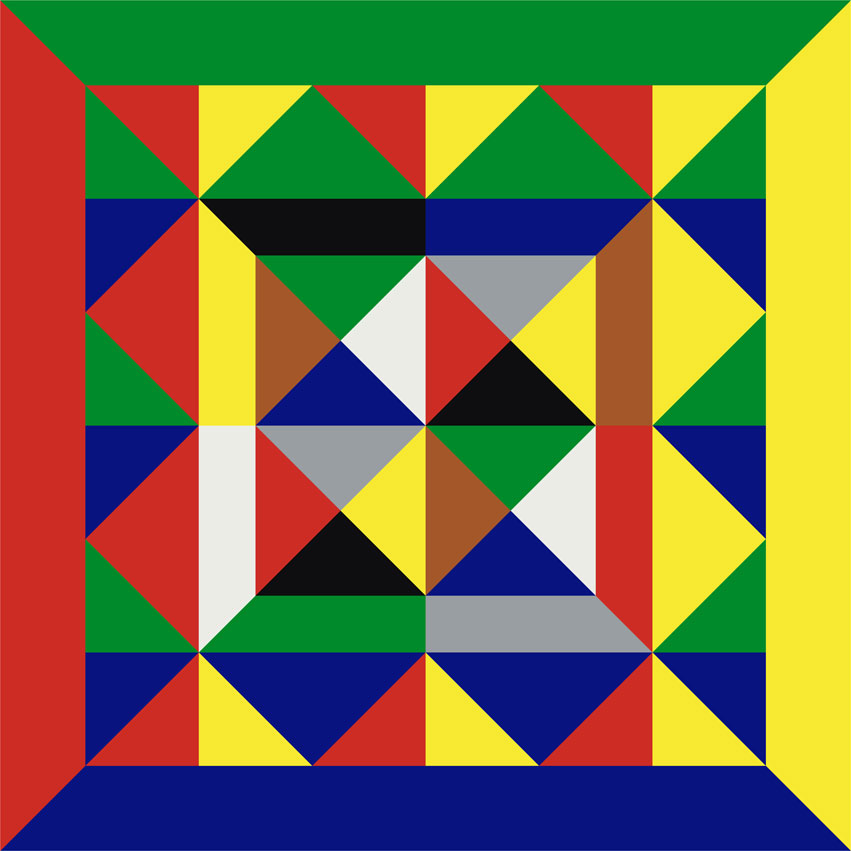

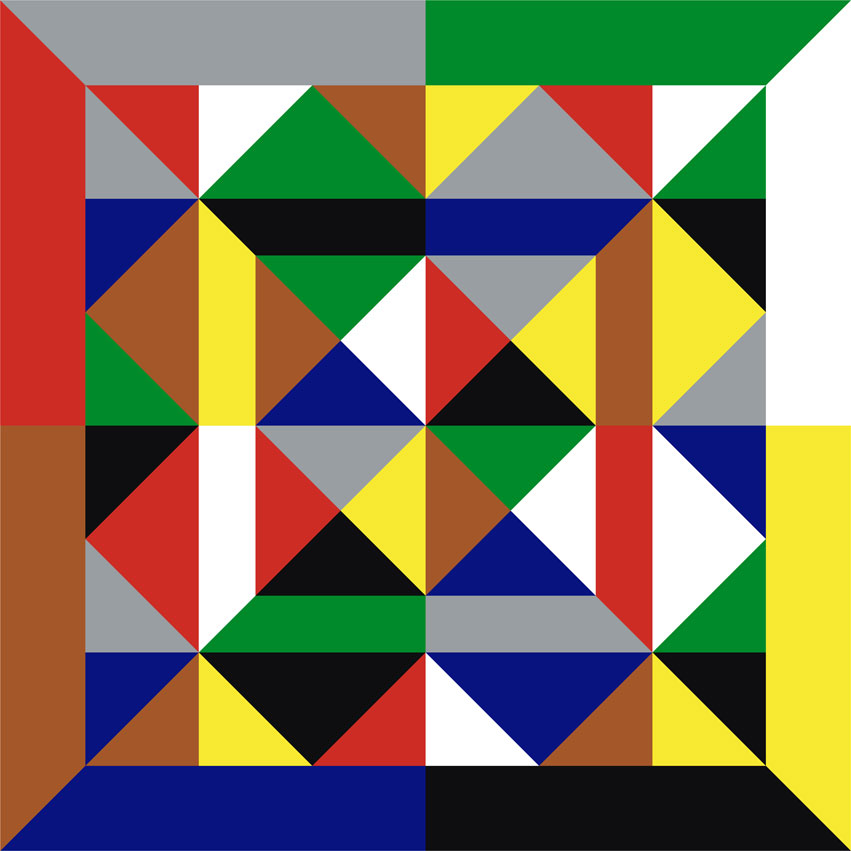

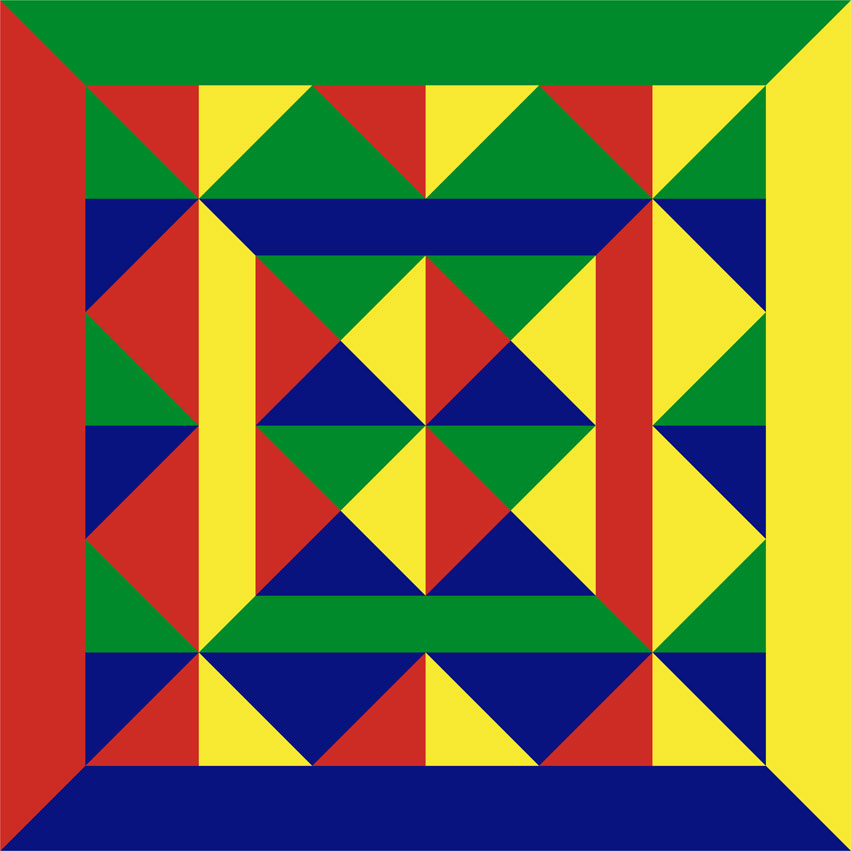

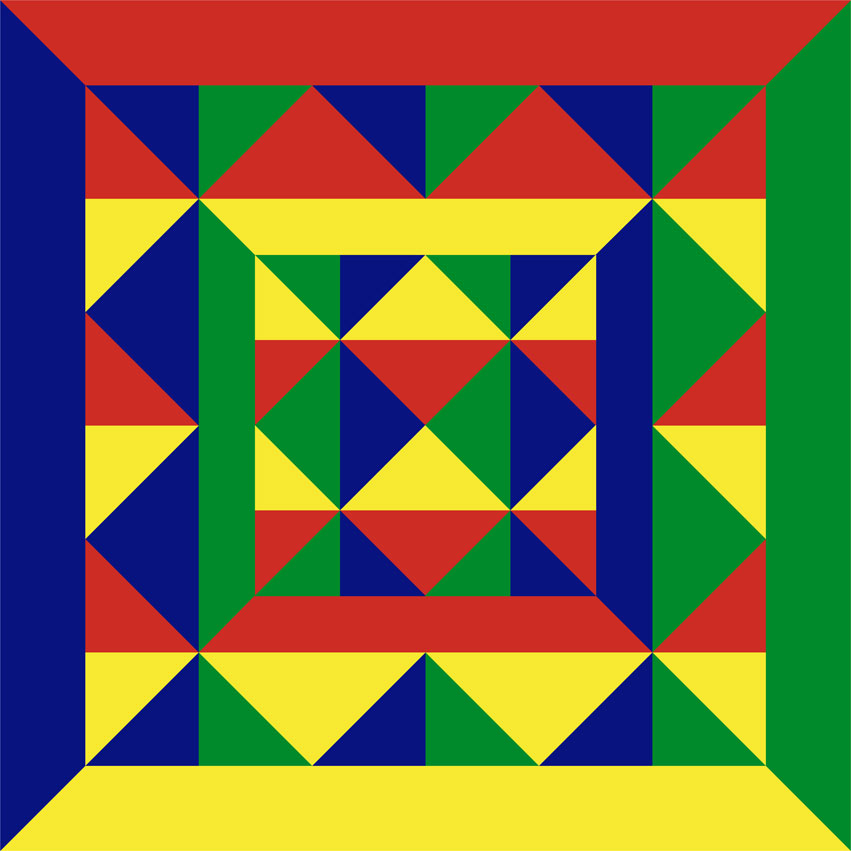

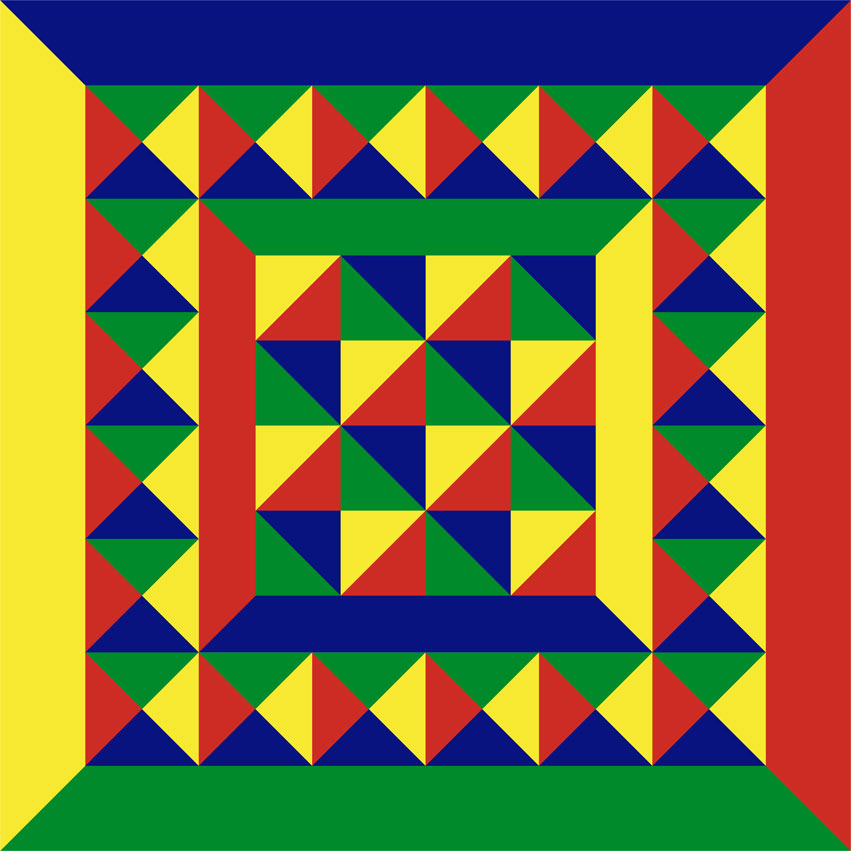

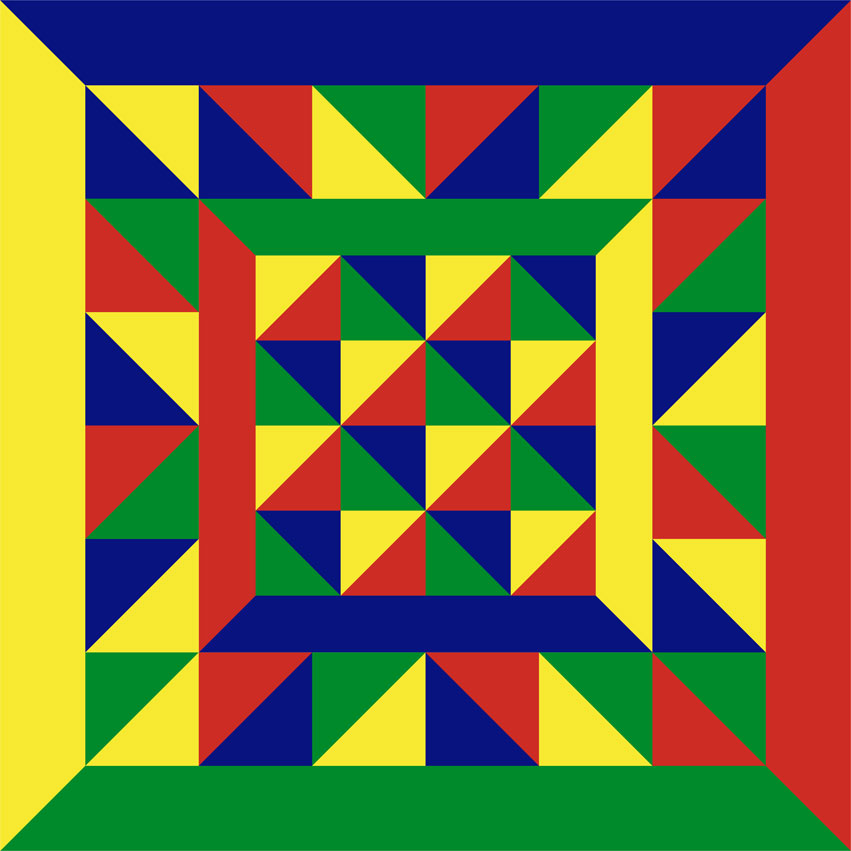

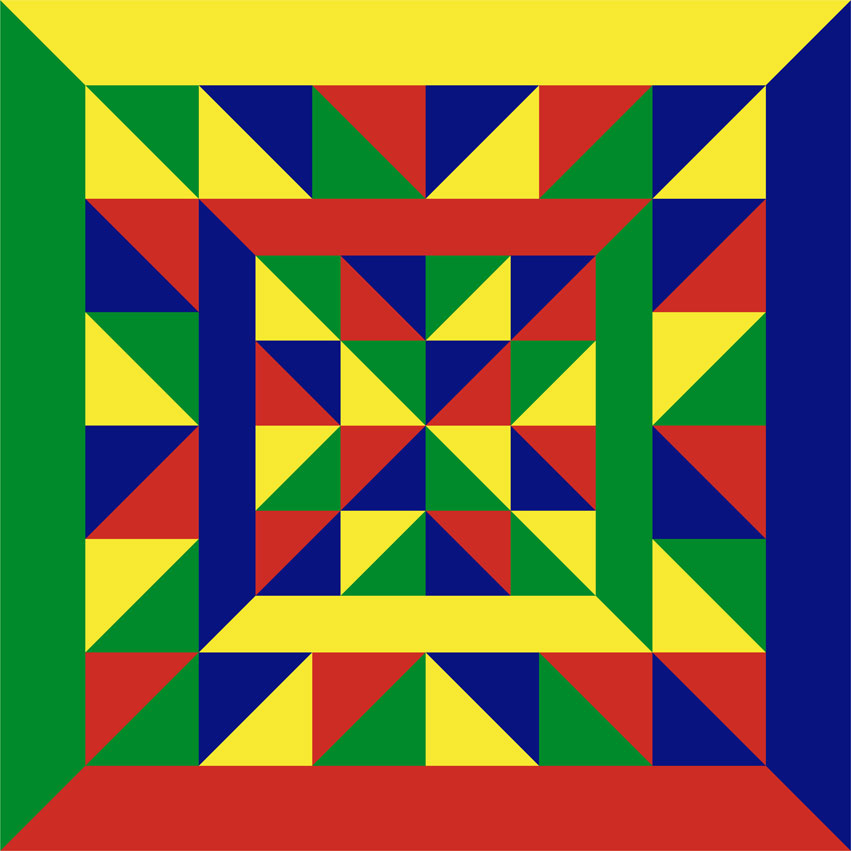

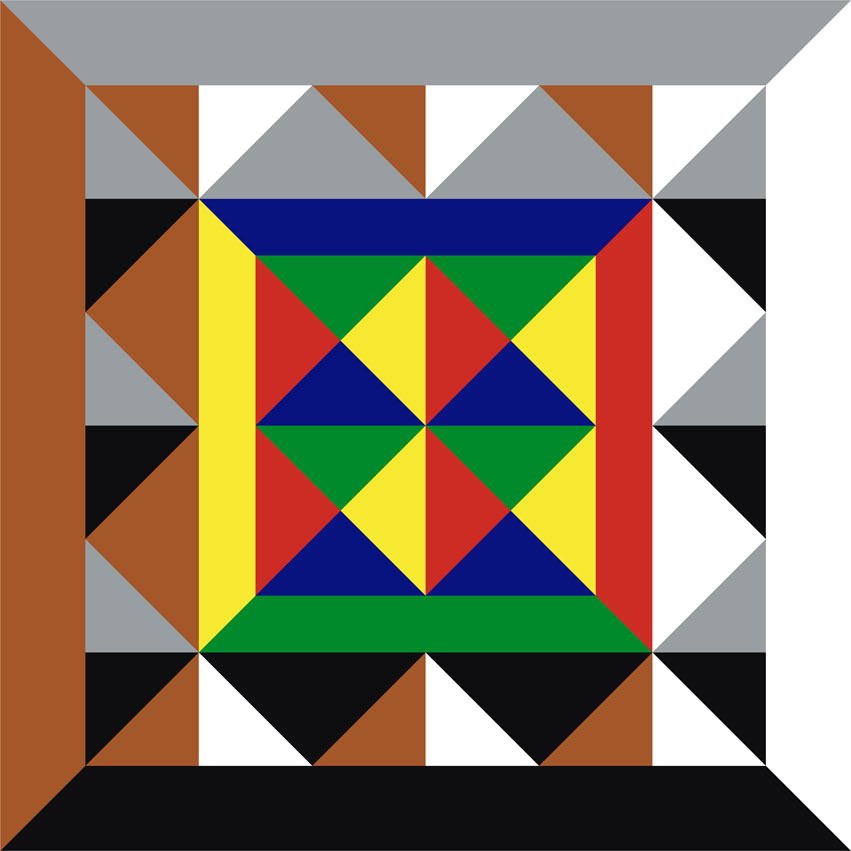

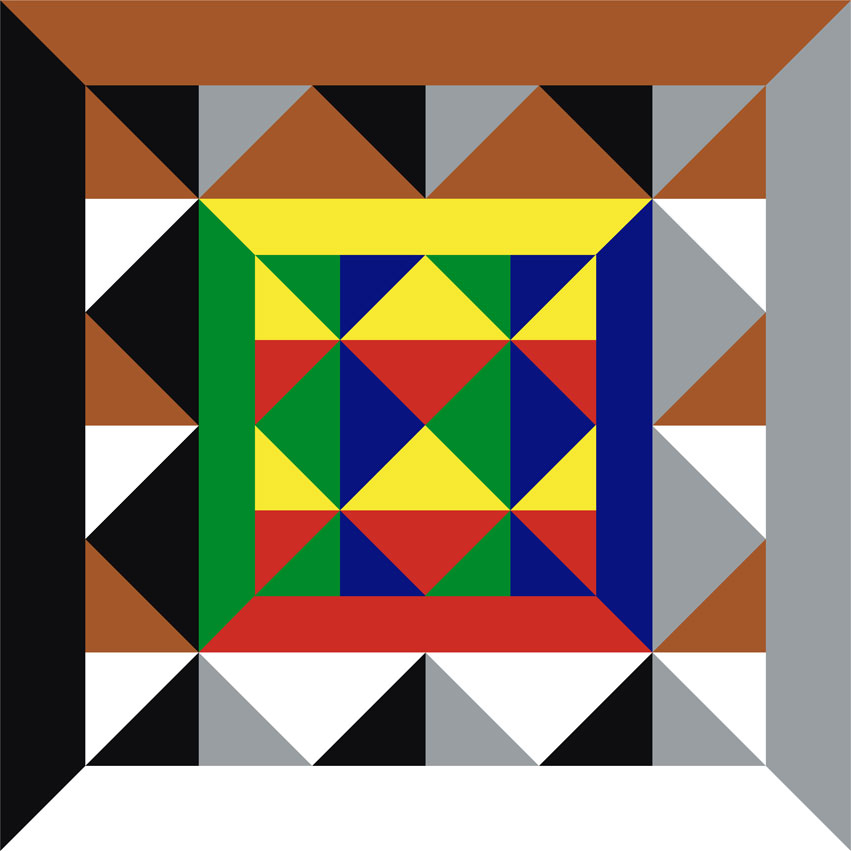

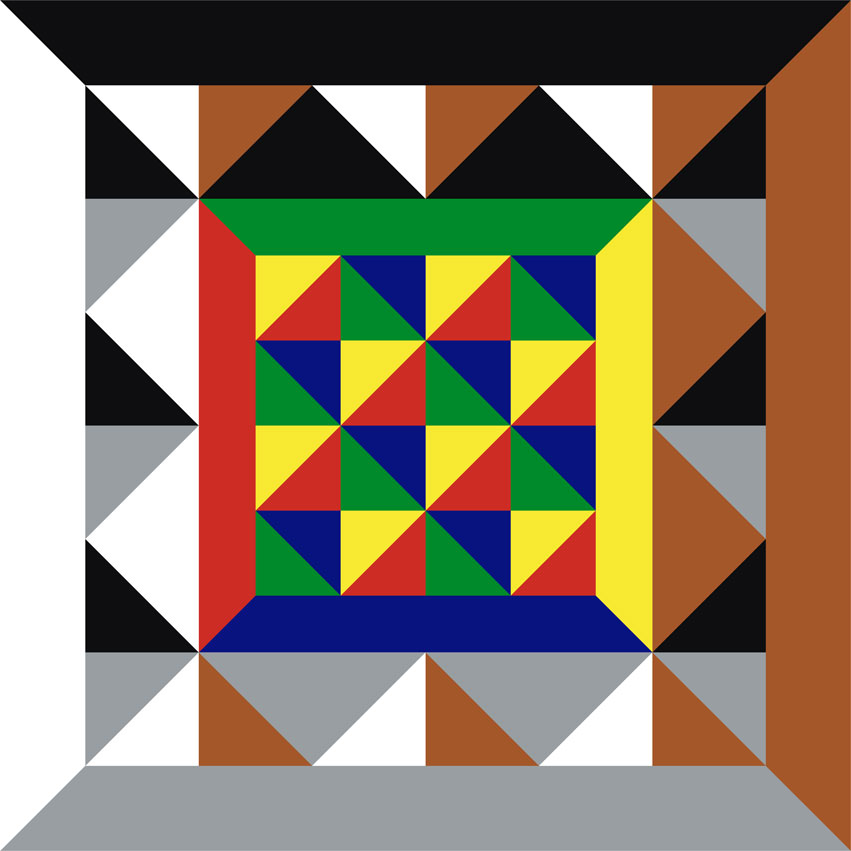

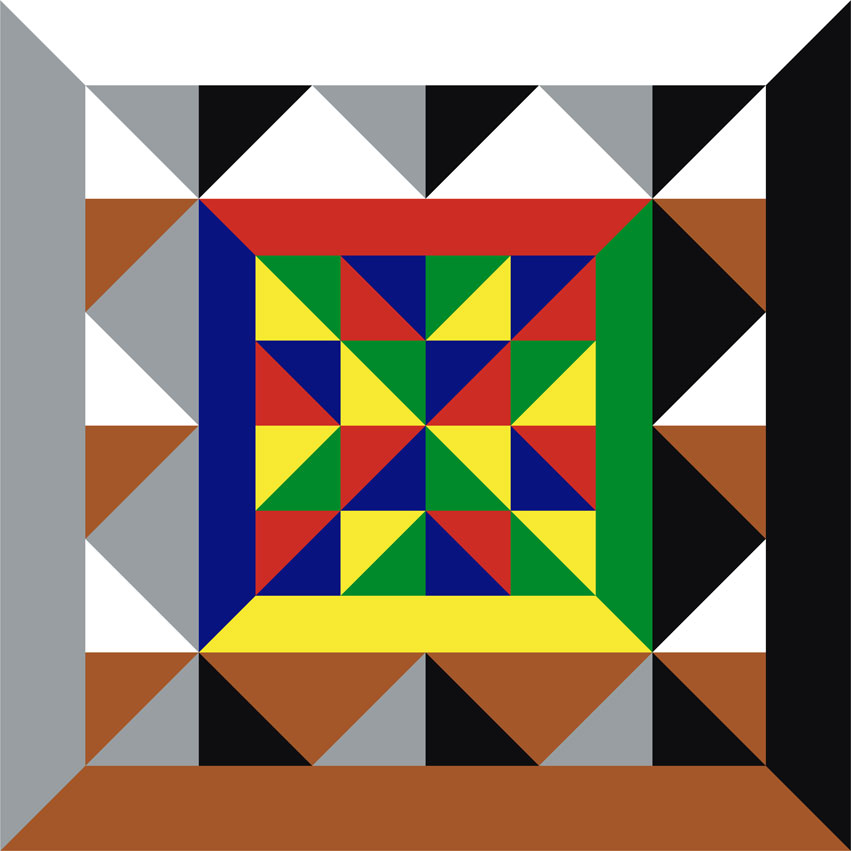

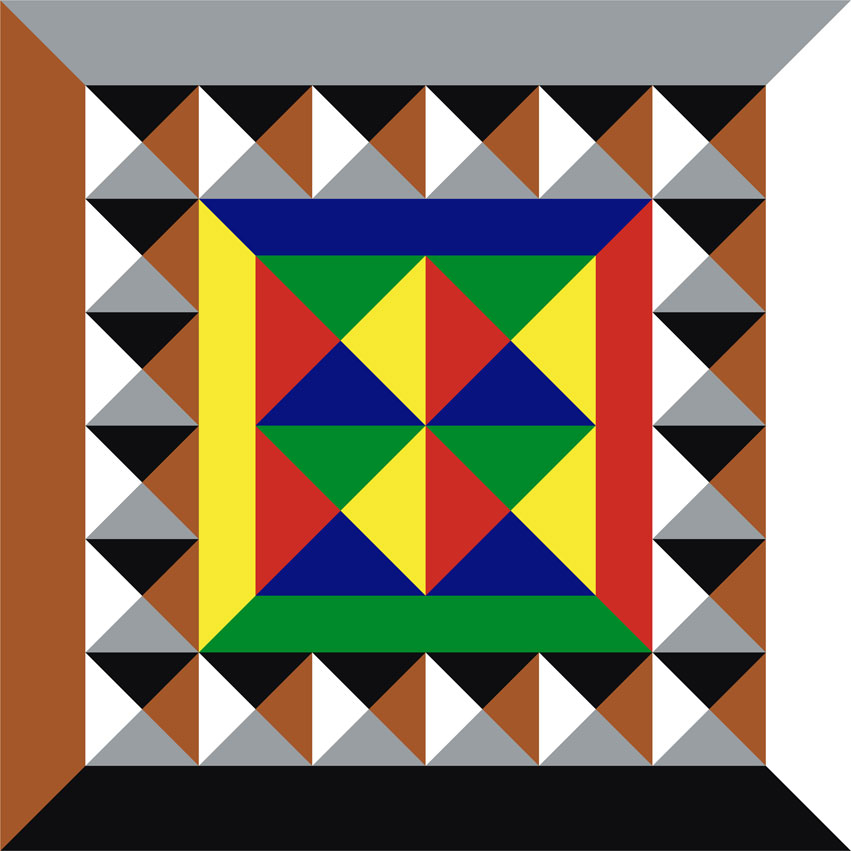

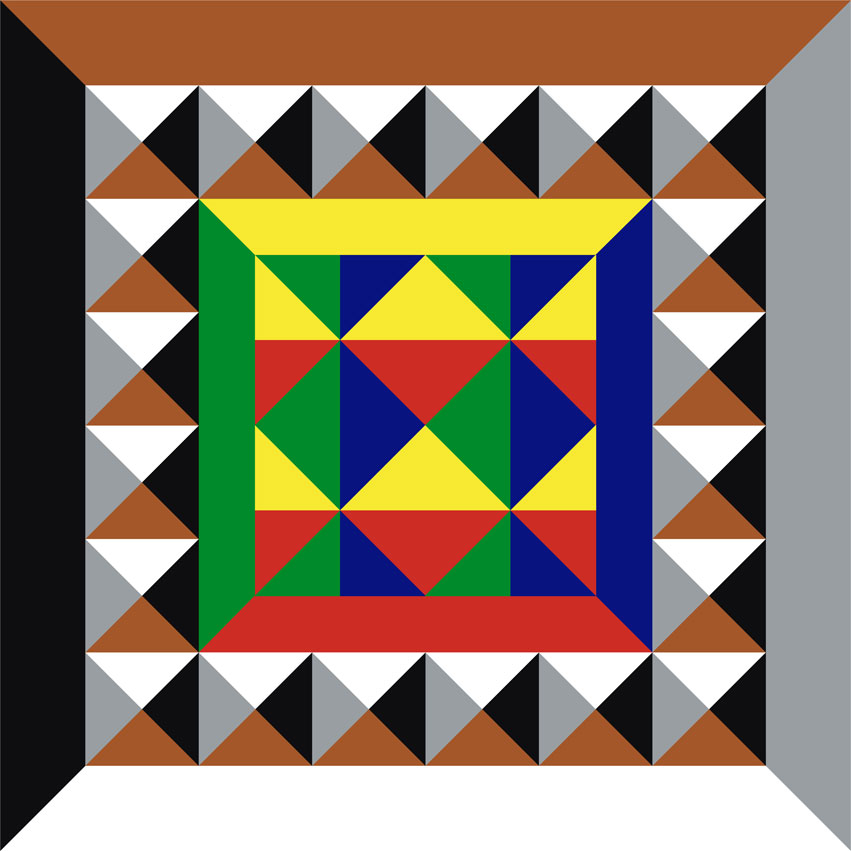

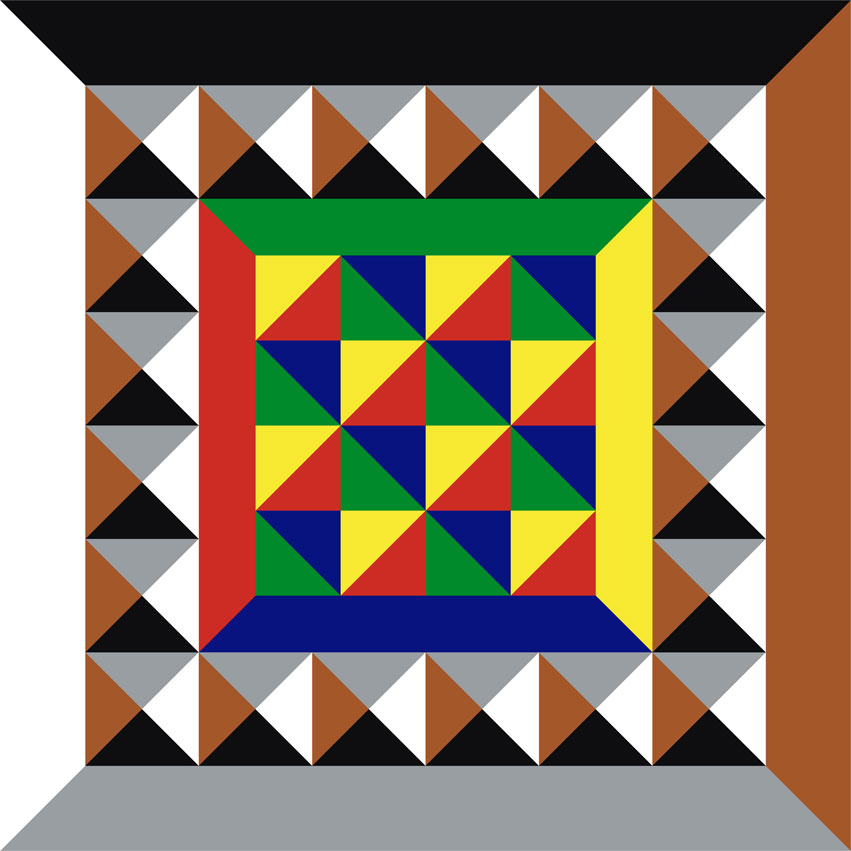

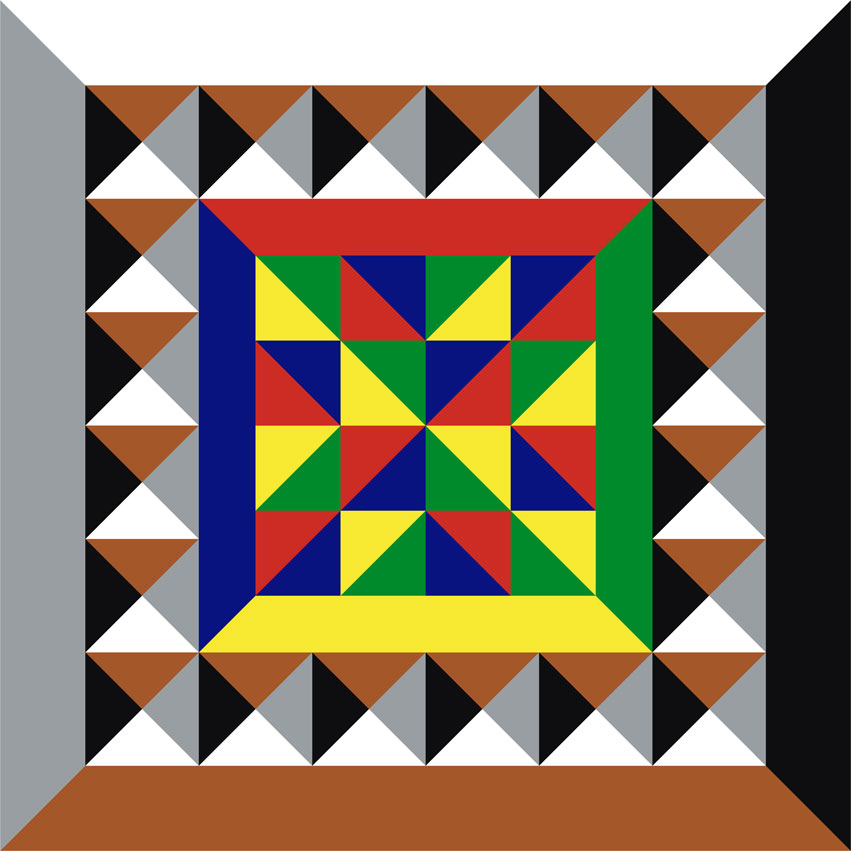

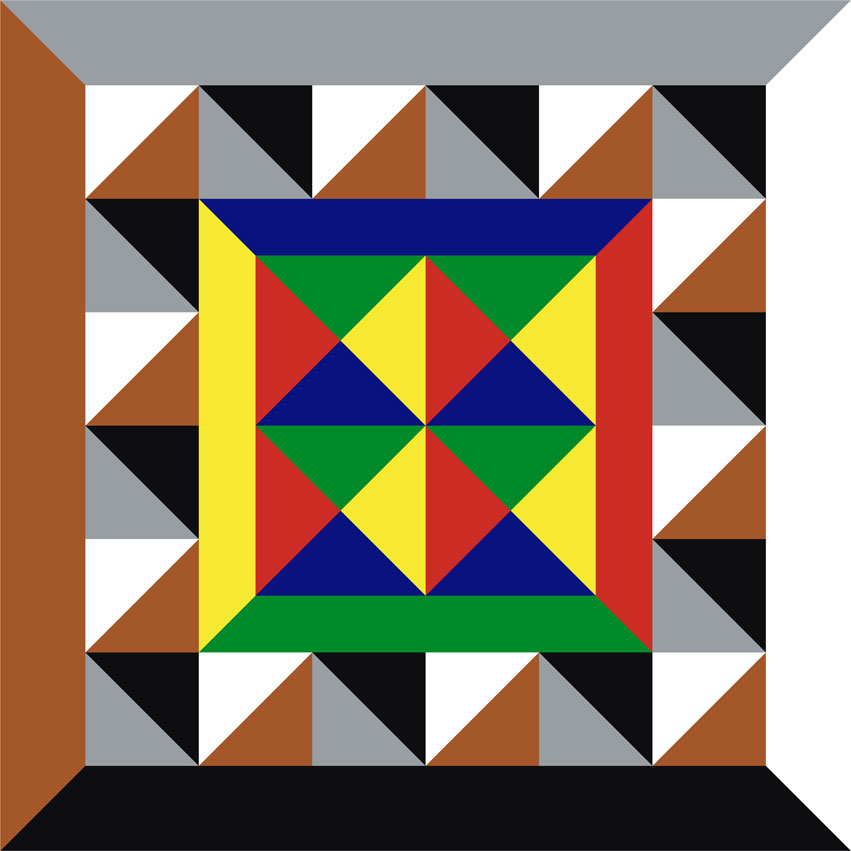

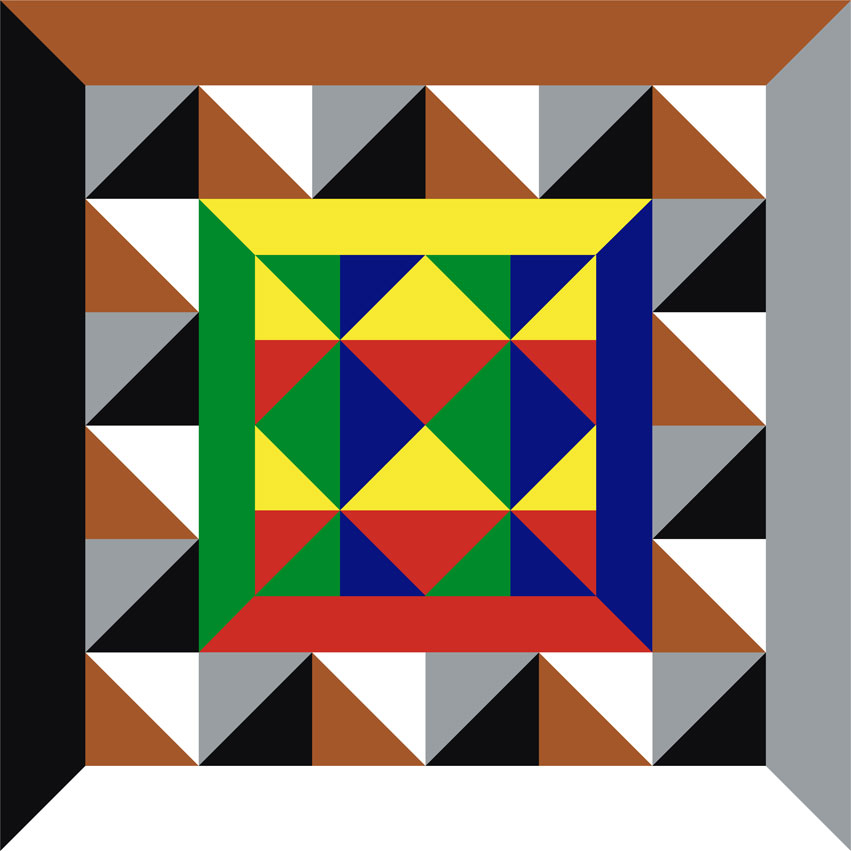

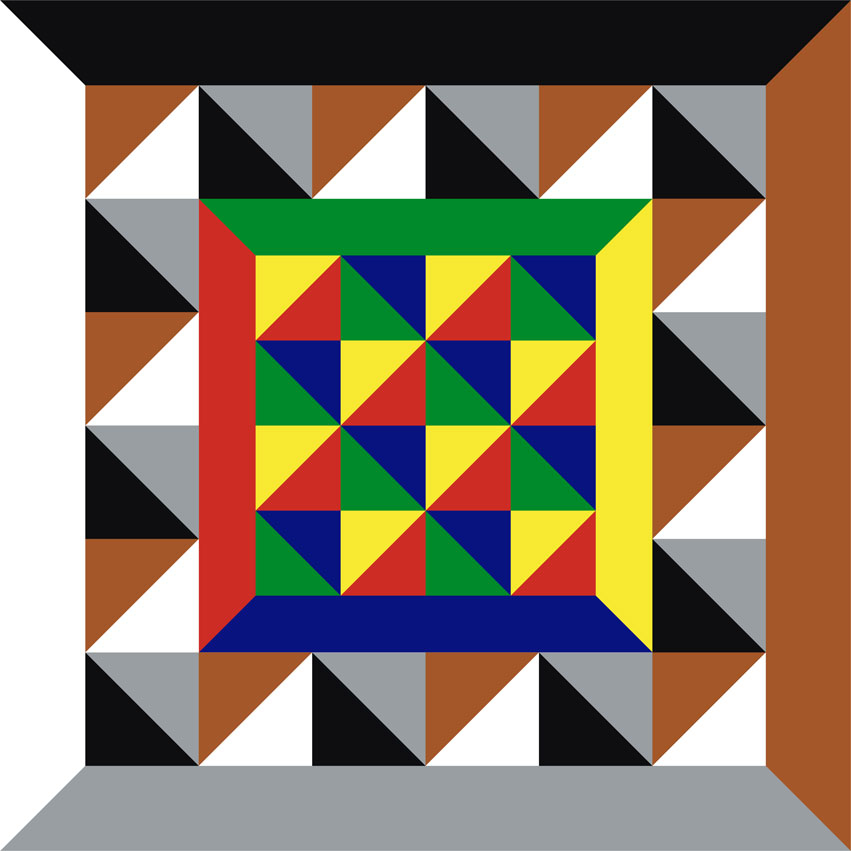

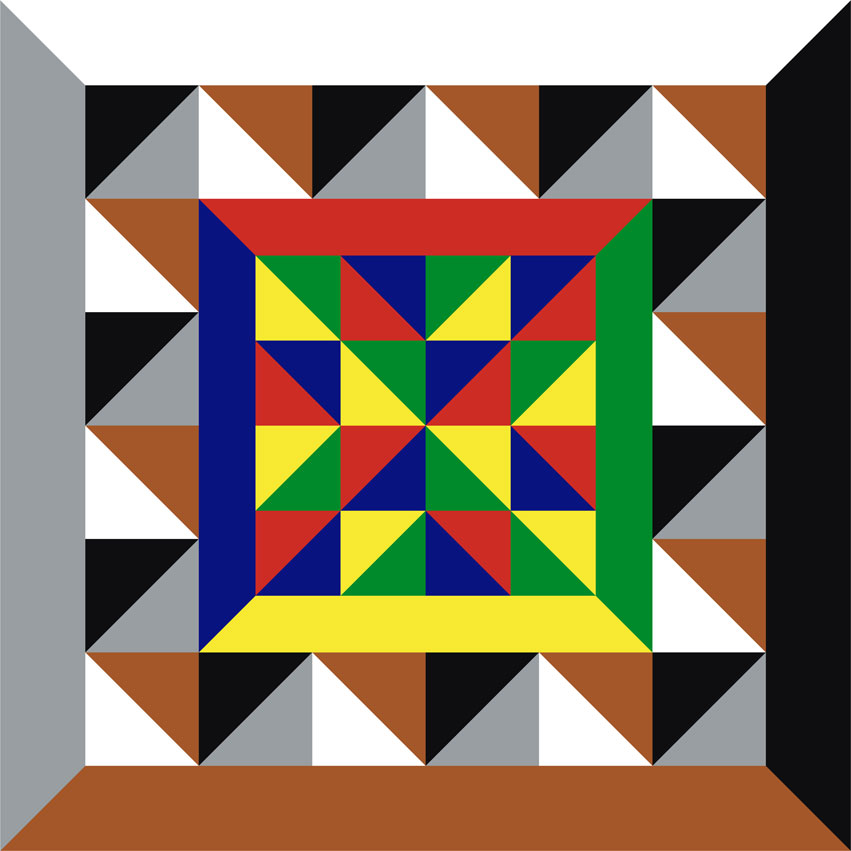

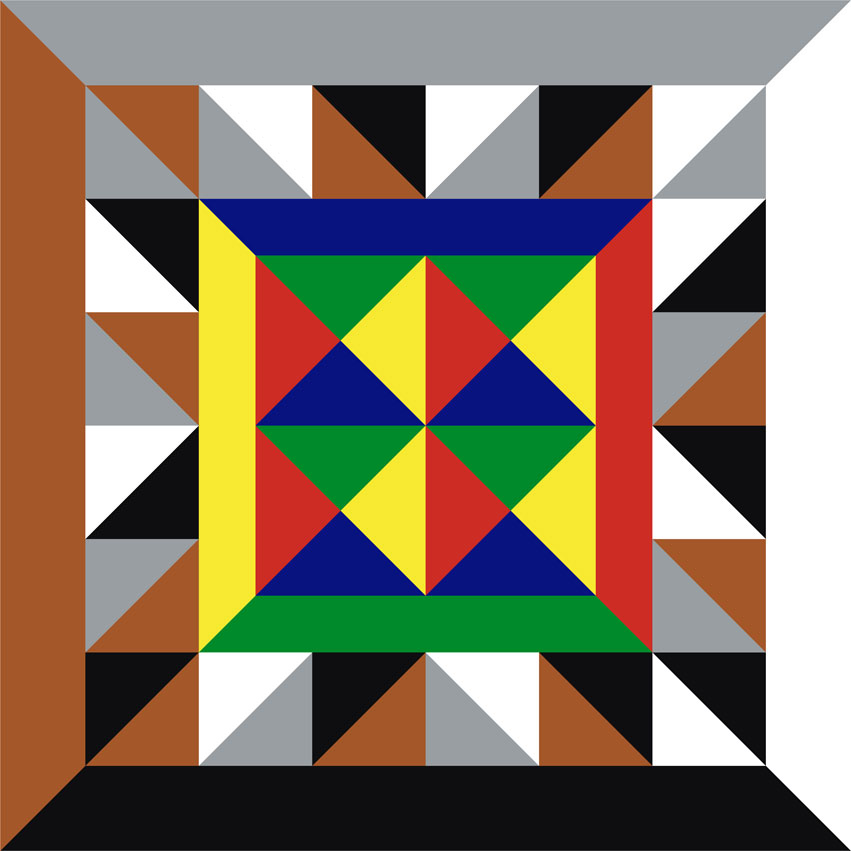

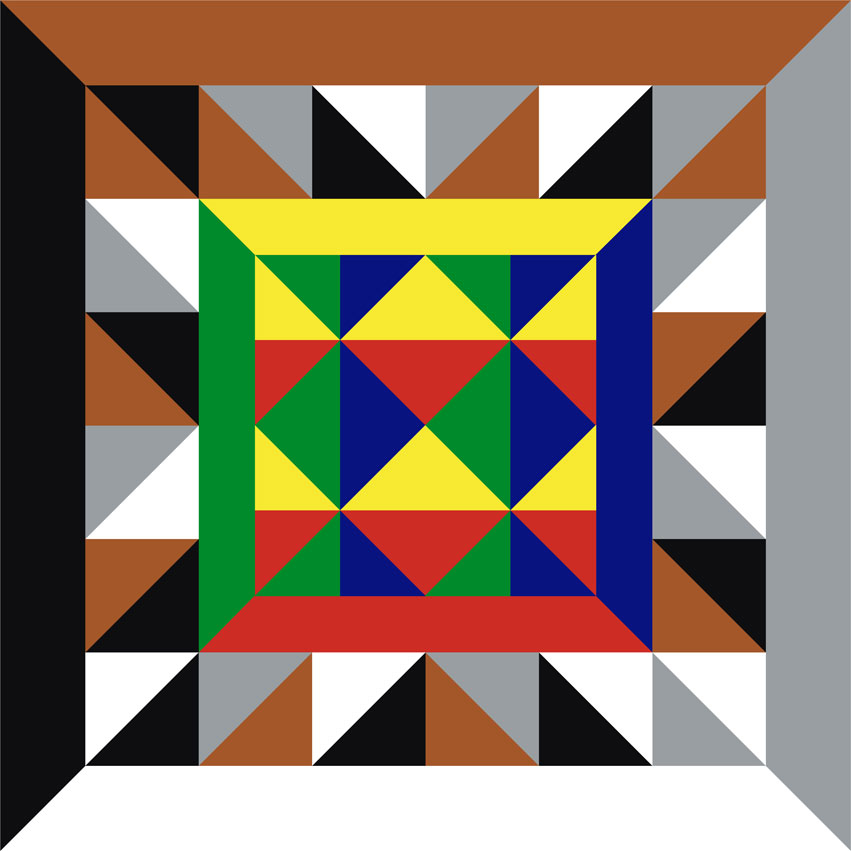

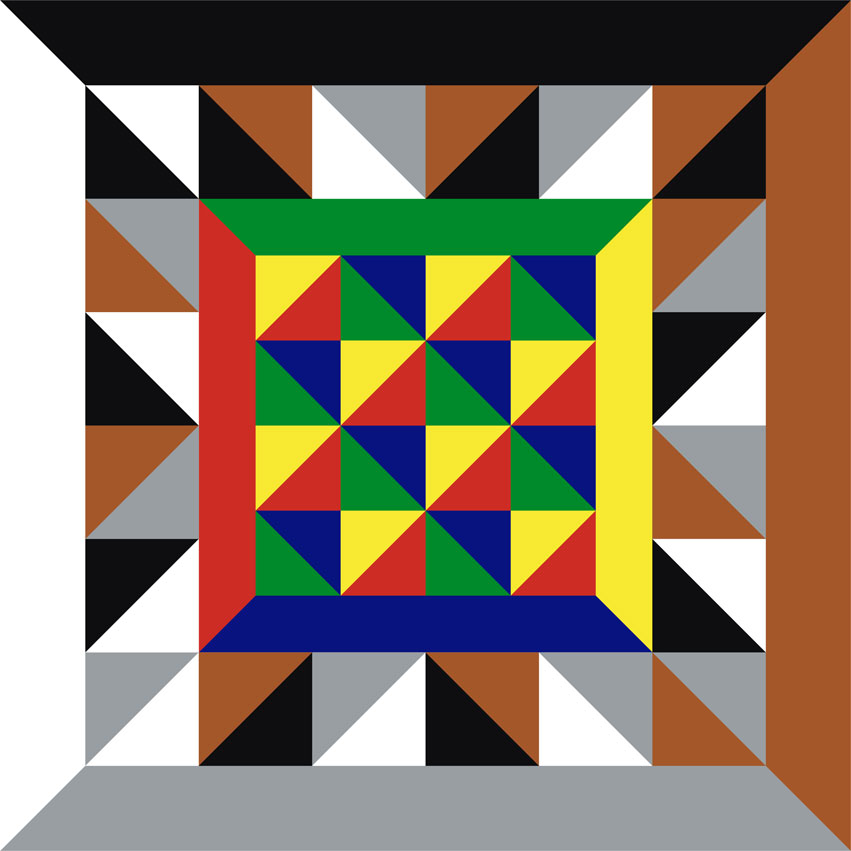

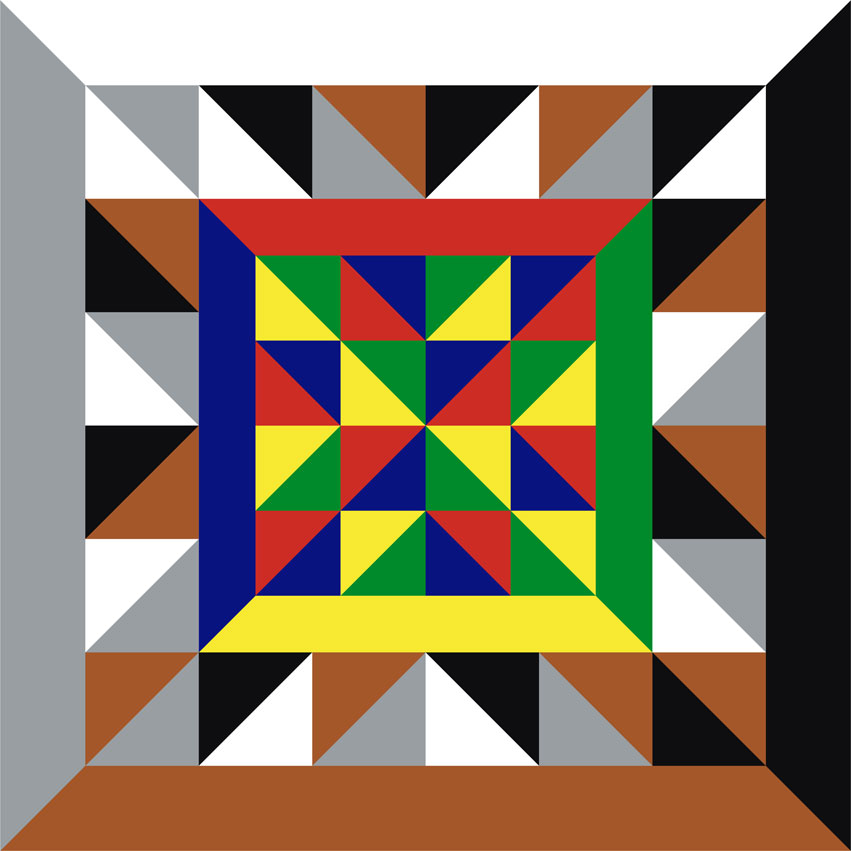

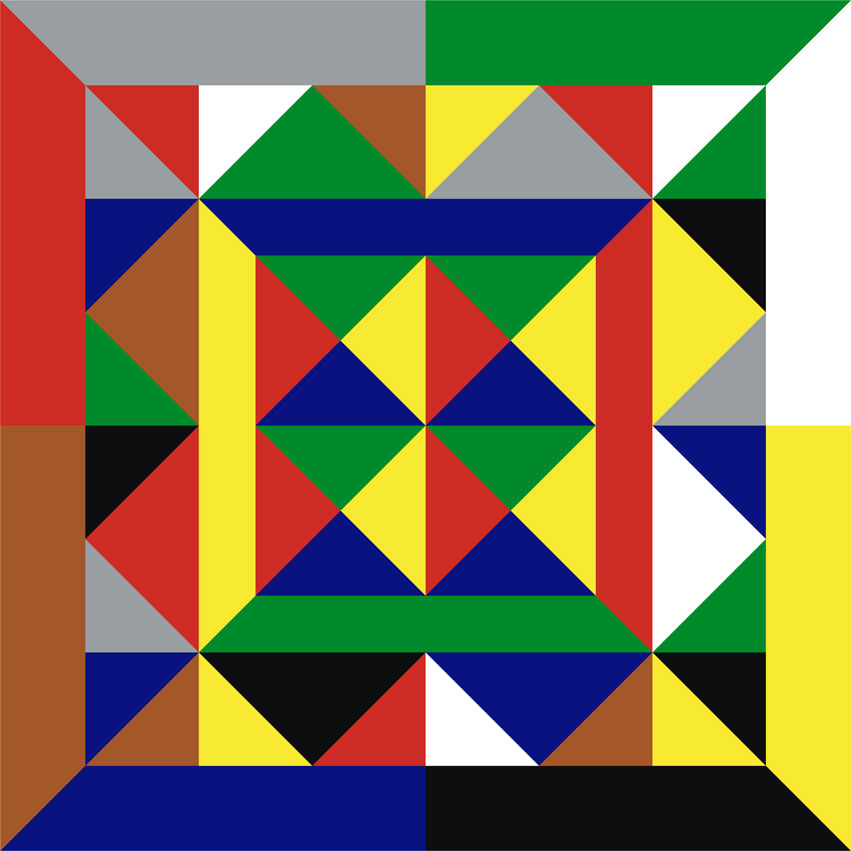

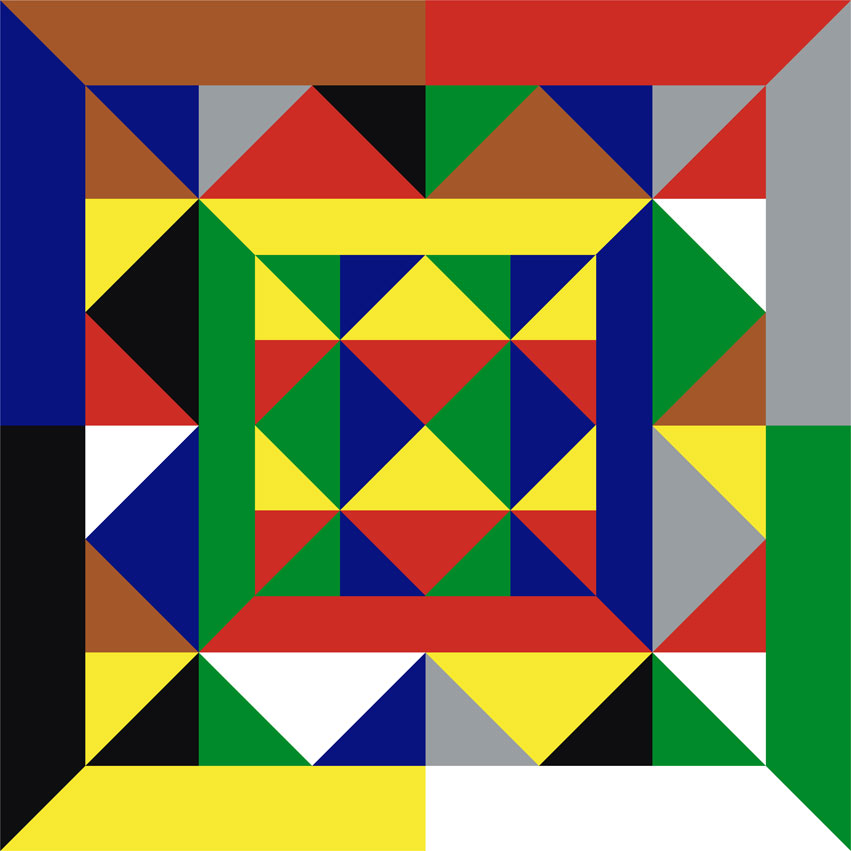

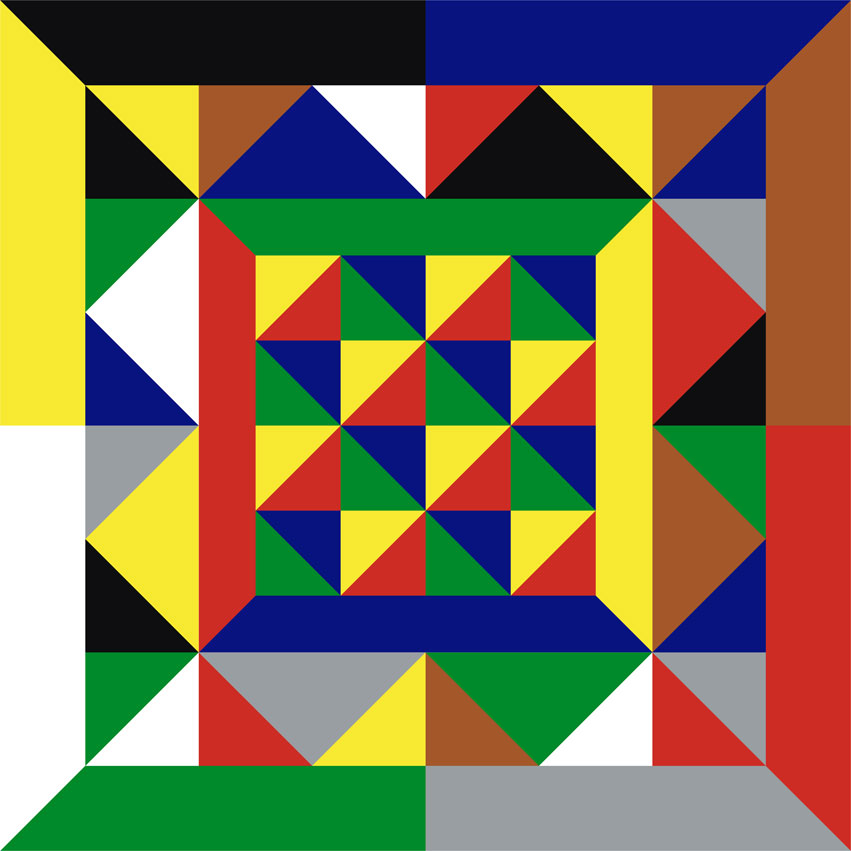

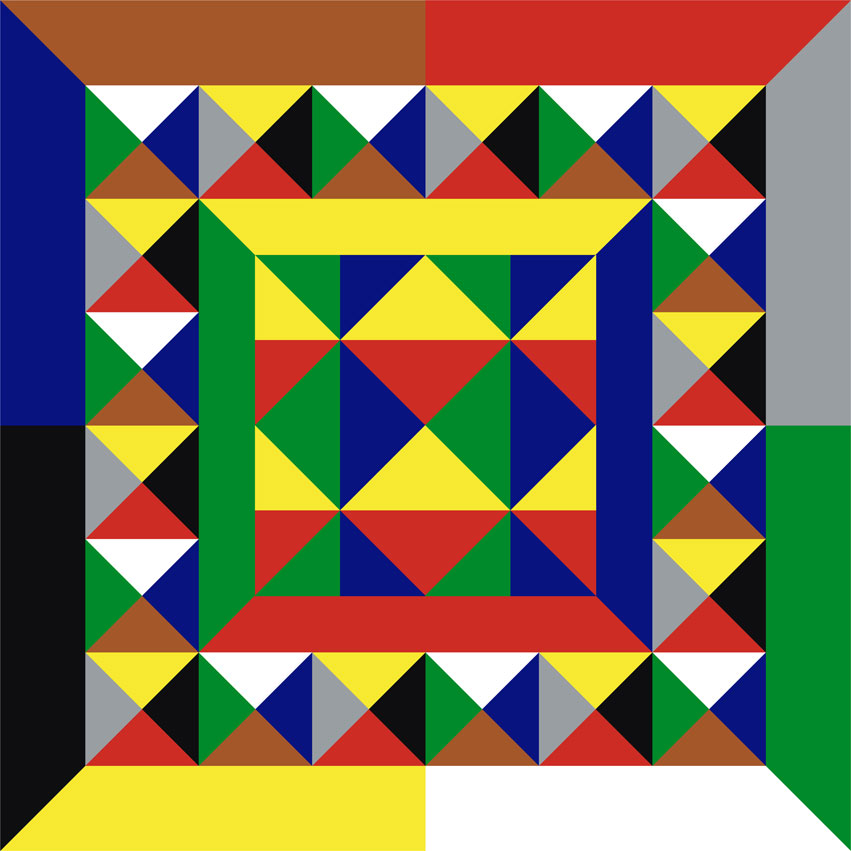

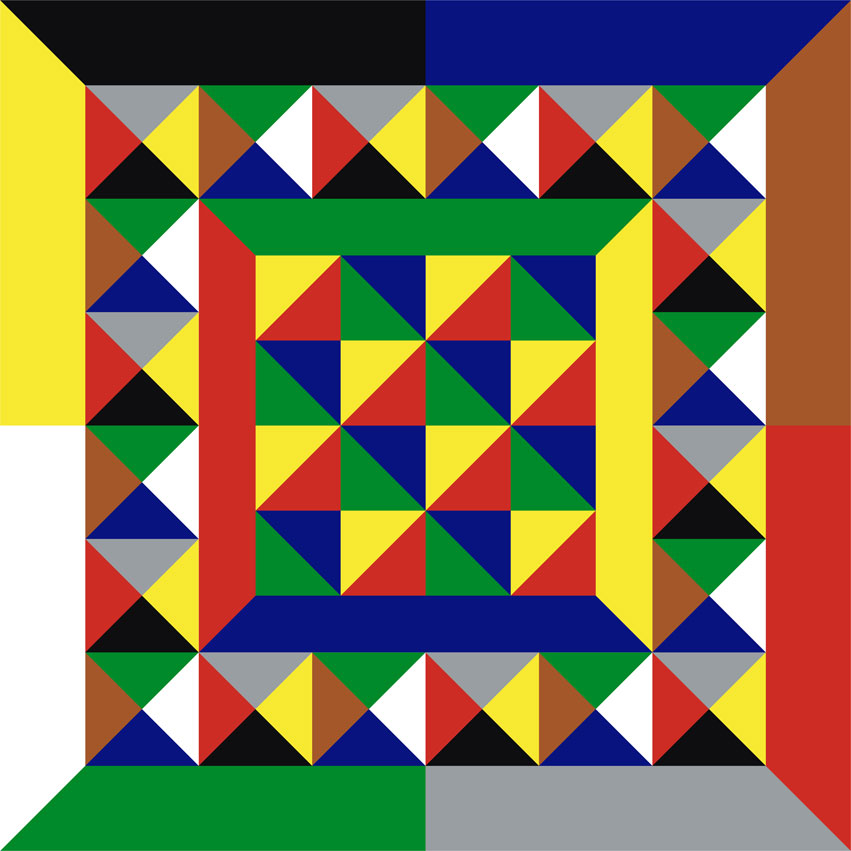

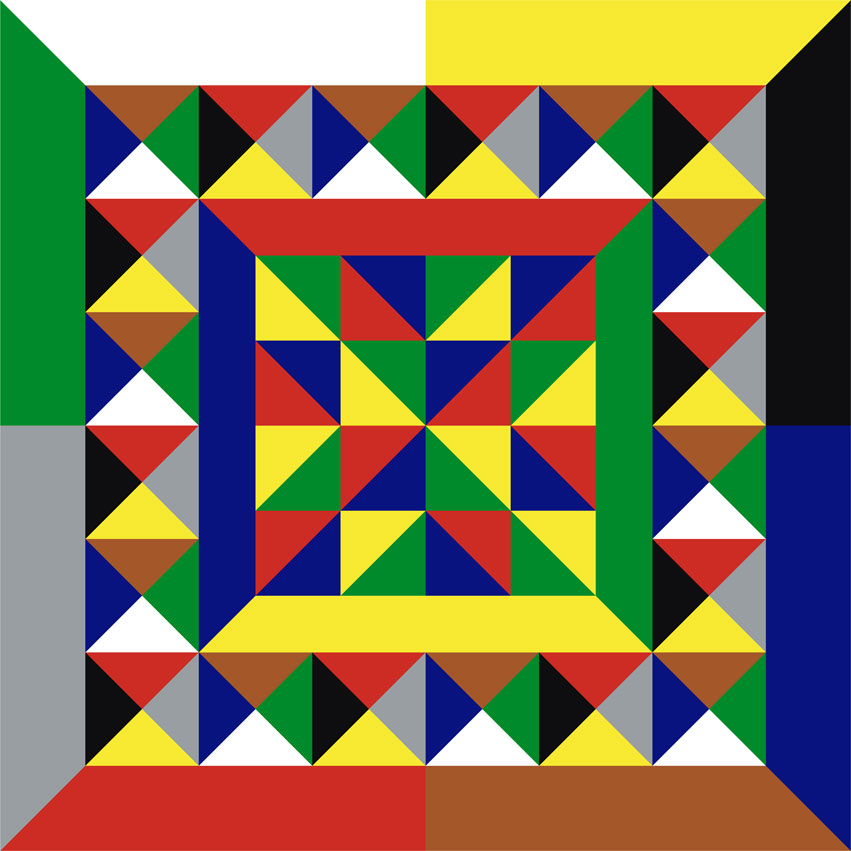

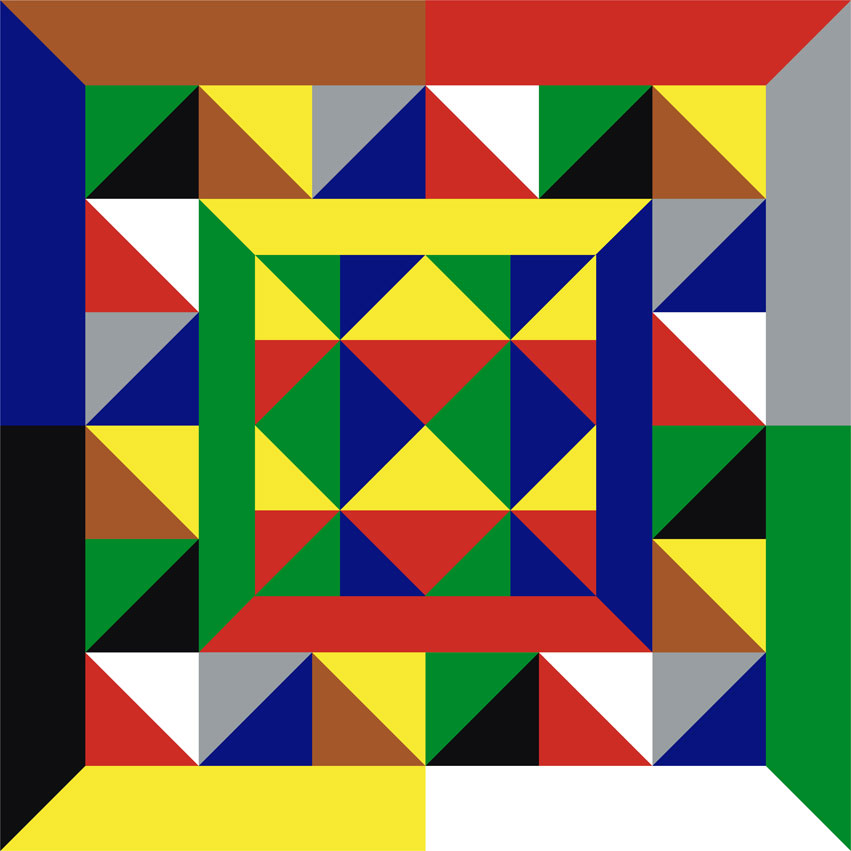

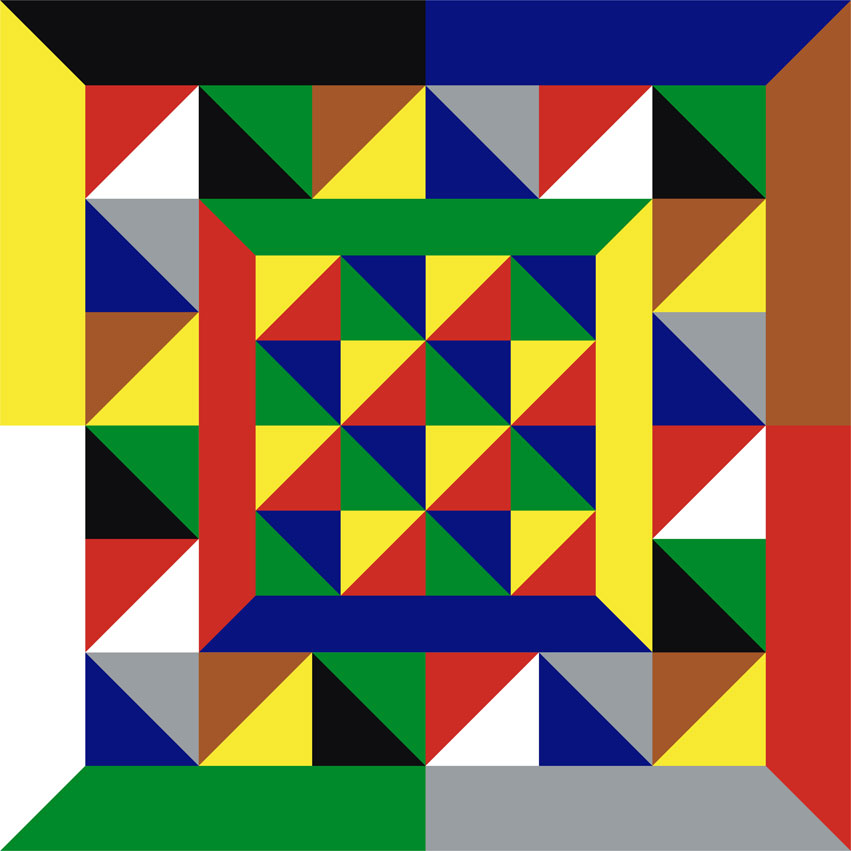

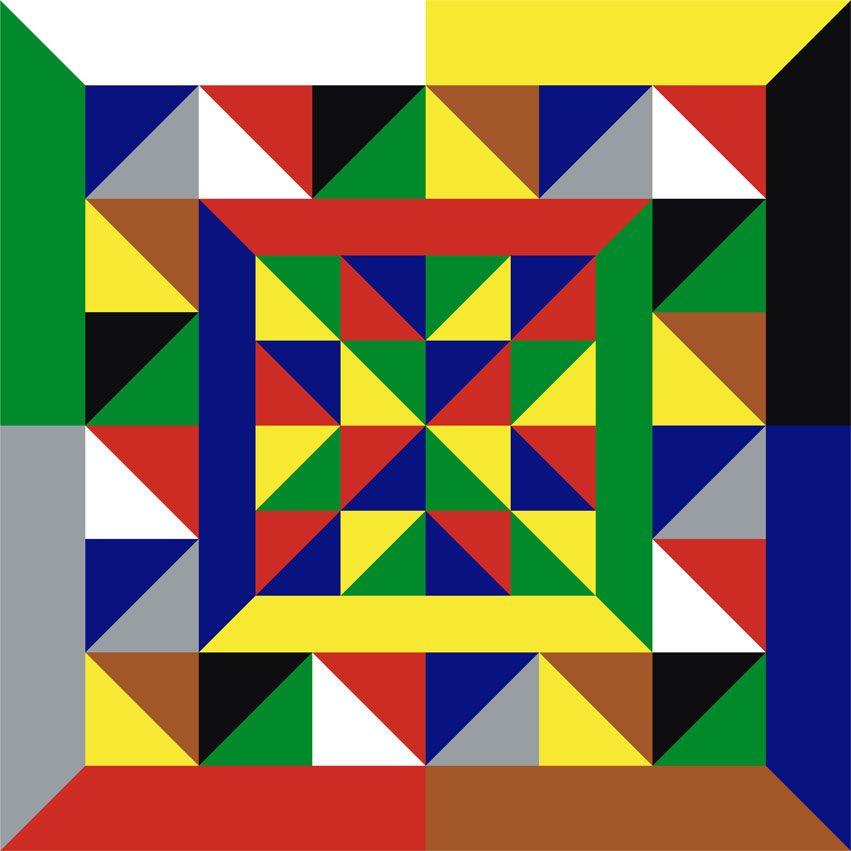

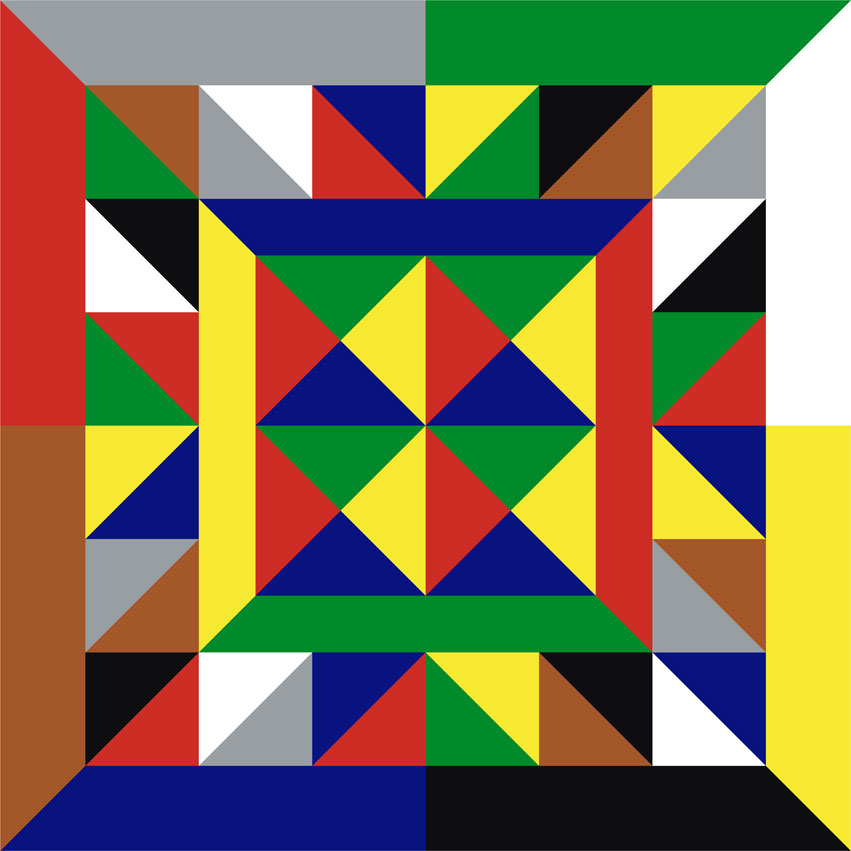

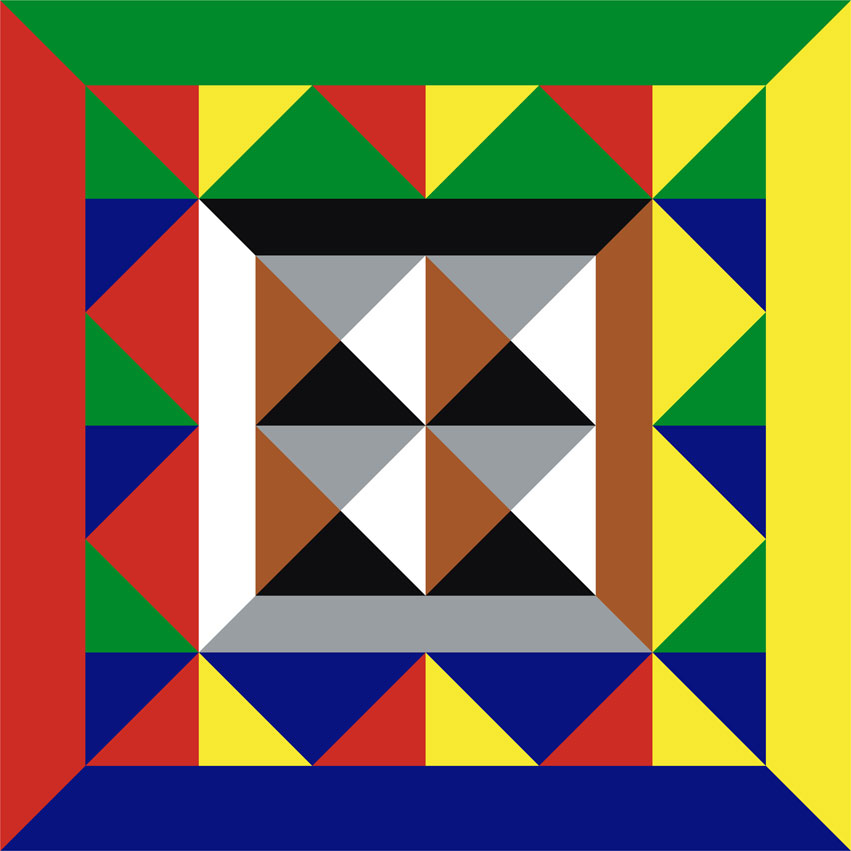

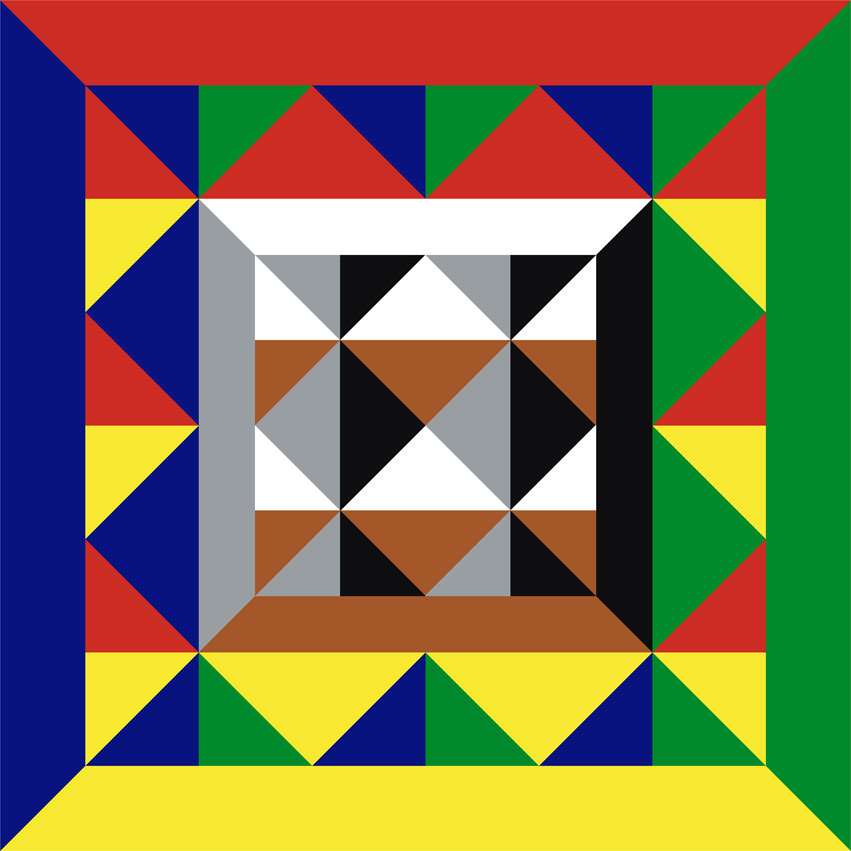

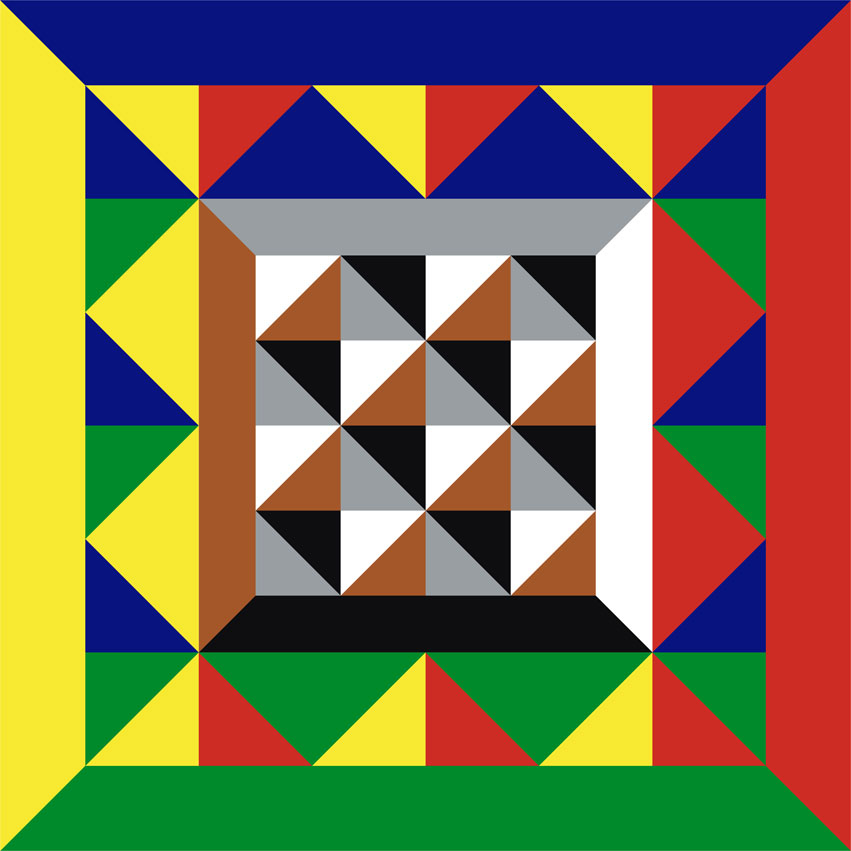

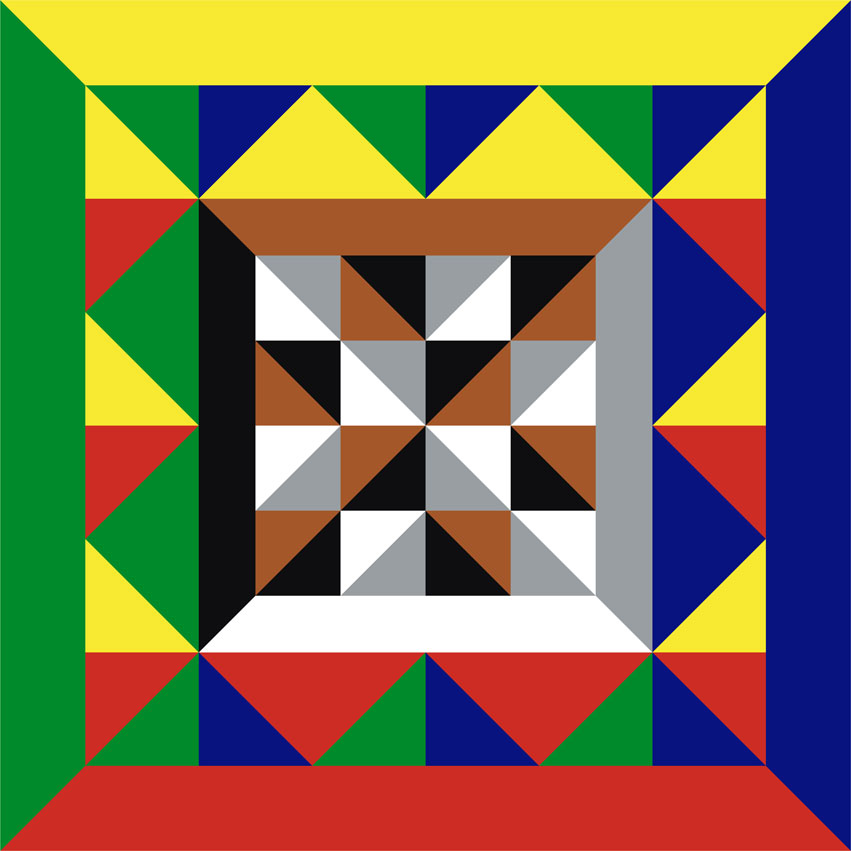

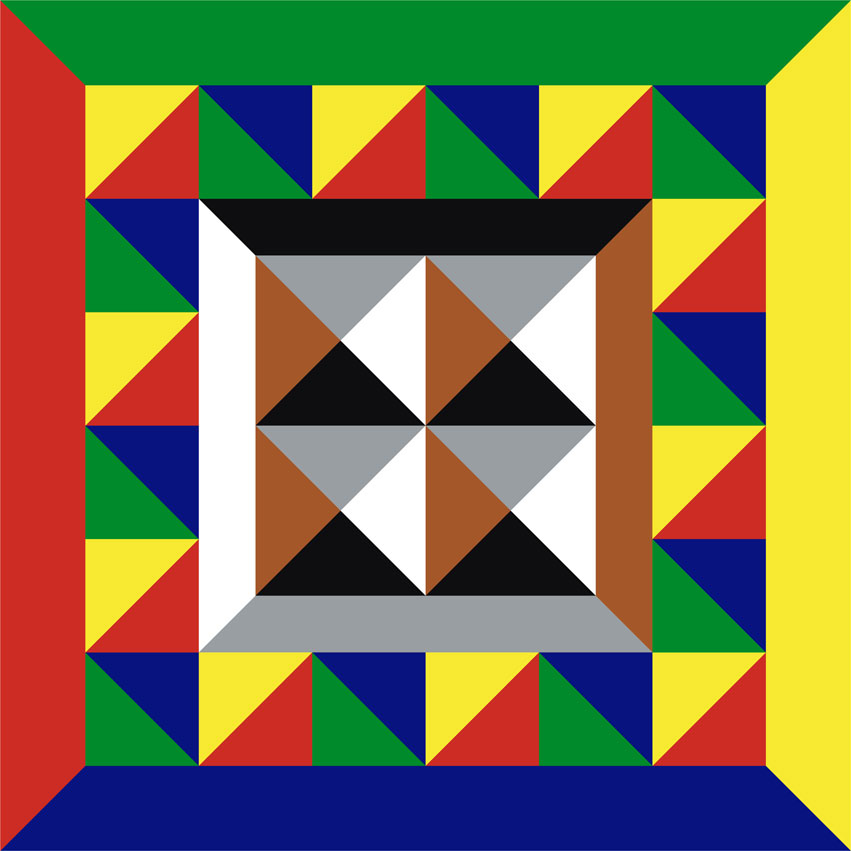

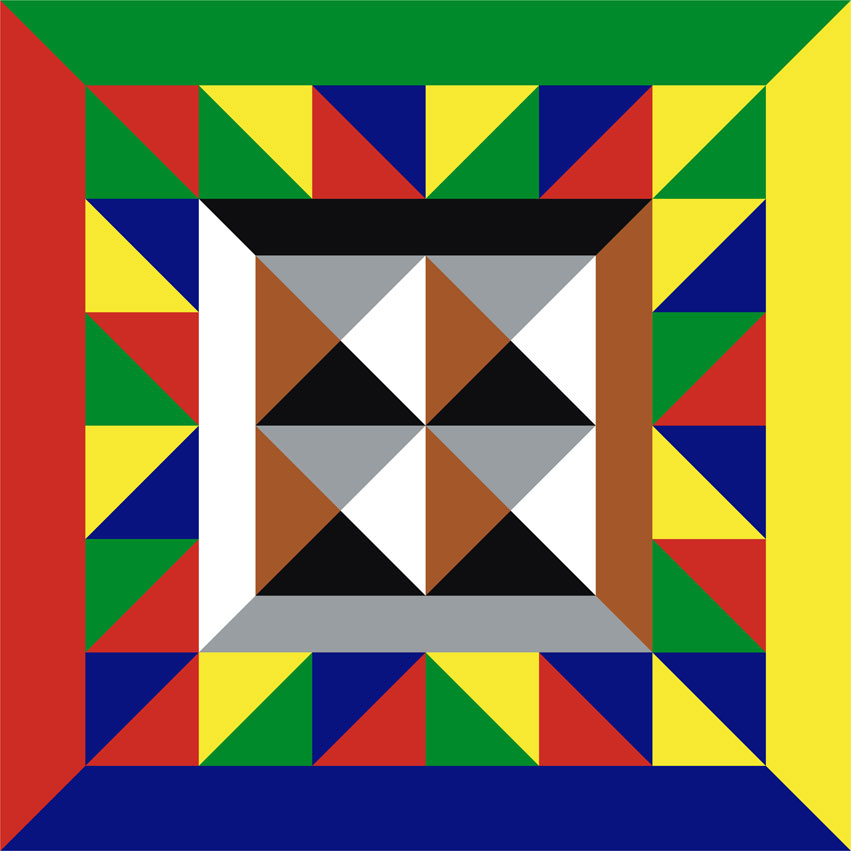

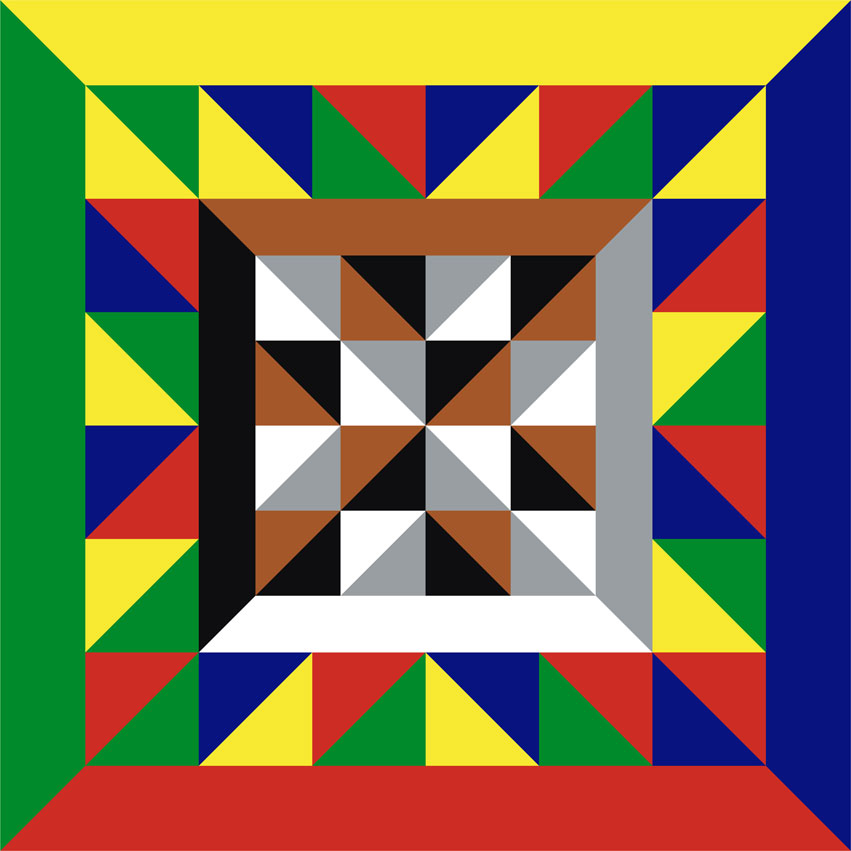

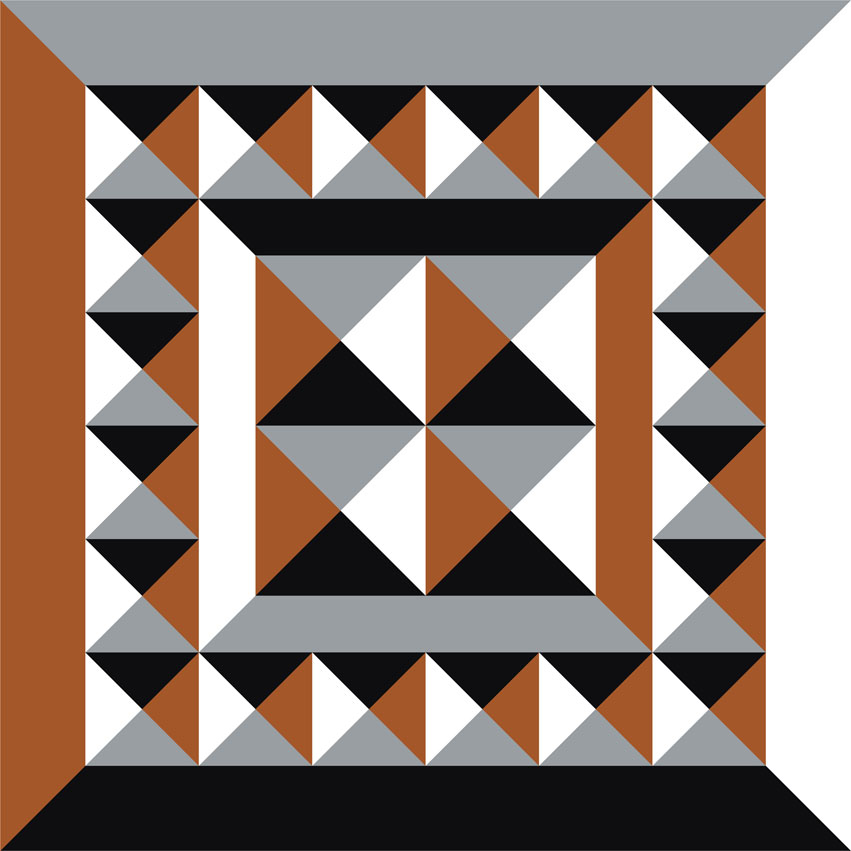

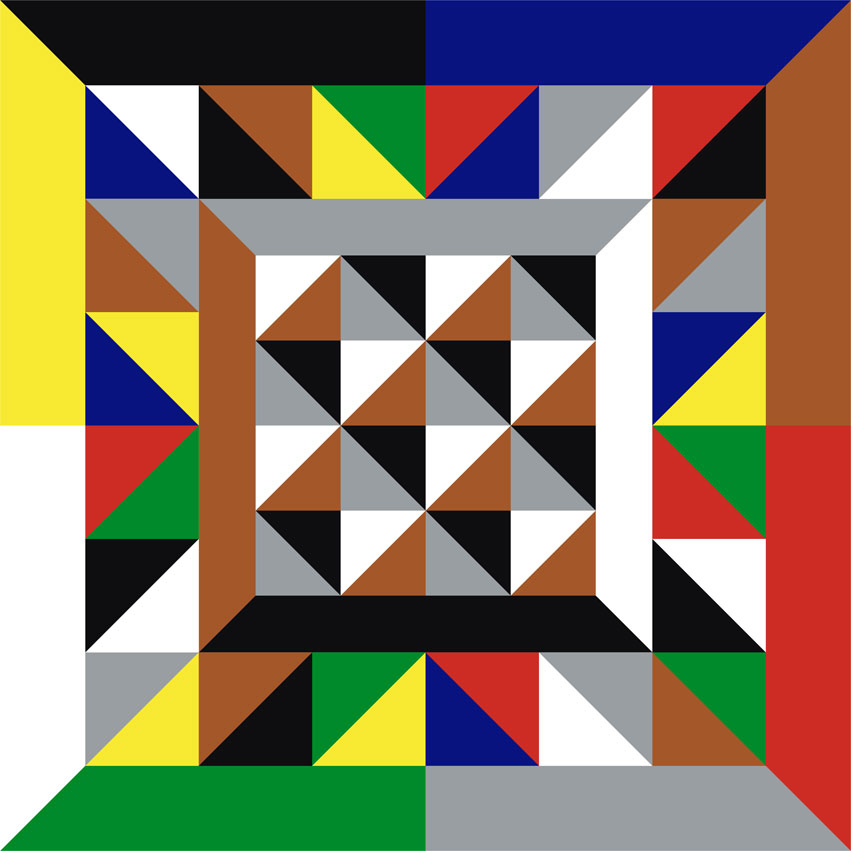

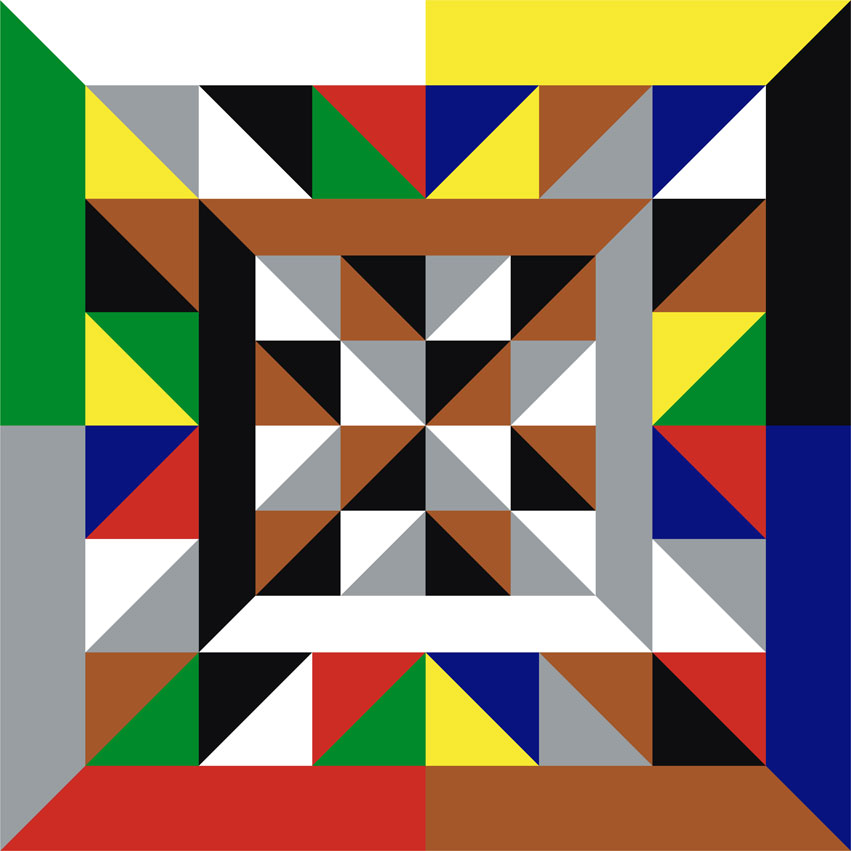

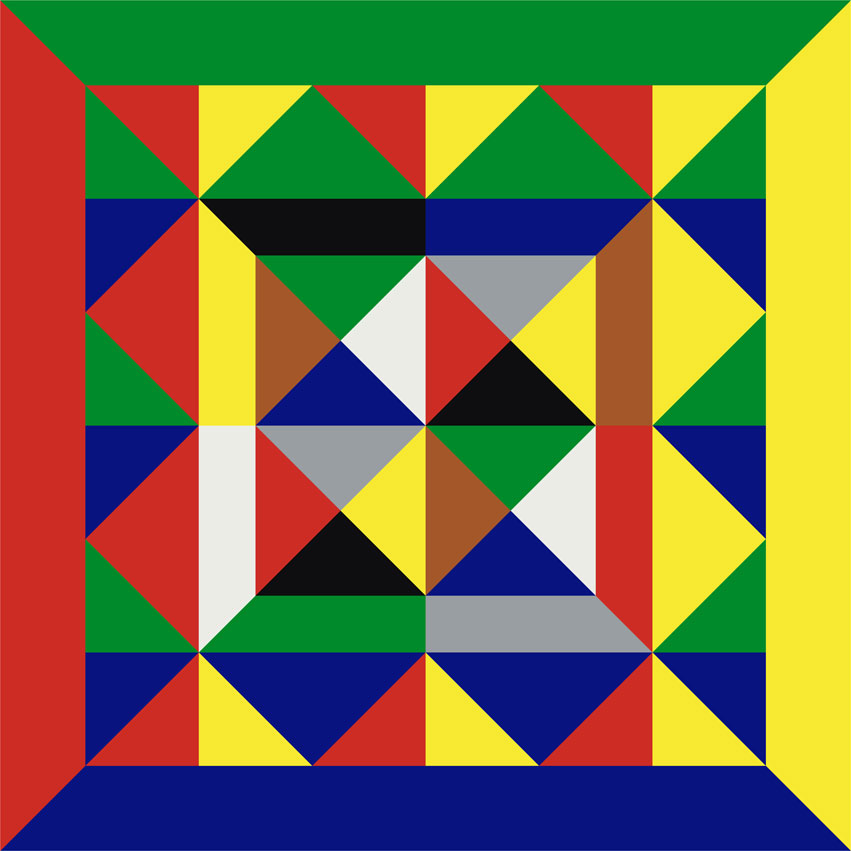

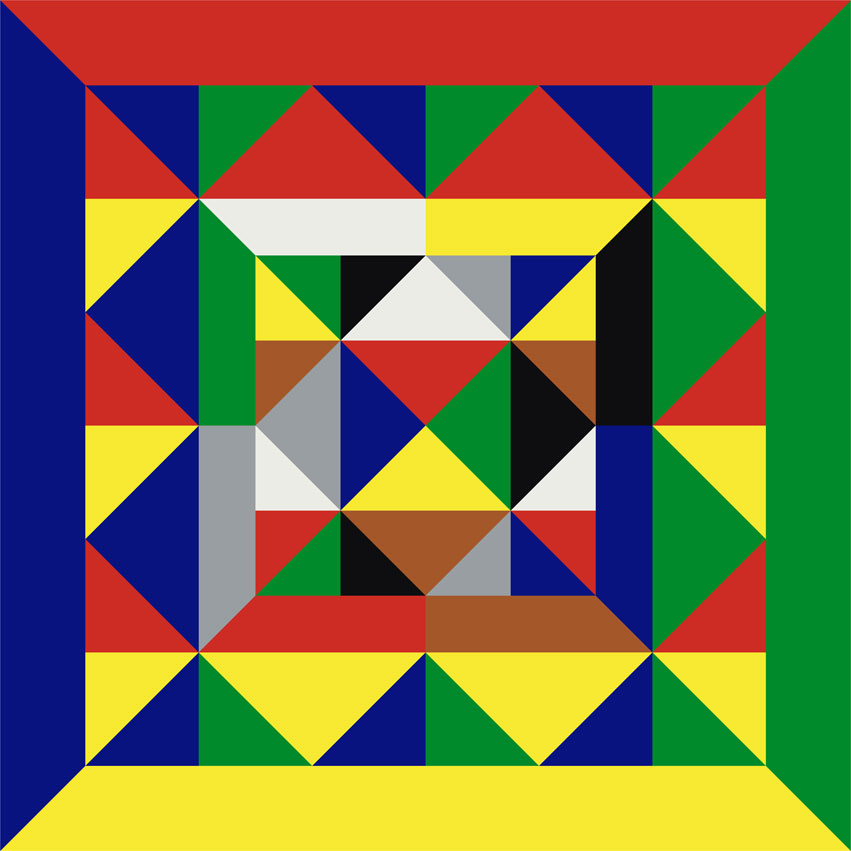

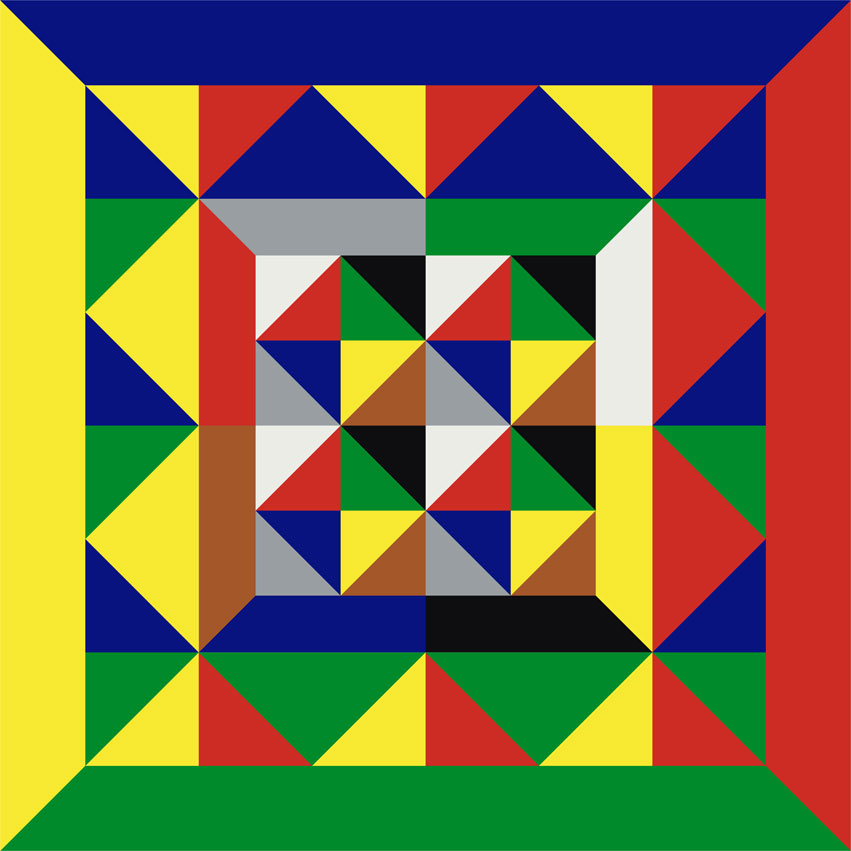

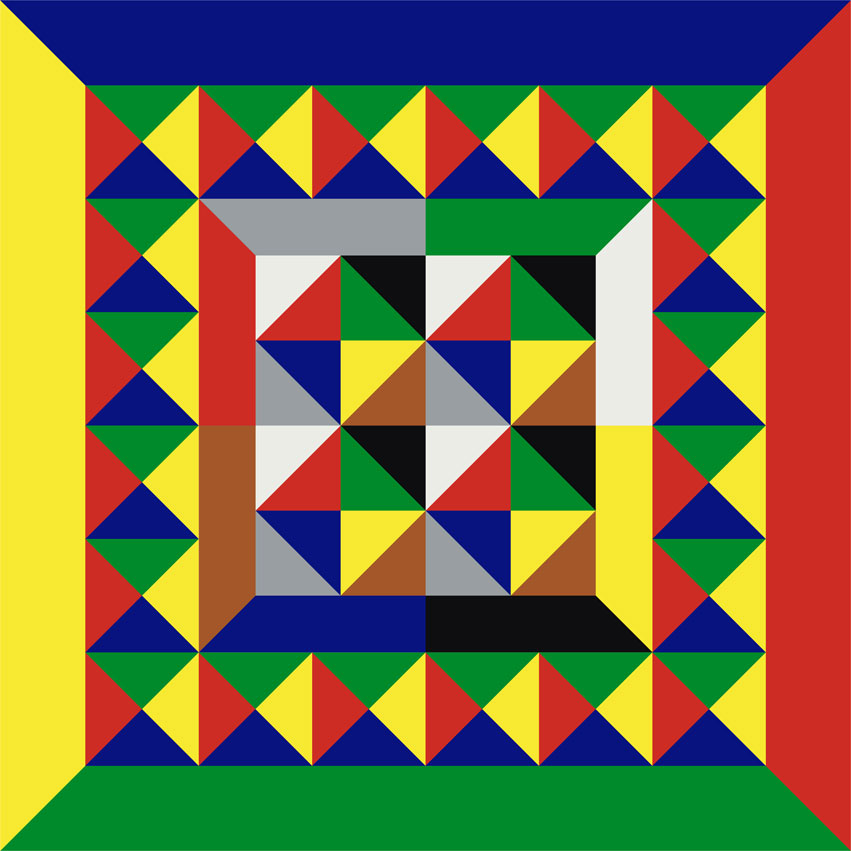

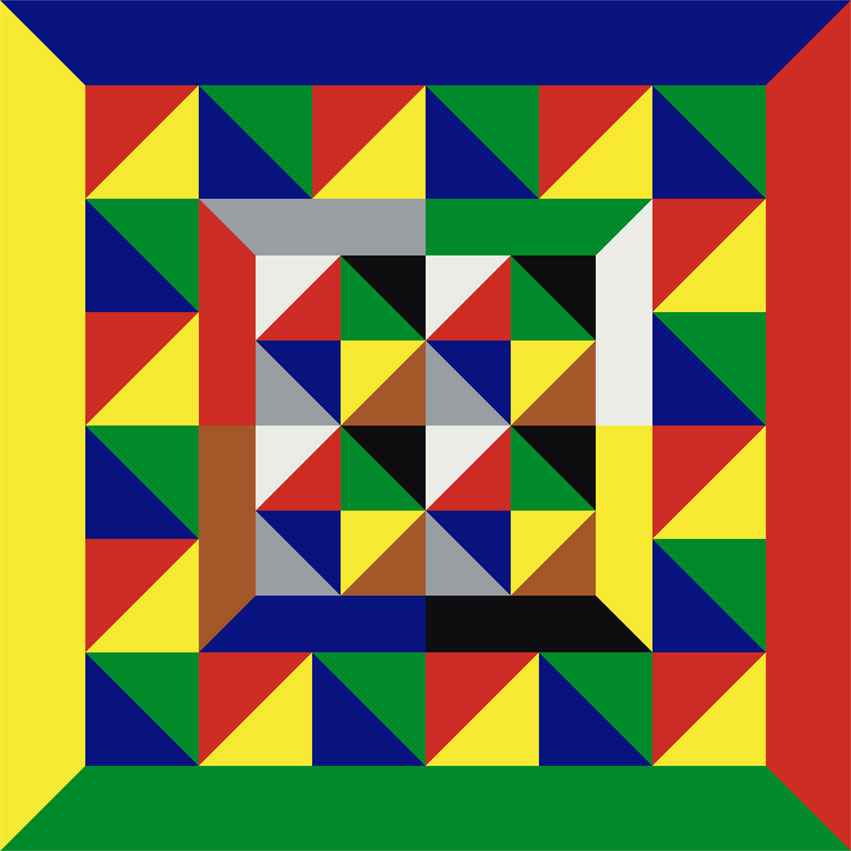

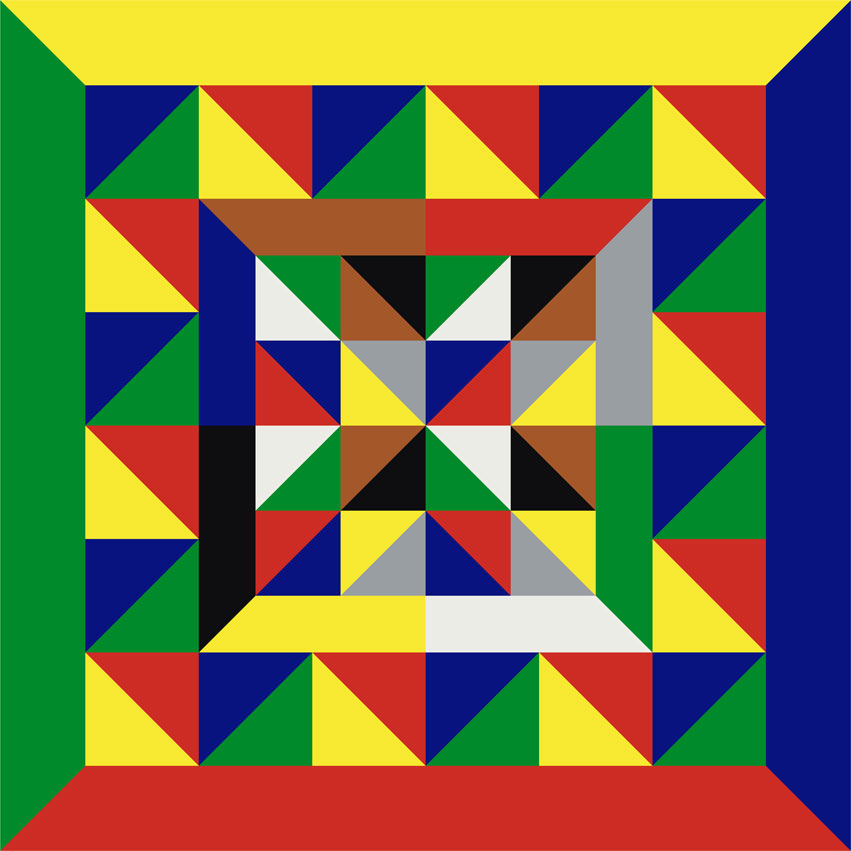

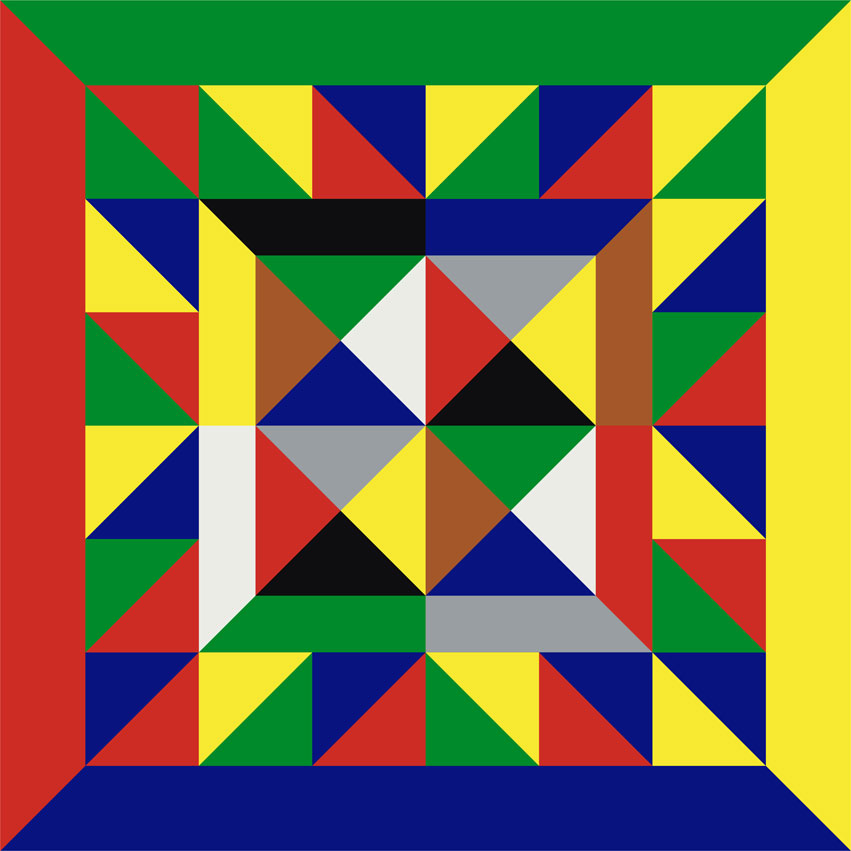

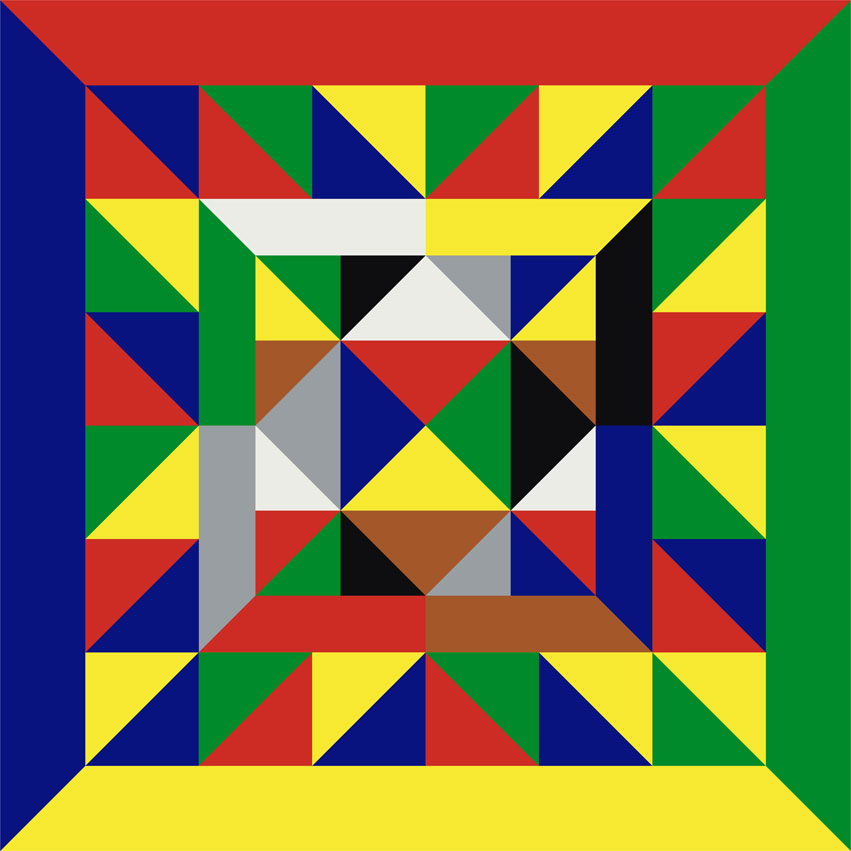

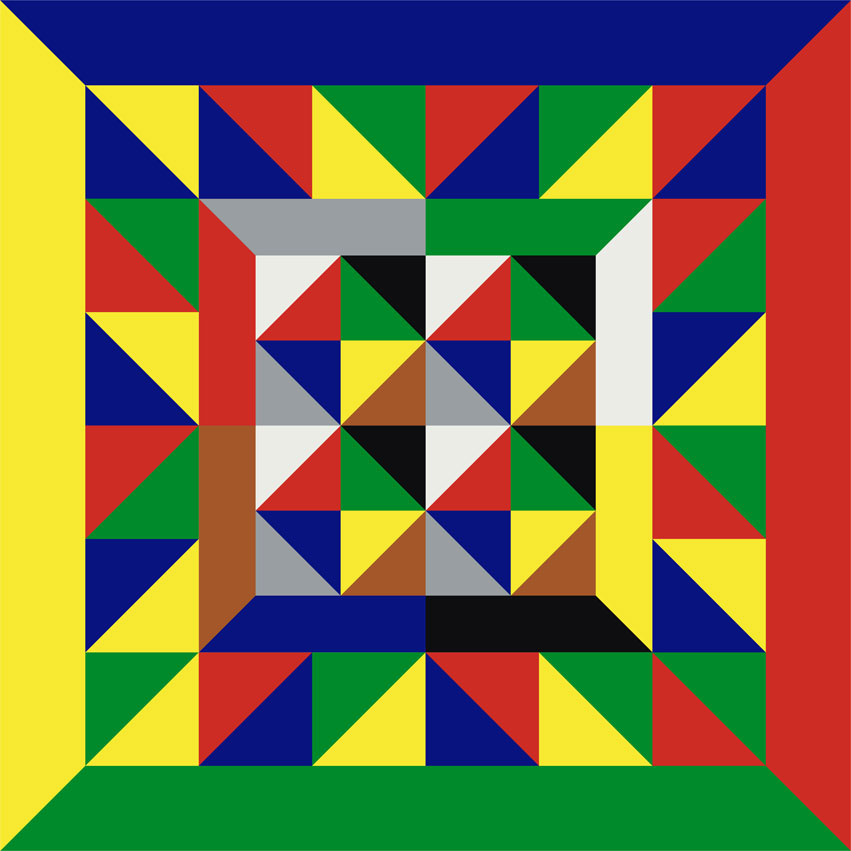

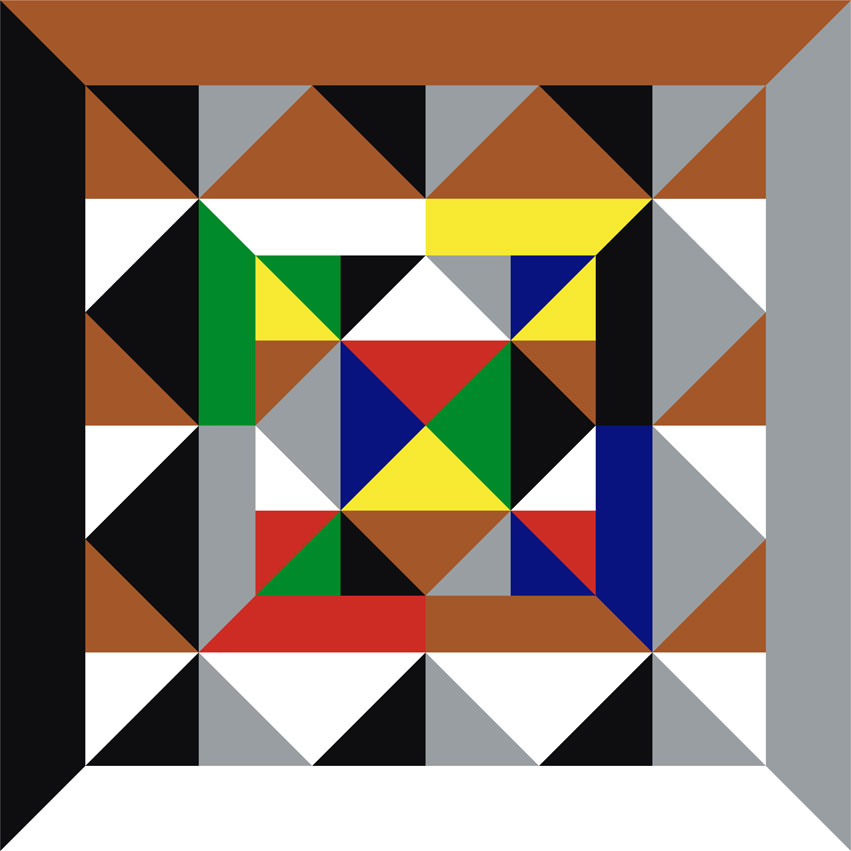

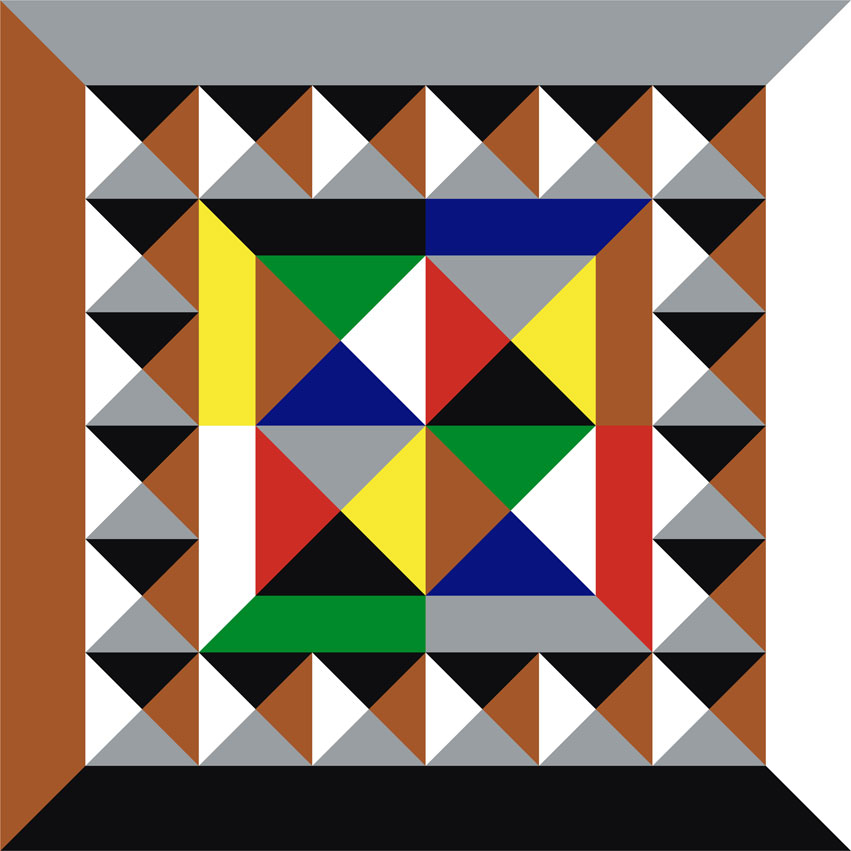

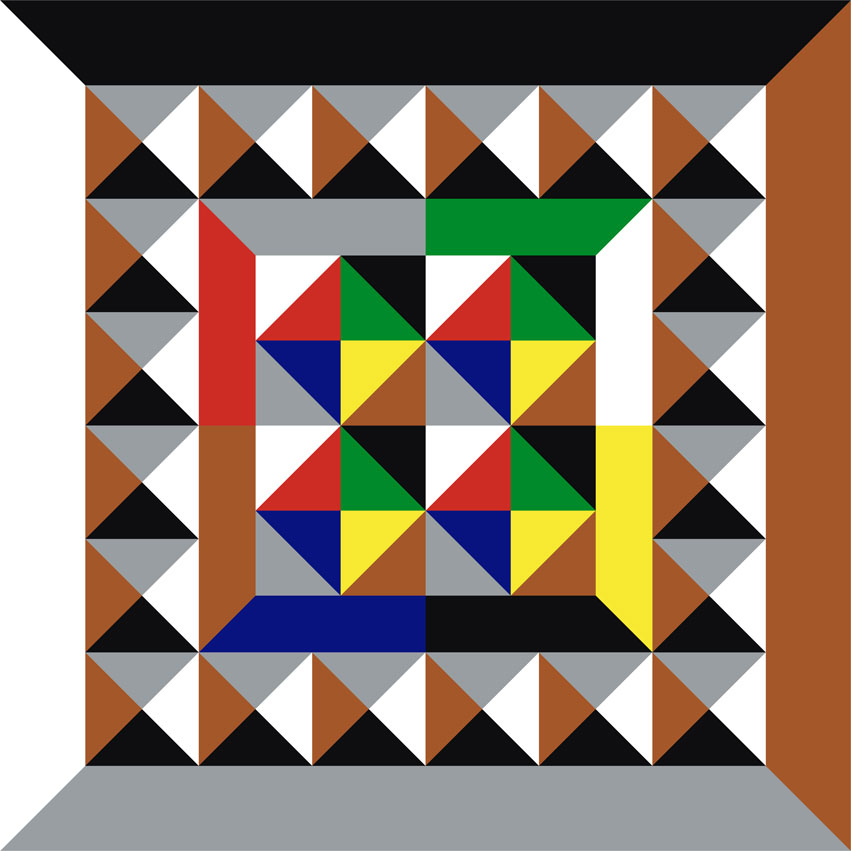

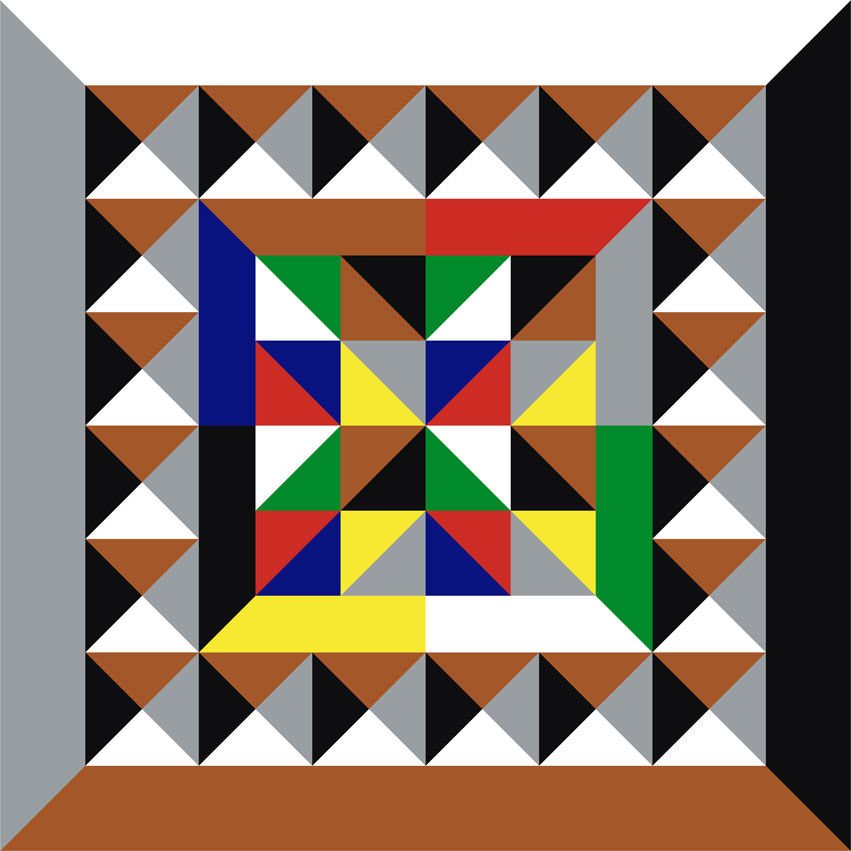

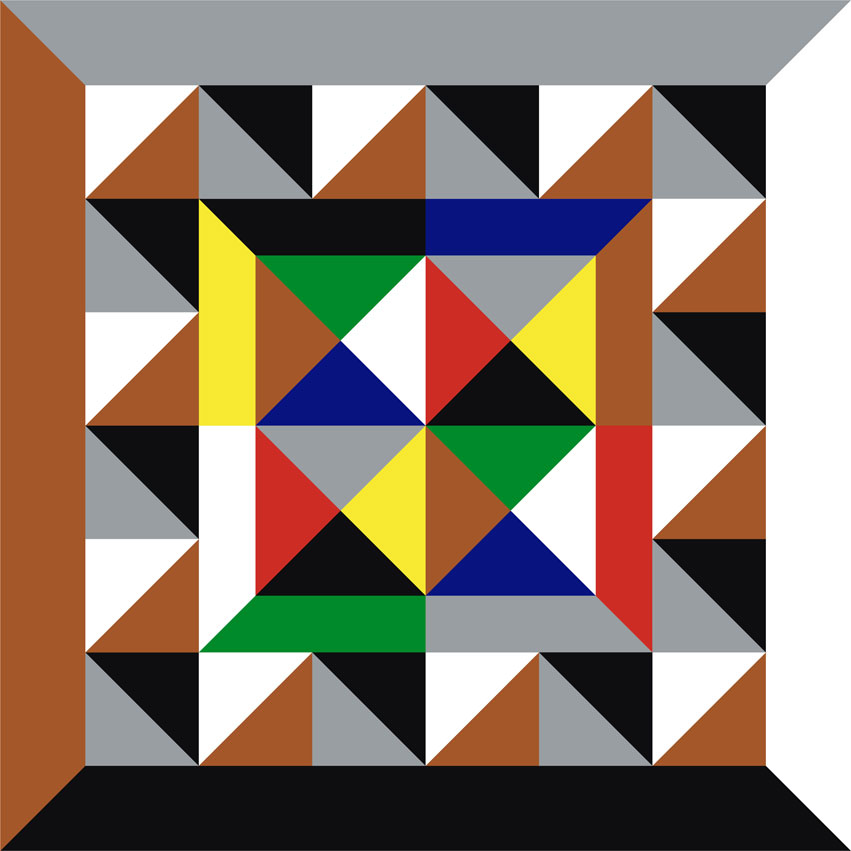

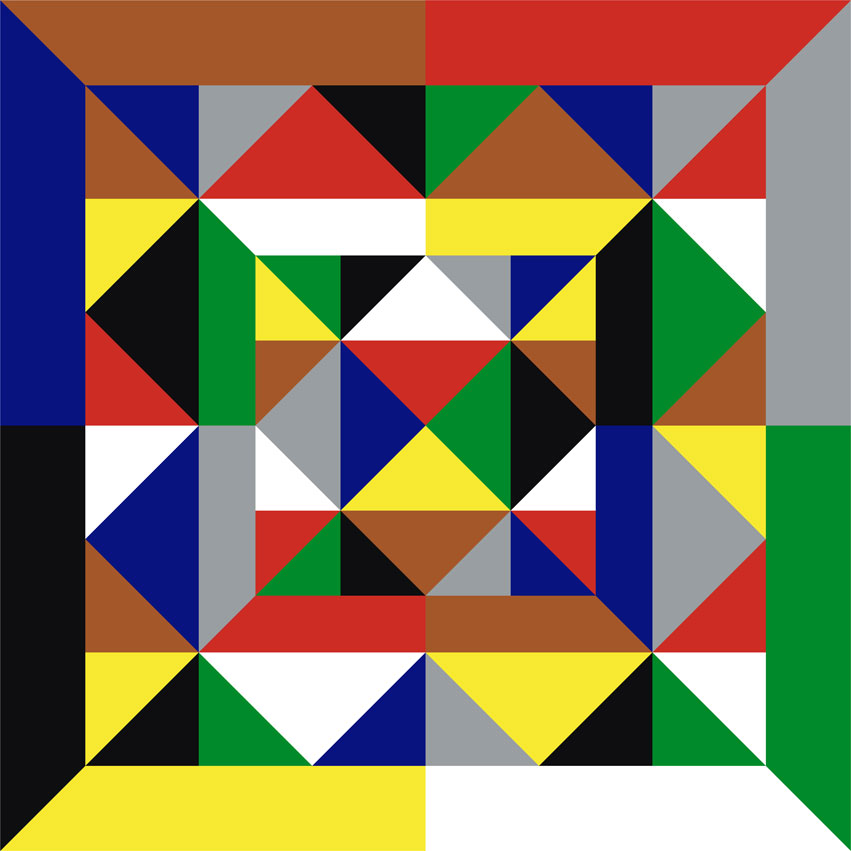

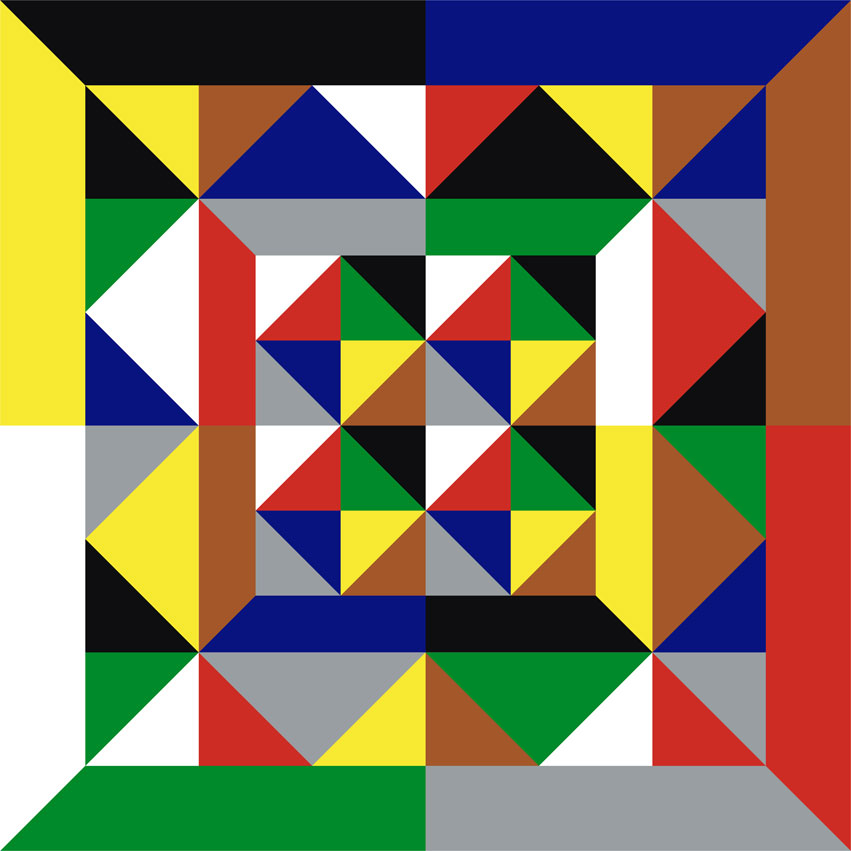

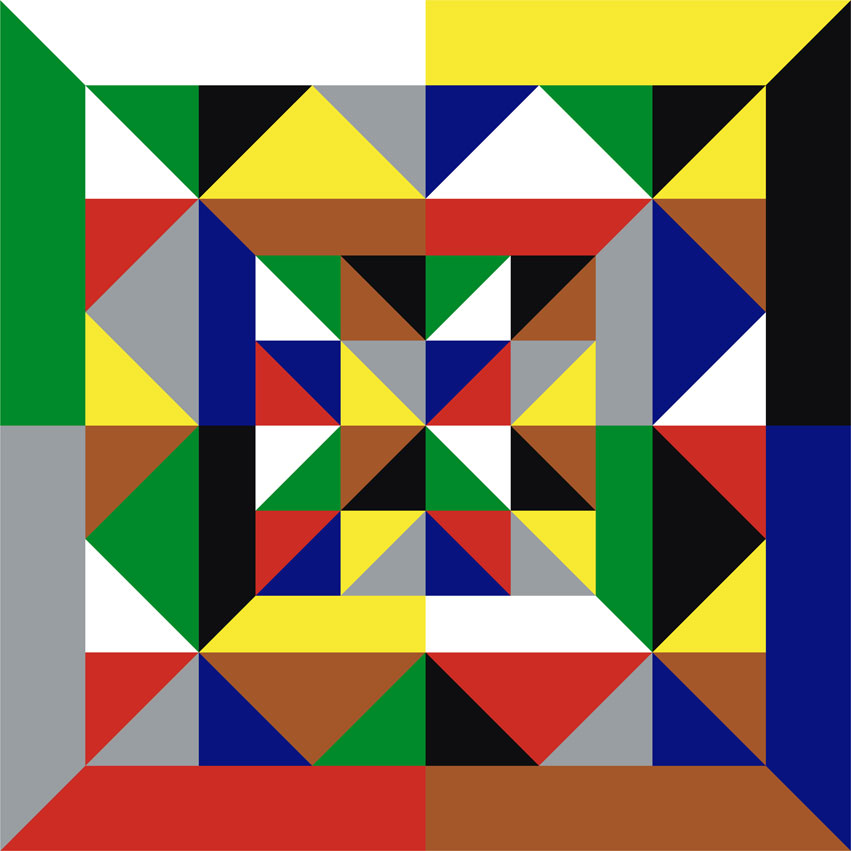

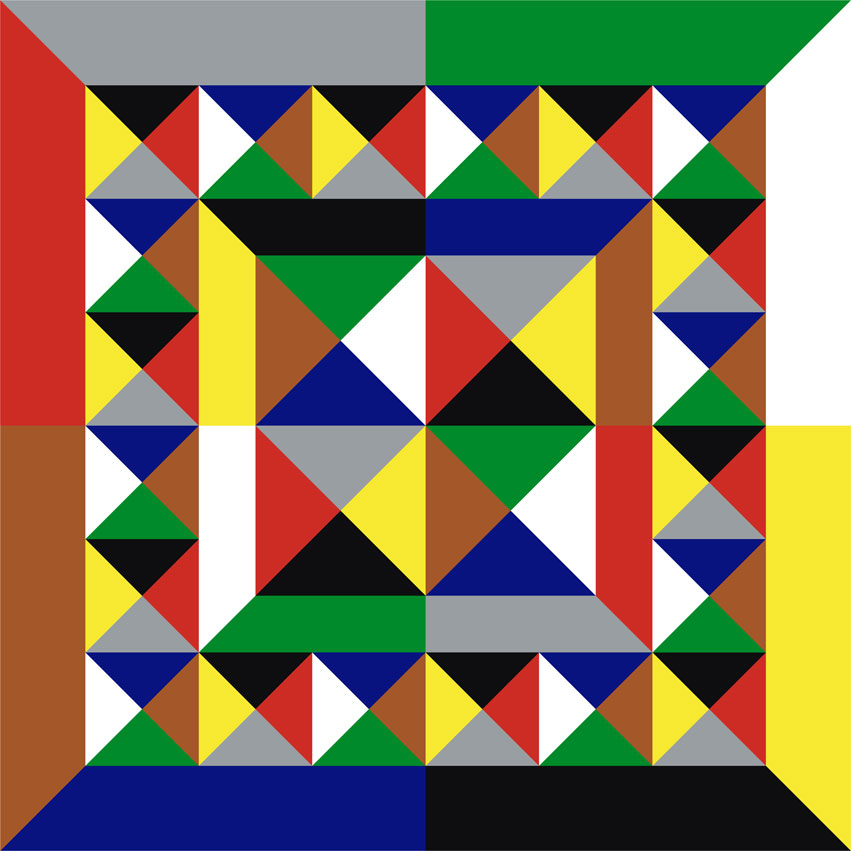

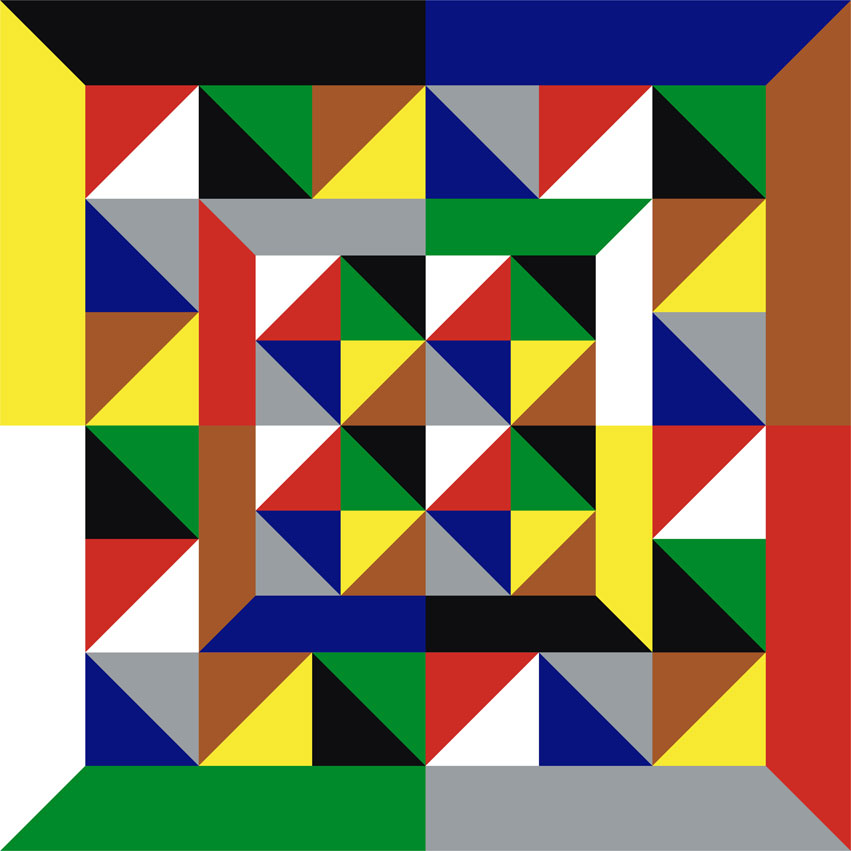

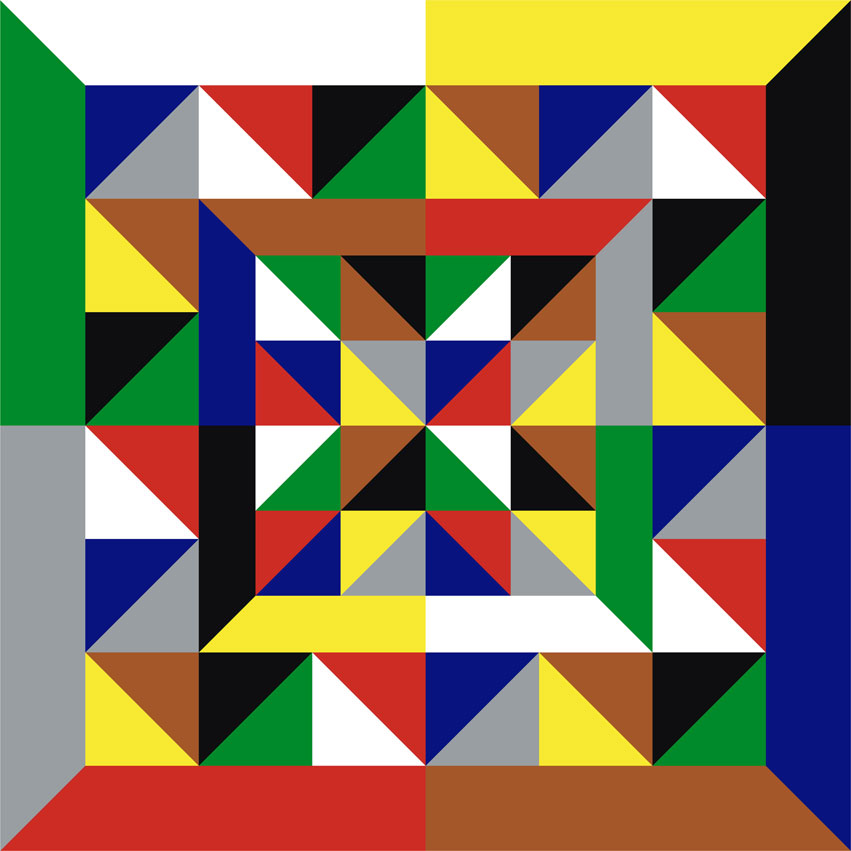

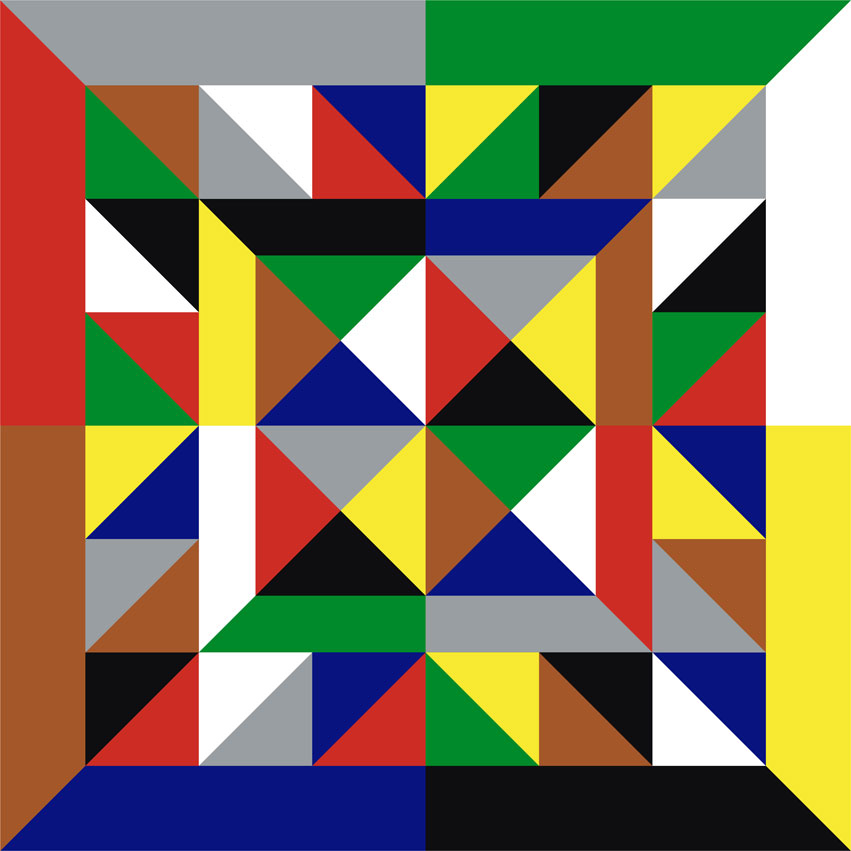

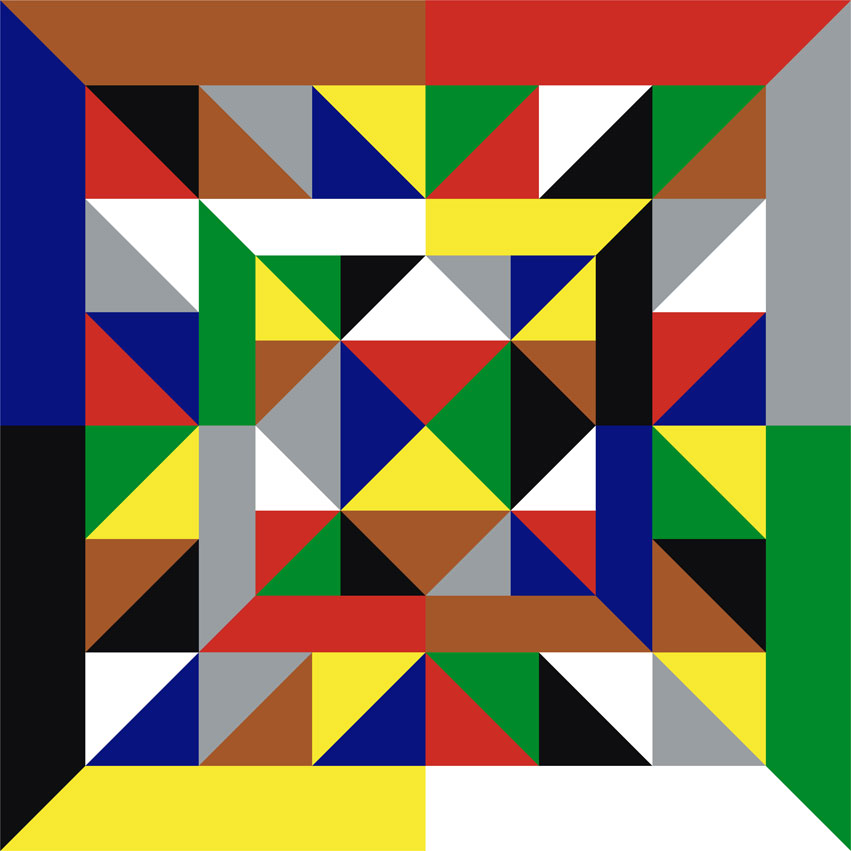

Dies vorausgeschickt, besteht die Grundidee der vorliegenden Arbeit im Erschaffen eines rein

abstrakten, mehrdimensionalen Bildraumes, indem ich den Gegenstand der Anschauung durch die

konkrete Wirklichkeit des Ornaments ersetzte.

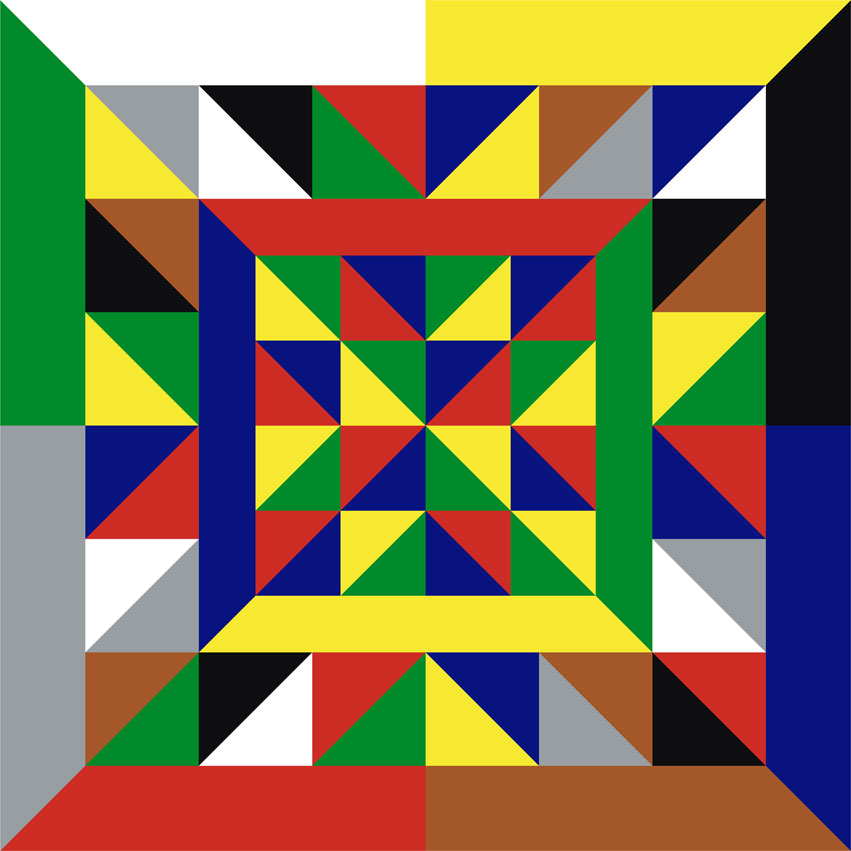

In den Gründerjahren der Abstraktion, bis in die 1950er Jahre hinein, war das Ornament als bloßes

Dekor verfehmt; Symmetrie und repetitive Struktur sollten um jeden Preis vermieden werden. Ein

Kunstwerk sollte sich deutlich von einer Tapete oder Tischdecke unterscheiden; weil es ja nicht zuletzt

einen weit höheren kulturellen Stellenwert beanspruchte.

Mit dem Durchbruch der Konzeptkunst, in den 1960er Jahren, wurde diese Unterscheidung hinfällig; die

Kunstverfassung eines Objekts war ohnehin nicht länger abhängig von dessen visuellen Qualitäten. Das

Kunstobjekt wurde als Stellvertretersymbol einer Idee begriffen. Unter dieser Voraussetzung konnte

auch das Ornament eine Trägerfunktion übernehmen, als eine Art Ready-made Struktur.

Die vorliegende Arbeit bleibt den Grundprinzipien der konzeptuellen Kunst, dh. dem Primat von Idee

über Optik, dem Vermeiden von Handschriftlichkeit, sowie einer generellen Rationalisierung des

kreativen Aktes, verpflichtet; was jedoch nicht bedeutet, daß visuelle Qualitäten negiert würden. Im

Gegenteil, ein Bild ist meiner Auffassung nach etwas, das vom Sehen her konzipiert ist.

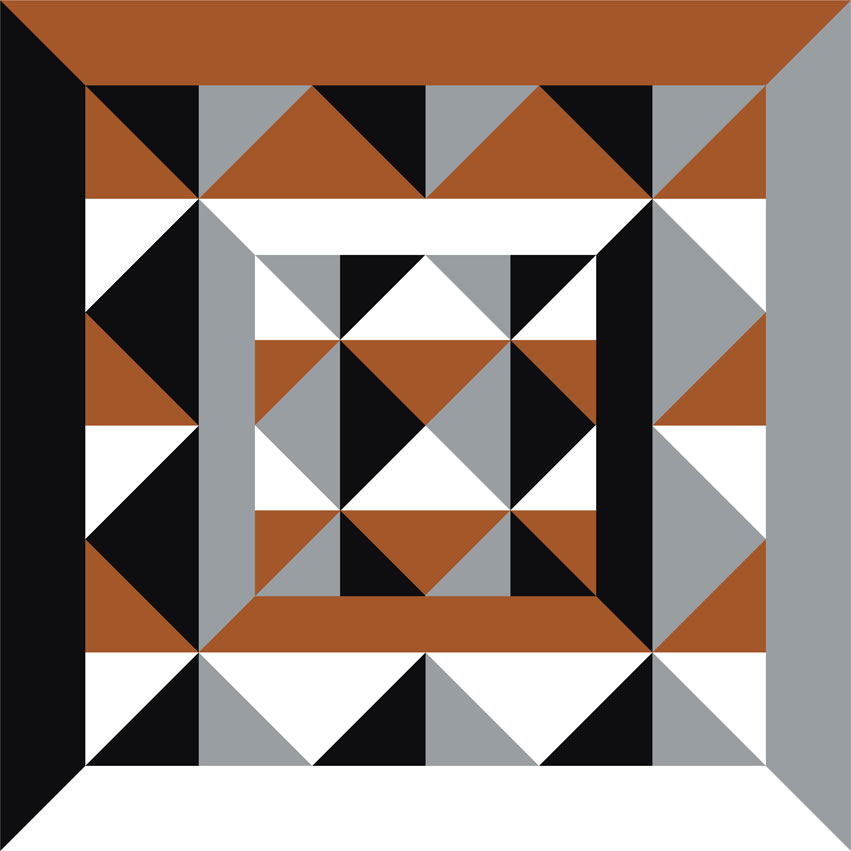

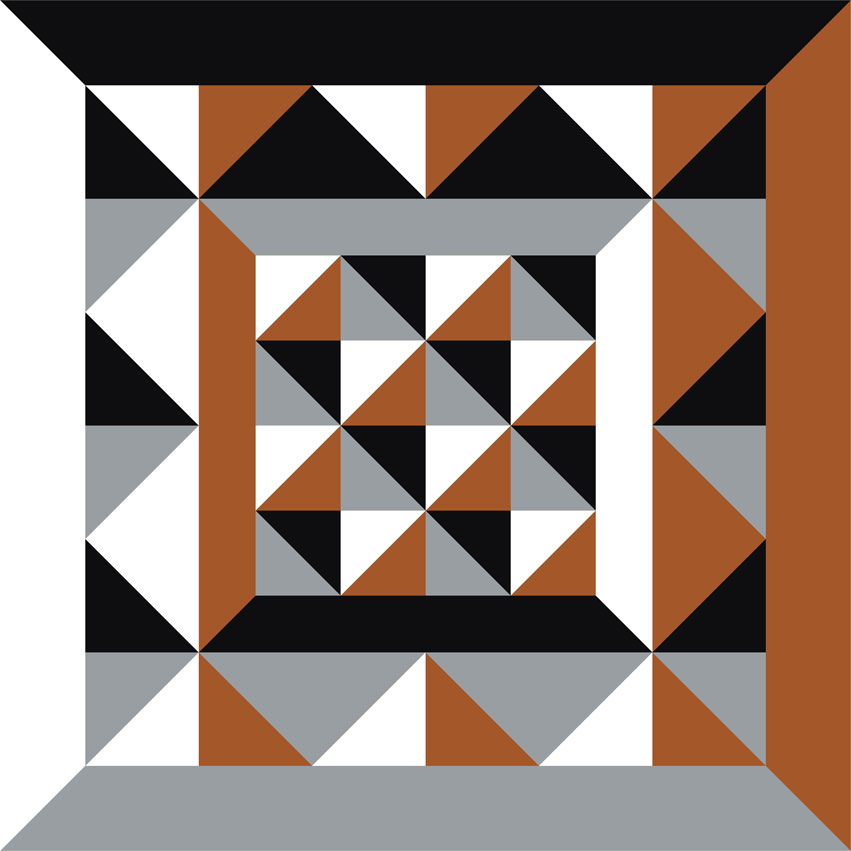

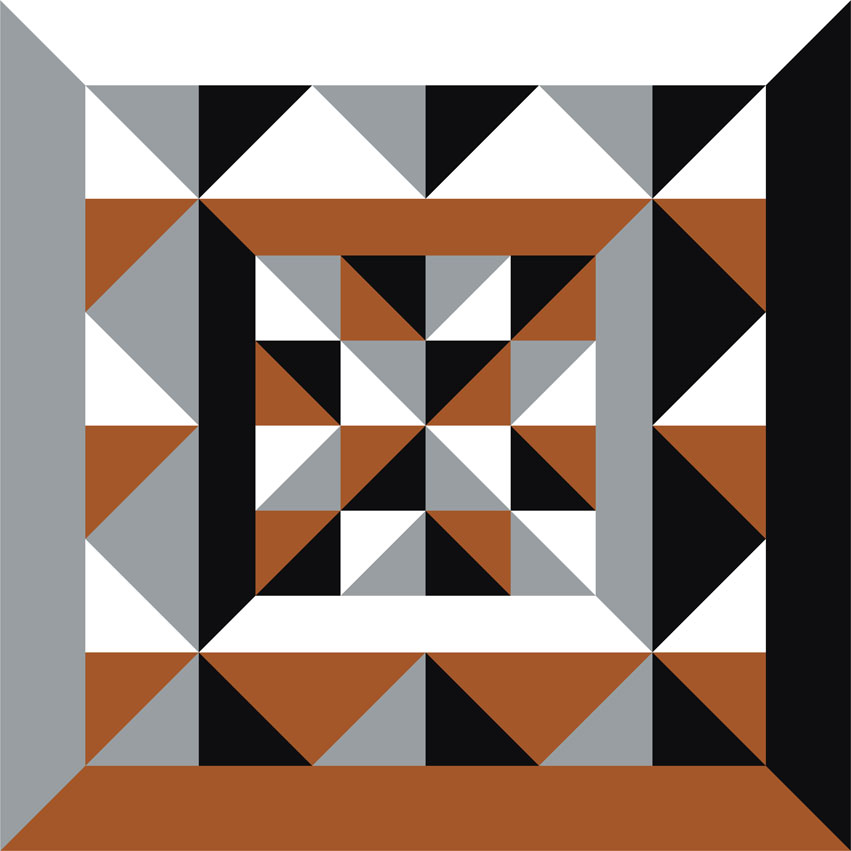

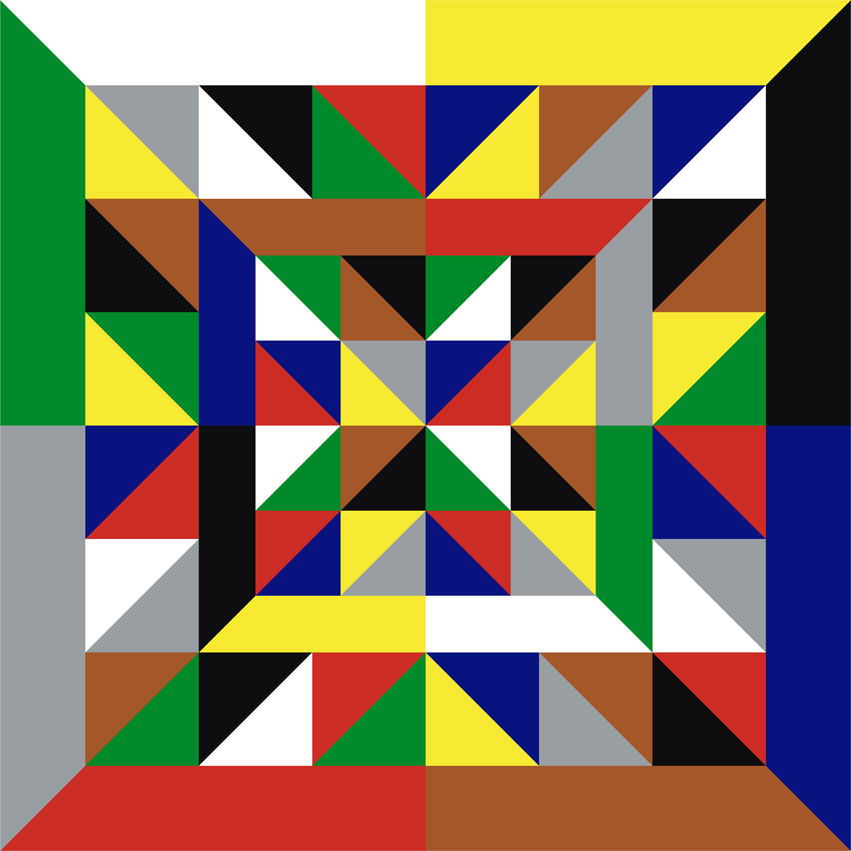

Was hier zu sehen ist, ist das Wirken formaler und farblicher Funktionen, die durch ein geometrisches

Ornament strukturiert werden. Für die Aufteilung der Fläche, in gleichschenklige Dreiecke, sowie die

Zusammenstellung und Verteilung der Farben, habe ich eine Formel entwickelt. Die Komposition beruht

auf einem Modulsystem, von je 4 äußeren und 4 inneren Komponenten; daraus ergeben sich insgesamt

16 Kombinationsmöglichkeiten. Jedes Modul ist in je 3 verschiedenen Farbsätzen ausgeführt, sodaß

jedes der 16 Bilder in je 9 verschiedenen Farbkombinationen vorkommt. Daraus resultiert die Summe

von 144, unterteilt in 9 Sequenzen, zu je 16 Bildern.

Die Komposition folgt der Grundregel, daß jede Farbe in exakt der gleichen Häufigkeit und Menge vorkommt; sowohl innerhalb des einzelnen Moduls, als auch der Serie als ganzer.

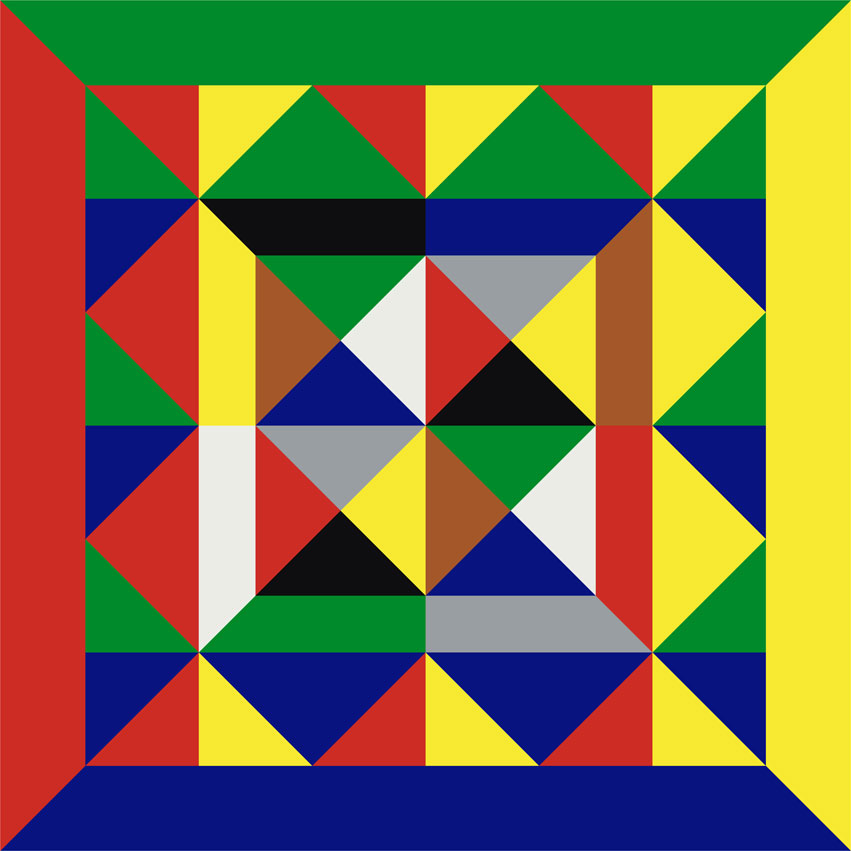

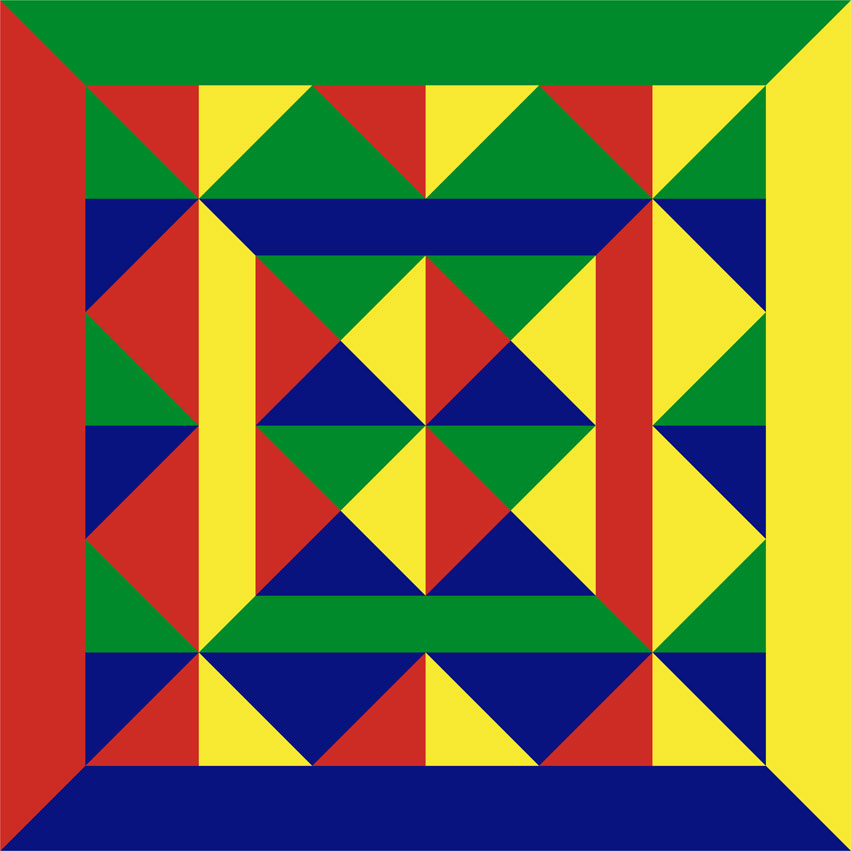

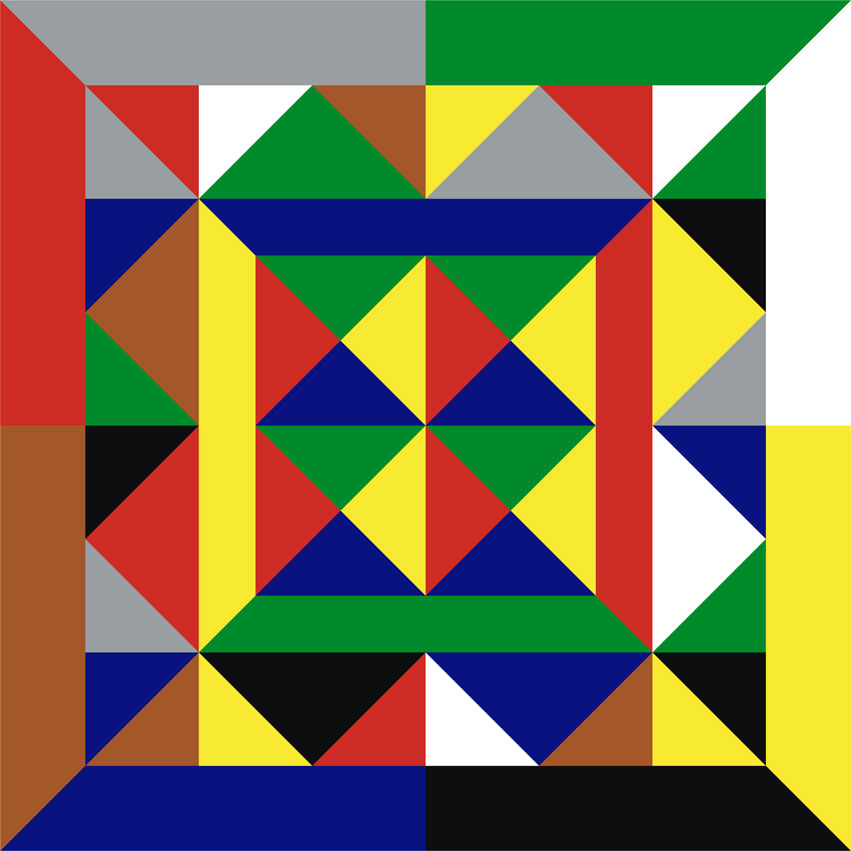

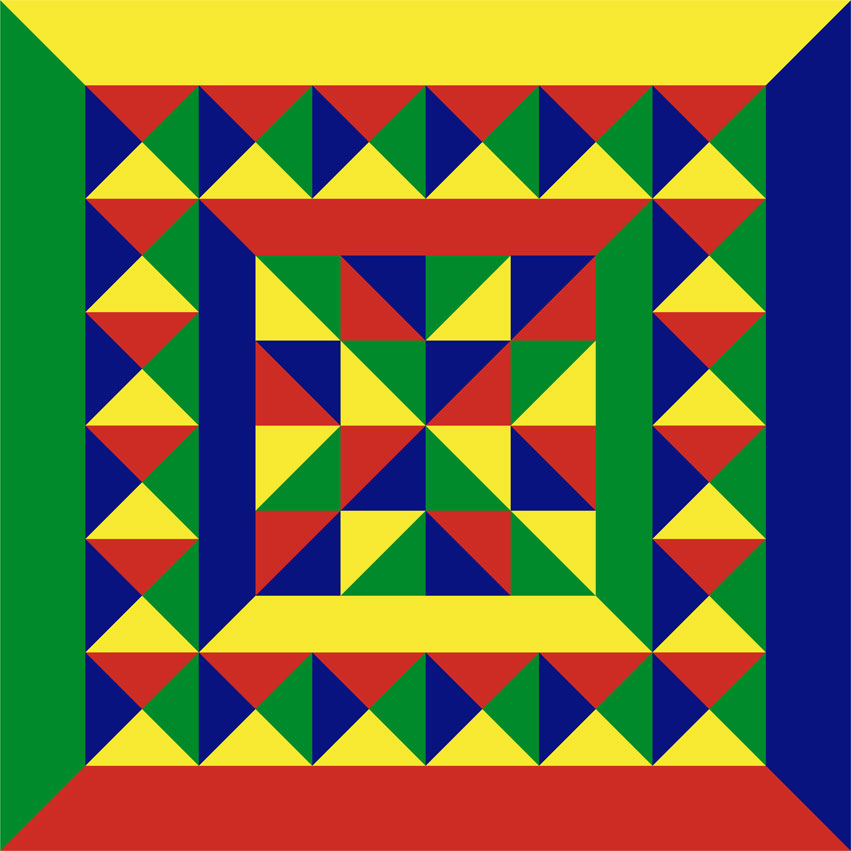

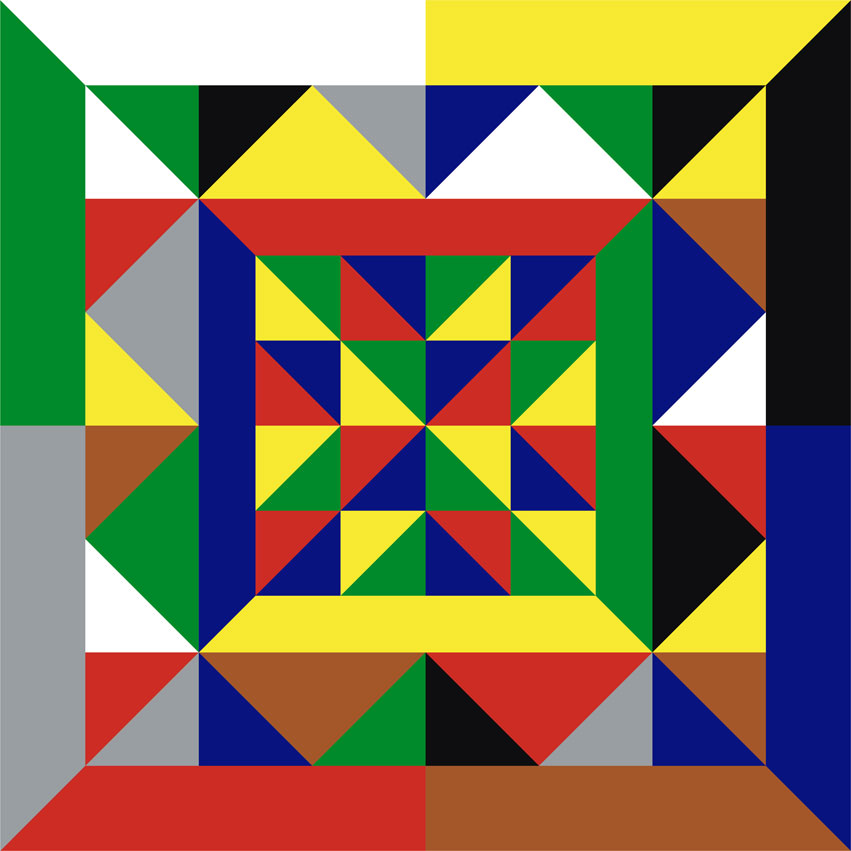

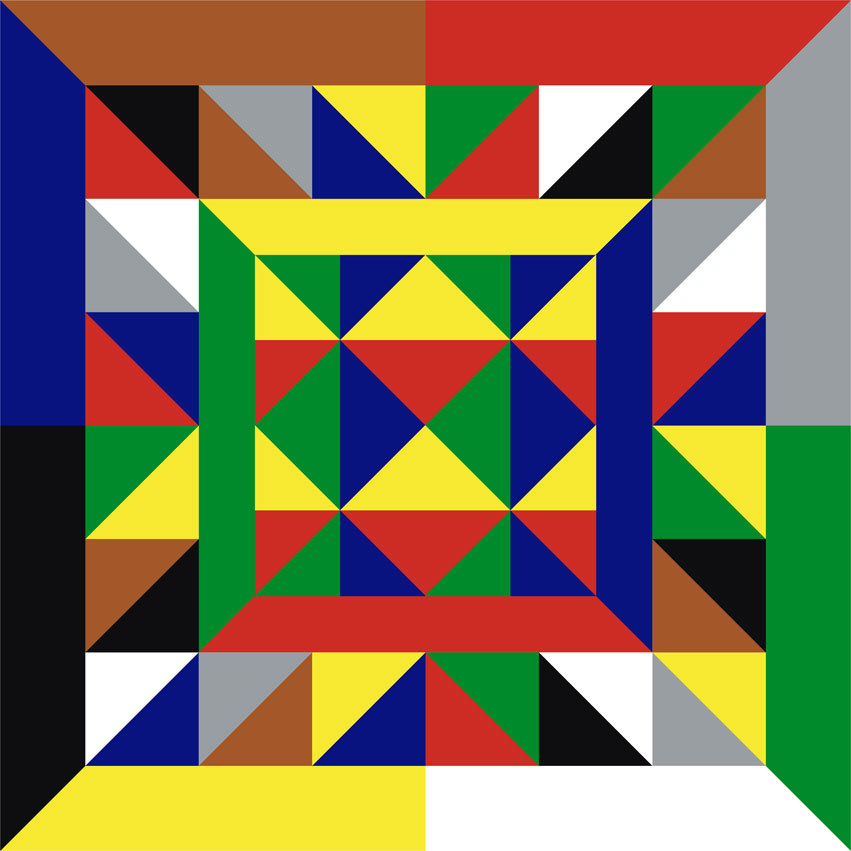

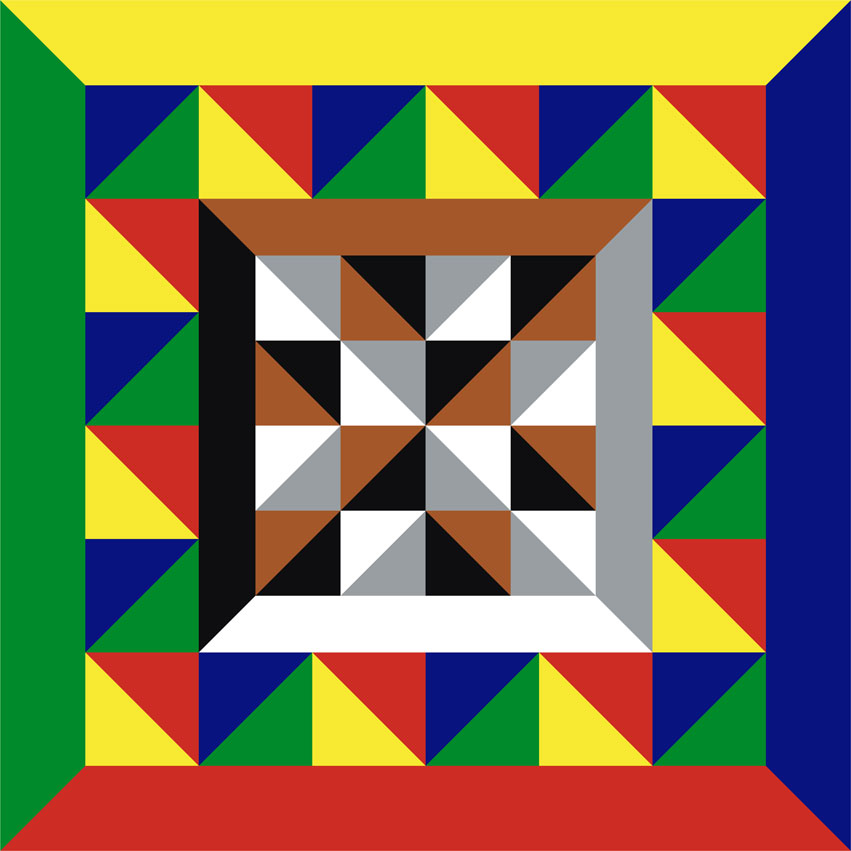

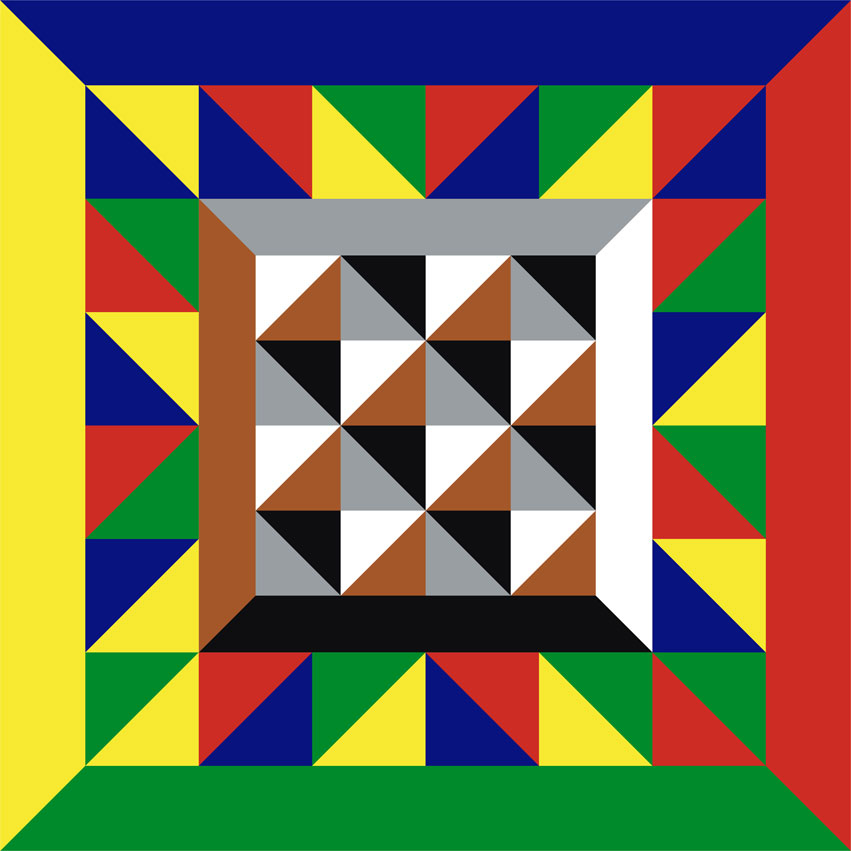

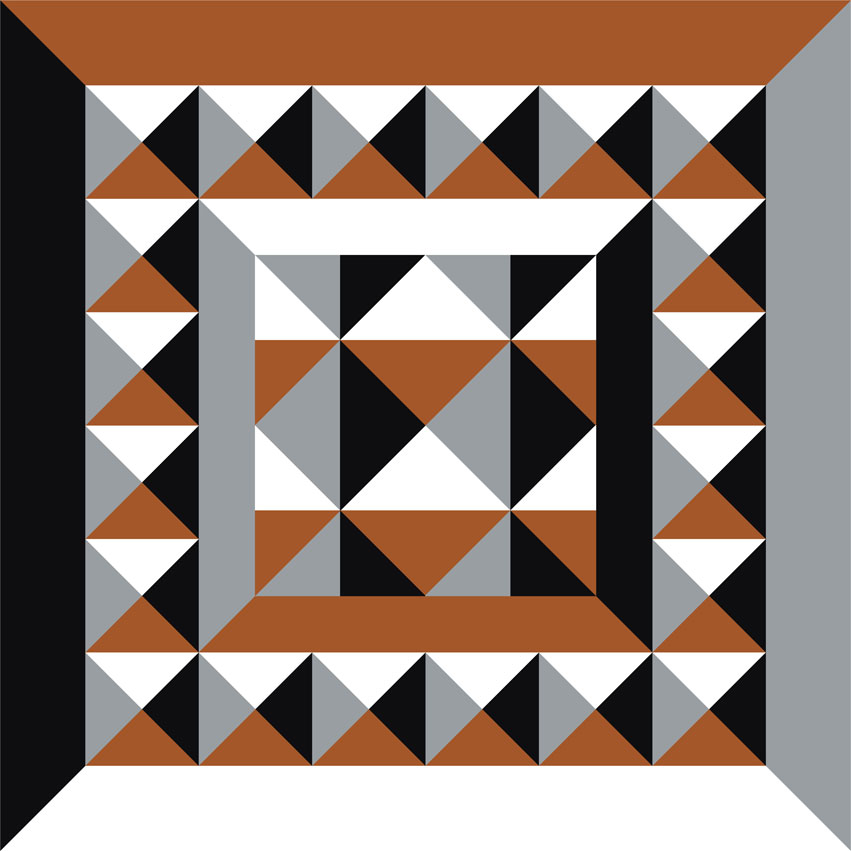

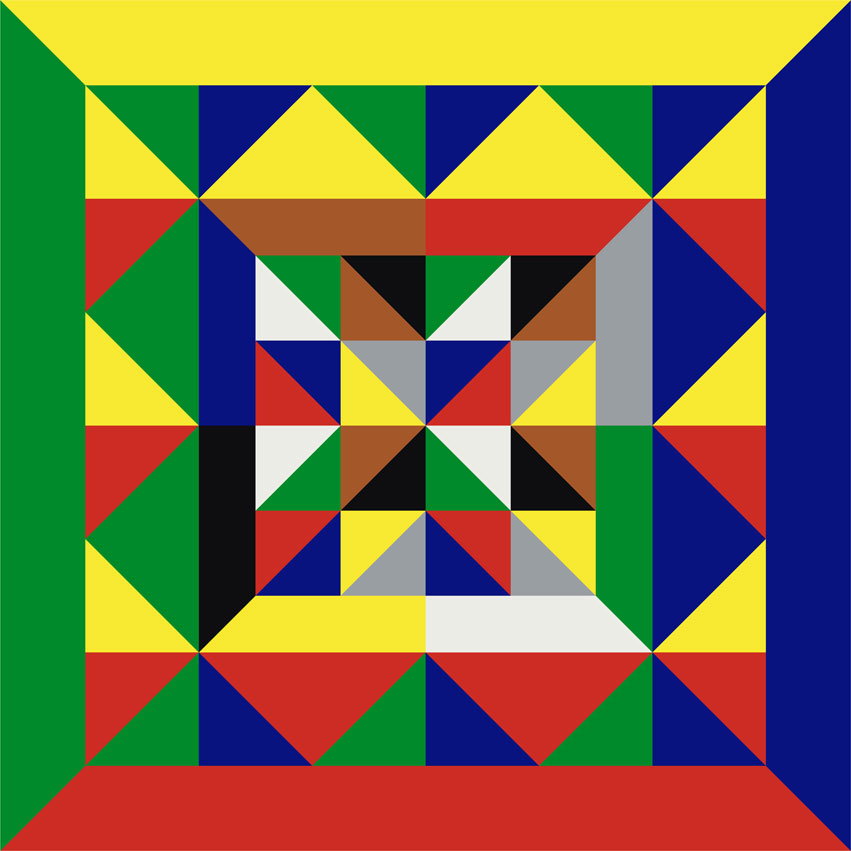

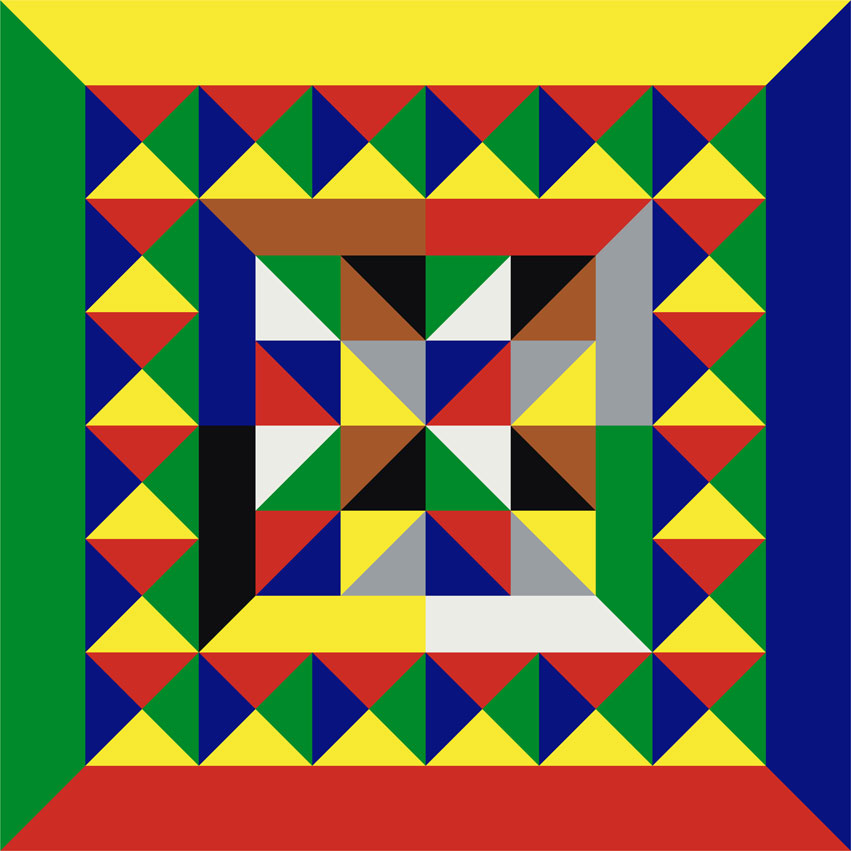

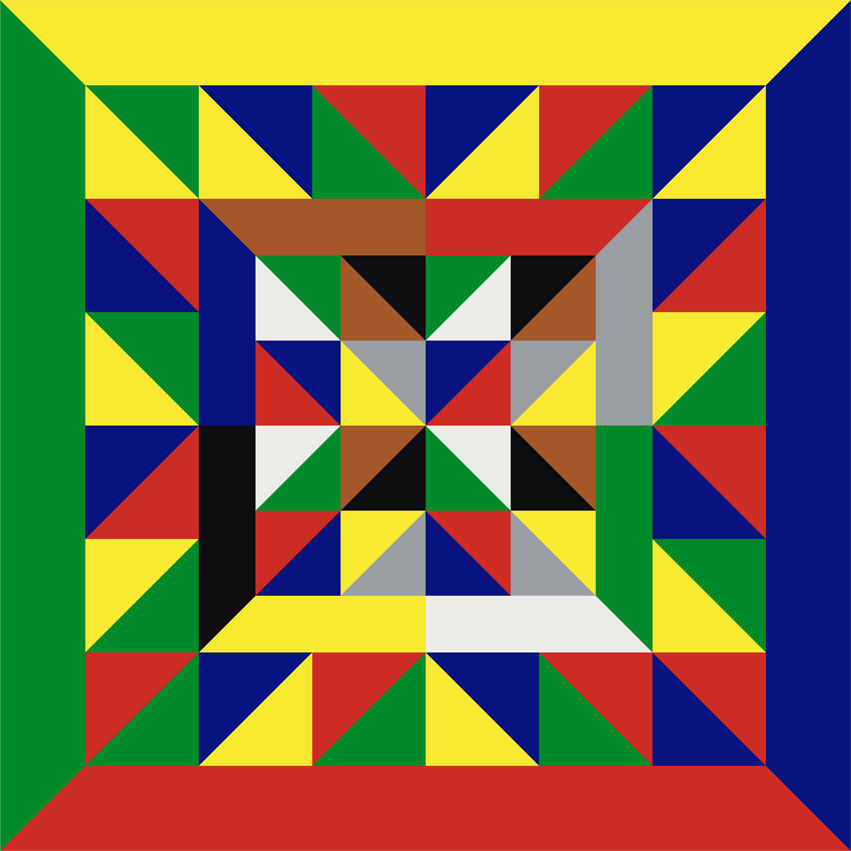

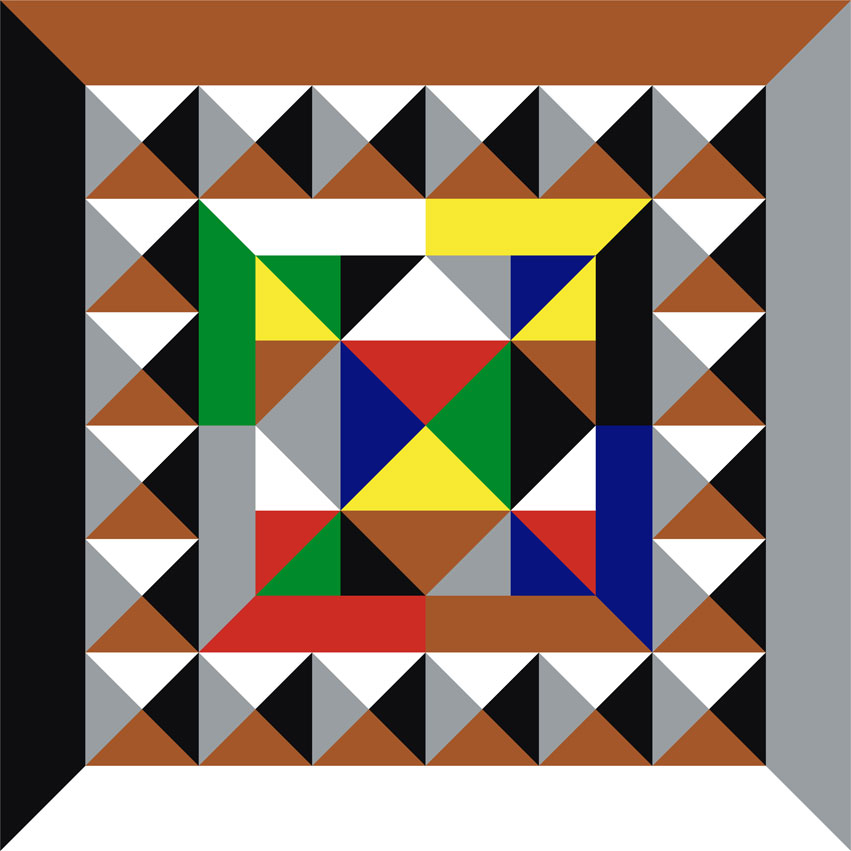

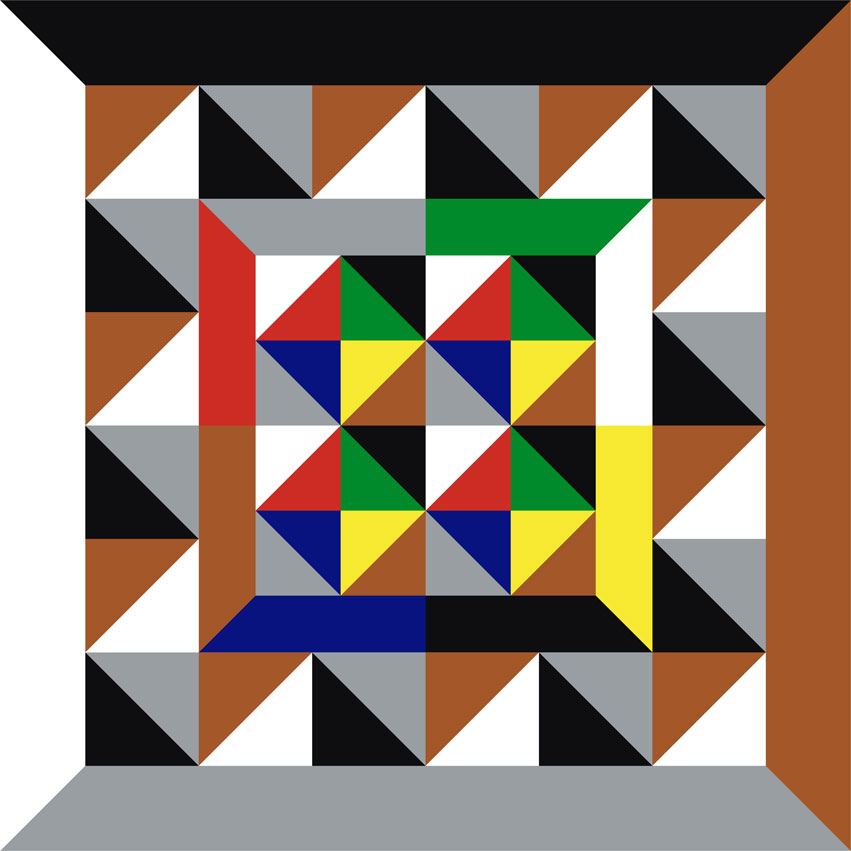

Durch das serielle Moment kommt ein Zeitfaktor ins Spiel. Die einzelnen Bilder reagieren miteinander;

die Farben und Muster ergänzen und überlagern sich, sowohl direkt, auf der Netzhaut, als auch indirekt,

im Gedächtnis des Betrachters. Je nach Reihenfolge, Abstand, und Dauer der Betrachtung, entstehen

immer neue Eindrücke.

Damit die beabsichtigte Wirkung sich einstellen kann, sollte jedes Bild mindestens 10 Sekunden lang

angeschaut werden.

The guideline of Constructivist painting was the avoidance of illusionistic spatial depth. In Cubism, on

the other hand, which marks a transitional stage between object-related and pure abstraction, three-

dimensionality is conserved to a certain extent; although not in a naturalistic sense. The Cubist space is

an irrational space, where an object is viewed from different perspectives simultaneously.

Depth of space in painting is created mainly by vanishing lines; a diagonal in the picture involuntarily

creates a 3D effect, even where it has a merely ornamental function. That is why the diagonal was

forbidden in Neo-Plasticist painting. For Cubism, on the other hand, it was an elementary stylistic device

in its function as an intersection between different picture planes.

For some reason, the Cubists never advanced to pure abstraction; as if reference to the thing-world

were a condition of the process. The abstract purists, on the other hand, never embraced the Cubist

conception of a multi-perspectival pictorial space; pure geometric abstraction remained committed to

the credo of flatness.

Having said this, the basic idea of the present work consists in the creation of a purely abstract,

multidimensional pictorial space by replacing the object of contemplation by the concrete reality of the

ornament.

In the founding years of abstraction, up to the 1950s, the ornament was misunderstood as mere

decoration; symmetry and repetitive structure were to be avoided at all costs. A work of art should be

clearly distinguishable from a wallpaper or tablecloth; because, after all, it claimed a far higher cultural

status.

In the founding years of abstraction, up to the 1950s, the ornament was rejected as a supposedly mere

decorative accessory; symmetry and repetitive structure were to be avoided at all costs. A work of art

should be clearly distinguishable from a wallpaper or tablecloth; because, after all, it claimed a far

higher cultural status.

With the breakthrough of conceptual art, in the 1960s, this distinction became obsolete; the art

condition of an object was no longer dependent on its visual qualities anyway. The art object was

understood as a wild card of an idea. Under this condition, even the ornament could take on a carrier

function, as a kind of readymade structure.

The present work remains committed to the basic principles of conceptual art, i.e. the primacy of idea

over optics, the avoidance of handwriting, as well as a general rationalization of the creative act; which

does not mean, however, that visual qualities are negated. On the contrary, in my opinion a picture is

something that is conceived from seeing.

What can be seen here is the action of formal and color functions, which are structured by a geometric

ornament. For the division of the surface, in isosceles triangles, as well as the selection and distribution

of the colors, I have developed a formula. The composition is based on a modular system, of 4 outer and

4 inner components each; this results in a total of 16 possible combinations. Each module is executed in

3 different color sets, so that each of the 16 images occurs in 9 different color combinations. This results

in a total of 144, divided into 9 sequences of 16 images each.

The composition follows the basic rule that each color occurs in exactly the same frequency and quantity; both within the individual module, as well as the series as a whole.Through

the serial moment, a time factor comes into play. The individual images react with each other; the colors

and patterns complement and overlap, both directly, on the retina, and indirectly, in the viewer's

memory. Depending on the sequence, distance, and duration of viewing, new impressions are always

created.

In order for the intended effect to occur, each image should be viewed for at least 10 seconds.